Planet bonanza! Refined technique for planet ID nearly doubles total.

New technique for sifting data from NASA's Kepler planet-hunting mission nearly doubles the number of confirmed planets so far. Of the new batch of 715, only four have certain Earth-like characteristics.

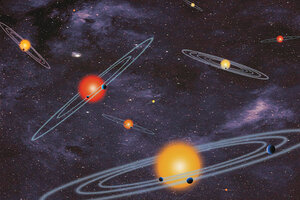

This handout of an artist's conception depicts multiple-transiting planet systems, or stars with more than one planet. NASA on Wednesday confirmed, in bulk, the existence of 715 additional planets circling stars other than our sun – thanks to data from the planet-hunting Kepler mission.

AP Photo/NASA

Astronomers have uncovered 715 previously unannounced planets after using a new technique for sifting through the first two years' worth of data from NASA's Kepler mission.

All are in systems with multiple planets. Only 6 percent of the planets are larger than Neptune, while four are between 2 and 2.5 times the size of Earth and orbit within the habitable zone of their host stars.

The discoveries, unveiled en masse at a briefing on Wednesday, vault Kepler's planet-hunting approach to the head of the list of most-productive detection methods. Kepler hunted for planets by looking for the slight dimming in a star's light as one or more of its planets eclipse it with each orbit.

With one analytical sweep, the team has nearly doubled the number of confirmed extrasolar planets, the researchers say.

Wednesday's announcement is likely to prompt astronomers to take a harder look at their explanations for planet formation.

"Many of these are crazy systems," said Sara Seager, an astronomer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. Many of them are very compact, with a few to several planets falling within what would be Venus's orbit, while others host multiple planets that orbit their stars within what would be Mercury's orbit.

Moreover, many of the new planets range in sizes that fall between the sizes of Earth and Neptune – a range missing from our solar system.

"We don't really know their composition or how they came to exist," Dr. Seager said.

NASA launched Kepler in March 2009 with the aim of surveying more than 150,000 stars simultaneously for signs of planets. The goal was to provide a census of extrasolar planets, with a particular focus on finding planets with Earth's size and mass orbiting around a sunlike star at Earth's distance.

The observation stage of the mission ended last May after the craft developed problems with its attitude-control system. This compromised Kepler's ability to point itself with the level of precision needed to make its measurements of the subtle, regular wink in starlight that would herald an orbiting planet.

Until now, the team has been cautious about claiming discoveries of planets unless a planet's presence is confirmed by an independent approach using large ground-based telescopes. That still holds true for single-planet systems.

But with multiplanet systems, the team has found strength in numbers when declaring objects are planets.

Out of 150,000 stars Kepler observed, just under 4,000 have been identified so far as hosting planets. More than 10 percent of these hosts show evidence for more than one transiting object, many with orbital periods similar to our solar system's inner planets or shorter.

If the transiting objects were stars, these systems would be highly unstable. The objects would be orbiting too close together and too close to their host star. Their gravitational interactions would quickly fling them apart, explained Jack Lissauer, a researcher at NASA's Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, Calif., and the lead author of a paper describing the approach.

Based on these observations, the team devised a set of 10 tests transiting objects must pass to earn the title of planet.

Kepler researchers applied the approach to 305 stars that showed evidence of more than one transiting planet candidate. Out popped 715 planets.

It's an approach that has allowed the Kepler team to "strike the Mother Lode" that yields "a veritable exoplanet bonanza," Dr. Lissauer said.

The ever larger number of small planets Kepler's data are revealing also is vital for continued efforts to hunt for planets with space-based telescopes, Seager added.

"Having 'candidates' just doesn't cut it" when it comes to proposing new telescopes designed to directly image extrasolar planets, adds Seager, who was not part of the team reporting the results but who is working on such telescopes.

"We need to be reassured that small planets are common," she said, noting that these latest results reinforce the idea that Kepler has excelled in providing that reassurance. "Nature wants to make small planets."