NASA mission to Europa takes small step toward reality

NASA's 2015 budget includes a small down payment on a potential mission to Europa, a moon of Jupiter and one of the solar system's potentially most habitable spots.

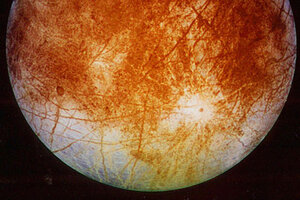

This image of Jupiter's ice-covered moon, Europa, was taken by the Galileo spacecraft. NASA said Tuesday it is making preparations to plan a robotic mission to Europa.

Jet Propulsion Laboratory/NASA/AP/File

Europa or bust?

In its fiscal 2015 budget, NASA has included a small deposit on a possible mission to one of the solar system's potentially most habitable spots: Jupiter's ice-sheathed moon Europa.

The agency is asking Congress for $15 million to officially begin identifying affordable concepts for a Europa mission, noted Elizabeth Robinson, NASA's chief financial officer, at a briefing on Tuesday.

At the moment, the agency has no official cost estimate for such a mission and a launch date no more specific than sometime in the mid-2020s. But a 2012 study commissioned by NASA highlighted three approaches that carried price tags ranging from $1.8 billion to $3 billion. Of those, the study team identified a $2.1 billion mission as the one that would return the most science for the best price. It consisted of a spacecraft performing multiple flybys of Europa.

While $15 million may seem like chump change against a potential price tag of $2 billion, give or take, putting the figure in the budget "is significant, it means we're getting serious," says James Green, who heads NASA's planetary science division.

Congress has already delivered $80 million to NASA to begin spadework on a mission to Europa in mind. Now, by putting the mission in the budget, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is giving the program a new level of concreteness, since it must include spending estimates for an additional four years beyond fiscal 2015.

"The fact that OMB put it in as line item by name says that administration finally got the message that Congress was going to insist on this and they might as well go ahead and put it in the budget," says Scott Hubbard, former head of NASA's Mars exploration program and now a consulting professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif.

To his way of thinking, he says, $15 million is a bit low for starting on a mission that already has a viable concept option – the so-called Europa Clipper, which involves repeated flybys by a craft in a highly eccentric orbit. But the added political gravitas is not insignificant.

Europa has captured the imaginations of space scientists, astrobiologists, and science-fiction writers alike. NASA's Galileo mission to Jupiter showed that craters on Europa's icy surface were sparse. Instead, vast regions were covered with features that resembled those seen in sea ice on Earth. These pointed to movement in the crust driven by the circulation of a subsurface ocean of water or slush. Tidal heating from the moon's gravitational interaction with Jupiter is thought to keep the subsurface ocean liquid and perhaps provide energy for geothermal activity on the ocean bottom.

But the chaotic surface and signs of resurfacing Galileo observed could be relatively old. It was unclear if these processes were still active.

Then last December, researchers revealed evidence for water vapor above the surface of the moon's South Pole. The data, gathered by the Hubble Space Telescope, suggested that the moon is active today. Although the source of the water vapor is uncertain, the team reporting the discovery noted that an eruption of subsurface water was the most likely explanation.

A mission to Europa has been a high priority for planetary scientists for a decade. But recent support has been guarded. In 2011, a panel of planetary scientists convened by the National Research Council set out research priorities for the 2013-2022 decade. The exercise was tempered by the push in Washington to reduce federal deficits.

The priorities included three so-called flagship missions, one of which was a mission to Europa. At the time, such a mission carried an estimated price tag of $4.7 billion. If the costs for the Europa mission, plus the No. 1 choice for a flagship – an astrobiology mission to Mars that included caching samples for later return – proved too high, the panel was willing to see both scrapped to avoid deep cuts in high priority mission in other categories.

While previous mission concepts for Europa may serve as useful starting points, a final mission is likely to be shaped by the discovery that the under-ice ocean is communicating directly with the surface, Dr. Green says, adding: "That shattered everything."

The $15 million is designed to be used help researchers to come up with a mission that can take advantage of the discovery in ways previous concepts could not.

This so-called pre-formulation stage "enables us to think differently about what would be on the spacecraft and how the spacecraft could make measurements," Green says. "This is really an active world. It punches 'reset' in the way we're thinking about it."