US fisheries laying waste to marine life, says report

The ocean conservation group Oceana says that between 17 and 22 percent of US catch is tossed back into the sea.

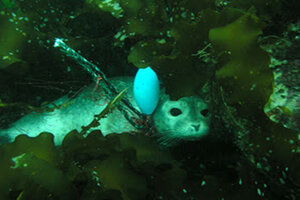

During fishing hundreds of marine creatures such as, dolphins, whales, sharks, sea birds, sea turtles get entangled in the fishing nets. Here you can see an entangled seal pup.

Steve Whitford 2004/Marine Photobank

The seafood on your plate apparently comes at a steep cost: the lives of countless dolphins, sea turtles, and whales.

According to a report by Oceana, an ocean conversation group, billions of pounds of 'bycatch' is thrown back into the sea every year by the US alone. [Editor's note: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this paragraph misstated the poundage.]

The report also lists nine "dirtiest" fisheries in the country that in total account for more than half of all reported bycatch in the US.

"Bycatch is the catch of non-target fish and ocean wildlife, including what is brought to port and what is thrown overboard at sea, dead or dying," says Oceana.

"While bycatch data is often outdated and inaccurate, researchers estimate that 17-22 percent of U.S. catch is discarded every year, according to the best available data. Bycatch in the U.S. could amount to 2 billion pounds every year, equivalent to the entire annual catch of many other fishing nations around the world," the report says.

The world estimates are even more staggering: 63 billion pounds of bycatch annually, most of which is thrown back into the sea. Basically, bycatch, said Oceana campaign director Dominique Cano-Stocco could be just about any marine animal that gets trapped in the fishing nets along with those that fishermen are actually looking for.

“Whether it’s the thousands of sea turtles that are caught to bring you shrimp or the millions of pounds of cod and halibut that are thrown overboard after fishermen have reached their quota, bycatch is a waste of our ocean’s resources. Bycatch also represents a real economic loss when one fisherman trashes another fisherman’s catch," Cano-Stocco said in a press release.

In the groundfishing industry, fishermen cannot be selective about their targets, because there are certain kind of fish that are found together in the sea, says Angela Sanfilippo, executive director of the Massachusetts Fishermen’s Partnership. For instance, a haddock, a pollock, and a flounder can be trapped together.

Another problem are the caps that prohibit fishermen to catch fish beyond a certain number. The rest have to be discarded, she says. Also, customers want to buy certain kind of fishes. They don't have the knowledge basically and therefore, they do not realize that almost all fish found in the ocean are good protein sources, she says.

Catch can also be wasted because of a limited boat size. But much of the bycatch problem arises from the way in which fish are caught, says Amanda Keledjian, a marine scientist at Oceana and the author of the report.

"It’s no wonder that bycatch is such a significant problem, with trawls as wide as football fields, longlines extending up to 50 miles with thousands of baited hooks and gillnets up to two miles long," she says.

Using selective fishing gear, such as harpoons instead of gillnets or equipping turtle excluder devices in fishing nets can help in preventing bycatch while fishing, Dr. Keledjian told the Monitor.

The Southeast Shrimp Trawl Fishery alone kills 50,000 sea turtles every year, Keledjian adds.

In various parts of the country, efforts are underway to save sea turtles by banning certain fishing nets.

"Drift nets are California's deadliest catch," said Teri Shore, program director at the Turtle Island Restoration Network told Santa Cruz Sentinel "They're curtains of death."

Some California state legislators are seeking to ban these nets. "The fact that California still permits the use of these deadly drift gillnets while states on the Western Coast has banned the use is shameful, " the bill's lead author, Assemblyman Paul Fong (D-San Jose,) told the Sentinel.