Moon orbiter LADEE crashes triumphantly after 'amazing' mission

After completing all of its goals and then some, NASA's LADEE orbiter took increasingly daring passes, skimming closer and closer to the moon surface, ultimately crashing just days before it would have run out of fuel.

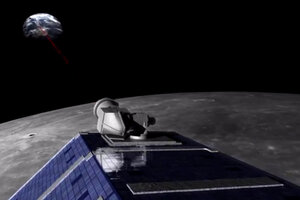

Artist concept of NASA's Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE) using its Lunar Laser Communications Demonstration (LLCD).

NASA

LADEE did not "go gentle into that good night."

The vending-machine-sized orbiter ended its mission to the moon by smashing into the lunar surface during a deliberately planned, high-risk maneuver sometime between 9:30 and 10:22 p.m. PDT on Thursday, April 17, NASA officials confirmed.

"We were less than a kilometer above the surface. Amazing!" says Sarah Noble, program scientist for the Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer. "No spacecraft has ever done that before."

When it crashed into a crater wall, "LADEE was traveling at a speed of 3,600 miles per hour – about three times the speed of a high-powered rifle bullet," said Rick Elphic, LADEE project scientist, in a press release. "There’s nothing gentle about impact at these speeds – it’s just a question of whether LADEE made a localized craterlet on a hillside or scattered debris across a flat area."

LADEE's mission to find electrified dust and "hopping" water molecules had always had an expiration date. Designed to last just 100 days in orbit, LADEE performed so well, and used fuel so efficiently, that it was able to eke out an extra month of observations after its nominal mission ended in early March.

"It was all serendipitous. We had no plan, when we launched, to have any kind of extended mission," Dr. Noble tells The Christian Science Monitor. "But we did better than expected on the launch, and all of our fuel margins turned out to be better than we expected, so we ended up with plenty of extra fuel. We ended up with 140 days of science, instead of 100 days of science."

Throughout its mission, LADEE flew in elliptical orbits, aiming the lowest part of each pass at the sunrise terminator. During its first 100 days, its closest approach came 25 to 30 miles above the moon's surface, which was already much closer than any other orbiting satellite. In the final 40 days, LADEE's operators let it fly it closer and closer to the ground, coming dangerously close to the hills and hummocks of the moon's heavily cratered surface in order to take unprecedented measurements.

In its last week, LADEE got within two miles of the surface, then within one mile of the surface. For comparison, commercial jets fly about six miles above the surface of Earth.

"We were in the 4 to 5 kilometer (2 to 3 mile) passes for most of the extended mission phase, but during the low passes last night, we got down to a few hundred meters," says Butler Hine, LADEE project manager at Ames. "We started clearing things around 1.7 km (1 mile), then down to 1.3 (4000 feet), then 800 meters (half a mile), then the pass before our impact pass, we were down around 300 meters (1000 feet). We got great science data."

Two of the three instruments on LADEE take "in-situ" measurements, examining gas molecules and dust particles as LADEE flies through them, so these final passes offered unprecedented information about the moon's near-surface environment.

The calculated risk paid off huge science dividends, says Dr. Elphic. "We're seeing things we hadn't seen before, at the higher altitudes," he tells the Monitor. "Science will definitely, definitely benefit from this risky, low-altitude extended mission."

They couldn't have performed such risky maneuvers during their nominal, 100-day mission, but after they had accomplished all of NASA's goals, they were given a freer rein. "The team essentially took a vote and decided that what they wanted to do was get as close as they could to the moon," says Noble. "The operators were very concerned: 'You understand, if we do this, we might go in early,' " she remembers them saying. ("Go in" is NASA-speak for "Crash into the surface.")

The science team responded, " 'We understand. We don't care. We want this data!' And it totally was worth the risk. We have some fantastic data," she says.

At the tail end of the mission, LADEE was confronted with a total lunar eclipse, which drained its solar-powered batteries and heaters as the little craft, like the moon it orbited, passed through Earth's deep shadow for four long, cold hours. LADEE was not designed to survive so long without solar power, and in fact its launch window had been selected to make sure the mission was over before the eclipse – but the little orbiter that could had outlasted everyone's expectations.

"The engineers were fantastic," Noble told the Monitor. "They tell us, 'There's no way you can survive that eclipse. We're not designed to survive it, you're not going to survive the eclipse, don't even think about surviving the eclipse.' And then when we get there, they say, 'Well, when we said you couldn't survive, what we meant was, we can't 100 percent guarantee it.' "

Once again, LADEE defied the odds. When it emerged from Earth's shadow, the heaters and batteries powered back up and kept LADEE going for a few more science-filled days before its final daring pass sealed its fate.

During impact, engineers believe the small spacecraft broke apart, heating up several hundred degrees – or even vaporizing – at the surface. Any material that remained is likely buried in shallow craters. NASA mission controllers are still working to determine the exact time and location of LADEE's final impact. With luck, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter will photograph the impact site.

"It's bittersweet, knowing we have received the final transmission from the LADEE spacecraft," says Dr. Hine of Ames. LADEE was built in-house at Ames, and its instruments "stayed in constant contact as it circled the moon for the last several months," he said. In addition to the lunar observations it sent scientists, LADEE communicated with the general public through tweets, like this one sent a few weeks ago:

LADEE's journey began on Sept. 6, when it launched (along with a photobombing frog) from the Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia. LADEE reached the moon Oct. 6 and began gathering science data on Nov. 10. It completed its primary mission on March 1, then began its serendipitous extended mission. If it had survived Thursday's kamikaze run, it would have completely run out of fuel and coasted to a crash-landing sometime Monday.

LADEE measured the moon's almost non-existent atmosphere – technically, the "surface boundary exosphere" – and looked for evidence of a lunar water cycle. In addition, scientists are analyzing LADEE's data in hopes of solving a long-standing mystery: What caused the pre-sunrise glow seen above the lunar horizon on several Apollo missions? LADEE also carried an experiment in two-way communication via laser, instead of the standard radio waves. The Lunar Laser Communication Demonstration successfully transmitted data over the 239,000 miles from the moon to the Earth at a record-breaking download rate of 622 megabits-per-second (Mbps) and from the Earth to the moon with an error-free data upload rate of 20 Mbps.

"LADEE was a mission of firsts, achieving yet another first by successfully flying more than 100 orbits at extremely low altitudes," said Joan Salute, a LADEE program executive. "Although a risky decision, we're already seeing evidence that the risk was worth taking.”