Scientists glimpse 'magic island' on Saturn's largest moon

A feature in a northern sea on Titan appeared suddenly before disappearing again. Researchers attribute this phenomenon to the shifting seasons on Saturn's moon.

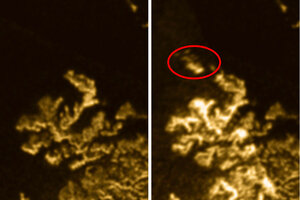

Right: Region of the transient features before they were discovered. Transient features are not present. This image was acquired by the Cassini RADAR system on April 26th, 2007.

Left: Transient features in Ligeia Mare, circled in red. This image was acquired by the Cassini RADAR system on July 10th, 2013.

Both images were modified for aesthetic appeal and are shown in false colour.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/Cornell

Aristotle believed that the bodies in our solar system were unchanging spheres, eternally the same. He couldn't have been more wrong.

In 2013, a feature on Saturn's largest moon, Titan, suddenly appeared. And then, just as suddenly, it vanished.

Where there appeared to be nothing more than ocean, researchers discovered a "magic island" in Titan's northern sea.

Officially called a "transient feature," the scientists called it "magic" because it appeared seemingly out of nowhere.

They came upon this unexpected feature while examining data from NASA's Cassini spacecraft, which has been orbiting Saturn since 2004. When comparing data taken by Cassini over the course of several months, they spotted a bright feature in one frame that didn't exist in the others.

Cassini had previously revealed evidence of seasons on Titan, observing how added sunlight caused shorelines to shift in the moon's southern hemisphere. But the same influence had not been seen on Titan's northern half, until July 2013, when the spacecraft spotted the island-like feature in Titan's northern sea, Ligeia Mare.

"This discovery tells us that the liquids in Titan's northern hemisphere are not simply stagnant and unchanging, but rather that changes do occur," said the study's lead author, Jason Hofgartner, a graduate student at Cornell University, in a news release.

This "island" is not actually a landmass. The researchers think it could actually be one of four things. It could be waves on the sea. It could be gas bubbles rising from the sea floor. Or the magic island could be solids created in the freezing temperatures of winter, but released to float by late spring temperatures. Or the Ligeia Mare could have smaller solids, similar to silt, suspended in the sea.

Whatever the cause of the magic island, the scientists believe that it is related to the seasonal transition from spring to summer.

An environment like our own

Titan has exhibited many similarities to Earth, including evidence of changing seasons. Forces such as wind and rain help shape landscapes surprisingly like our own. Titan is the only moon known to have a substantial atmosphere. As on Earth, Titan's air consists largely of nitrogen.

Among its mountains and valleys, Titan has many oceans and lakes. But they aren't made of water. Instead, Titan's glistening raindrops are made of liquid methane and ethane, which fill the moon's rivers, lakes, and seas, and then evaporate to form more rainclouds, much as water does on Earth.

"Titan is the only other world in the solar system – the only one that we know of in fact – that has stable liquids at its surface," says Hofgartner. "The liquids raise the question of habitability on Titan." But, he insists, this discovery simply helps us better understand the similarities between the two liquid cycles.

"Likely, several different processes – such as wind, rain and tides – might affect the methane and ethane lakes on Titan. We want to see the similarities and differences from geological processes that occur here on Earth," Hofgartner said in a news release. "Ultimately, it will help us to understand better our own liquid environments here on the Earth."

Finding a "magic island"

Hofgartner and other researchers began examining Cassini's images in search of changes as Titan's northern hemisphere moves from its spring toward its summer solstice, which will happen in 2017 (one "year" on Saturn takes 29 Earth years). As the sun shines on the moon's surface, the researchers expect to see more activity. "We're trying to look at these lakes over a long time span to see changes," says Hofgartner.

The scientists studied images taken of the sea over the months since spring began in 2009. By shifting their attention back and forth between the images, they were able to spot a bright feature in the Ligeia Mare.

"First you get a little bit excited about what it could be, but our scientific instincts kick in and the first thing we think is that it's some sort of image processing error," says Hofgartner. "A big part of the actual scientific work was to go through and show that this feature is not consistent with any imaging processing errors."

Once the researchers were confident they had found something real, they checked the data to make sure the "magic island" wasn't a feature that was there the whole time.

Next, the scientists were able to check their hypotheses against the data. "It appeared and then disappeared," says Hofgartner. That ruled out the possibility of a new island being created by volcanism, as it would have still been there. The researchers were able to observe the same location exactly one tide cycle later and the feature was gone, so it couldn't have been something revealed by a low tide.

The four hypotheses mentioned earlier are all equally possible, says Hofgartner. It will take more research to build data to refute or reinforce these ideas.

What's next

"We're going to do future observations of this area, so hopefully that will give us good constraints and we'll be able to narrow it down to one of those possibilities," says Hofgartner.

The next radar observation will be in August of this year, so he won't have to wait long. Seasons on Titan last more than seven Earth years, so they have plenty of time to do more research even after that.

Long-term, researchers hope to launch a robotic boat into one of Titan's seas to explore it further, but first they need to know more about the environment, says Hofgartner.

A young scientist

As a third year graduate student at Cornell University, Hofgartner chose to study planetary science. "I wanted to be a part of active exploration and discoveries as they're happening," he says. He didn't expect to have such success so early in his scientific career, but "it was awesome to accomplish that goal and make this a reality."

Hofgartner said it was thrilling to discover the "magic island" because, "In astronomy, when you see changes it's not a totally uncommon thing, but it's still rare enough that it's an exciting thing any time you see any kind of changes."