Tiny bubbles: bonanza for study of climate change's impact on marine methane

The continental margins off the US East Coast are sending bubbles of methane into the water. These naturally occurring seeps could provide a critical baseline to gauge the effect of climate change on these emissions.

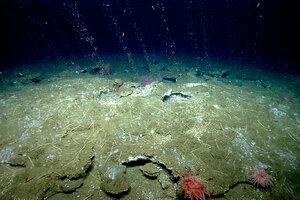

Methane streaming from the seafloor at ~425 meters (1400 ft) water depth offshore Virginia. Such naturally occurring methane seeps are a bonanza for scientists trying to understand undersea methane's responses to climate change.

Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition.

Researchers have discovered hundreds of naturally occurring methane seeps along the margins of the East Coast's continental shelf – a bonanza for marine scientists trying to understand undersea methane's potential responses to climate change.

In effect, these seeps – and tens of thousands of others suspected to be bubbling up along continental margins around the world – could provide a critical baseline for long-term measurements to gauge the effect of climate change on their activity.

So far, researchers have only developed estimates for the flow of methane out of so-called "cold seeps" sitting on the continental shelves – somewhere between 9 million and 72 million tons a year of the gas. The new results point to an underappreciated source of marine methane.

Molecule for molecule, methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, although its residence time in the atmosphere is much shorter. Yet much of the methane rising from these seeps never reaches the atmosphere, researchers say. These seeps generally are too deep – but just barely.

Some 77 percent of the 570 newly found seeps appear within a depth range representing an upper boundary where temperatures generally are low enough and pressures high enough to maintain the methane in a frozen form known as methane hydrates. Above that range, the hydrates are susceptible to melting.

At these depths, methane in the bubbles readily migrates through the bubbles' boundaries to diffuse into the ocean, because the ocean is relatively methane-poor. As the methane exits, oxygen and nitrogen in the water replace it, to be released when the bubbles bob to the surface and pop.

This process that can reduce oxygen levels near the seeps. In addition, the methane can become food for microorganisms that give off CO2 as a byproduct, rendering the water more acidic. Indeed the methane initially trapped as a hydrate comes from bacteria munching organic material in the sediment that has settled on the continental margin or, for deeper deposits, on the deep-sea floor.

Yet this is merely an outline, researchers say. Many of these processes are poorly understood or measured. With such seeps in relatively easy reach of research vessels along the East Coast, answers to a wide range of questions researchers have about processes affecting the methane may be answered more quickly that might otherwise have been the case. The only other continental margins where these seeps have been detected have been in the Arctic, hence far less accessible.

Indeed, the discovery has provided something of a "Wizard of Oz" moment, suggests Carolyn Ruppel, a researcher with the US Geological Survey office in Woods Hole, Mass., who heads of the agency's Gas Hydrates Project. Compared with the Arctic, these seeps have existed undetected in researchers' own backyard.

"It's pretty shocking to think that this has just been sitting out there all these years and no one ever found it," says Dr. Ruppel, a member of the team reporting the find in the current issue of the journal Nature Geoscience. From a science standpoint, the continental margin along the East Coast is the most intensively studied in the US, she notes.

The team mined sonar data gathered on research cruises conducted between 2011 and 2013, mainly via a 2012-13 project known as the Atlantic Canyons Undersea Mapping Expeditions (ACUMEN) – a partnership between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and several research institutes.

The sonar data the team used covered some 36,000 square miles of ocean, with the sonar fine-tuned to pick up seep bubbles as well as to conduct its mapping work. Mississippi State University marine scientist Adam Skarke and an undergraduate student from Brown University, Mali’o Kodis, poured over the data hunting for signs of the seeps, while Ruppel and other members of the team provided the analysis. Dr. Skarke is the lead author of the paper formally reporting the results in Nature Geoscience.

At least 570 seeps appeared at depths ranging from 164 feet to nearly 5,600 feet and were spread along the margin from off Cape Hatteras in North Carolina to the Georges Bank east of Cape Cod.

Although the bubbles have yet to be sampled directly, methane is their most plausible content, the researchers say. The other possibility would be hydrogen sulfide, but that is toxic to many forms of marine life. Several seeps had thriving shellfish populations around them.

Although some of the shallower seep emissions could, in principle, result from warming ocean waters melting methane hydrates, the team noticed carbonate minerals at these seeps. This suggested that methane-bearing fluids have been rising through the sediment for at least 1,000 years.

Noting that most of these seeps appear near the boundary between hydrate-friendly and hydrate-hostile depths, where they are vulnerable to rising ocean temperatures, University of Rochester marine chemist John Kessler suggests that the results will lead to a long queue of scientists hoping to understand the climate/continental-margin methane connection. Others will be interested in the impact of this methane on the ocean's carbon cycle and on potential ecosystems that could build around these so-called cold seeps – lower temperature versions of the hydrothermal seeps along mid-ocean ridges, where molten, recycled crust is welling up to repave the planet.

Indeed, Ruppel notes that several groups already have received funding to begin follow-up studies. And for many of them, they need go no farther than their own marine "backyard."