Buried beneath Stonehenge, even more henges?

Using ground-piercing radar and other high-tech equipment, scientists have detected at least 17 other ancient monuments buried beneath Stonehenge.

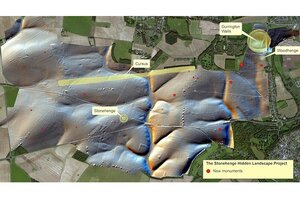

The red circles mark the spots where archaeologists found satellite shrines around Stonehenge.

© LBI ArchPro, Wolfgang Neubauer

The megaliths of Stonehenge, which were raised above England's Salisbury Plain some 5,000 years ago, may be among the most extensively studied archaeological features in the world. Still, the monument is keeping secrets.

Scientists have just unveiled the results of a four-year survey of the landscape around Stonehenge. Using non-invasive techniques like ground-penetrating radar, the researchers detected signs of at least 17 previously unknown Neolithic shrines.

"Stonehenge is undoubtedly a major ritual monument, which people may have traveled considerable distances to come to, but it isn't just standing there by itself," project leader Vincent Gaffney, an archaeologist at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., told Live Science. "It's part of a much more complex landscape with processional and ritual activities that go around it. That's very different from how this has been viewed before. The important point is Stonehenge is not alone. There was lots of other associated ritual activity going on around it." [See Images of Hidden Stonehenge Monuments]

Scholars still aren't sure why Stonehenge was built, as the monument's Neolithic creators left behind no written records. But the ruins, which align with the sun during the solstices, stand as an impressive feat of prehistoric engineering. The biggest stones at the site, known as sarsens, are up to 30 feet (9 meters) tall and weigh 25 tons (22.6 metric tons); they are believed to have been dragged from Marlborough Downs, 20 miles (32 kilometers) to the north.

At the newfound satellite shrines around Stonehenge, Gaffney and his team revealed underground impressions, presumably left by wooden post holes, stones and ditches — some of which extend up to 13 feet (4 m) deep. Images created with geophysical prospecting tools show that some of these smaller monuments had a concentric circle design, much like Stonehenge.

The researchers also peered inside the Cursus, an immense prehistoric enclosure to the north of Stonehenge that dates back to about 3500 B.C. Stretching about 1.8 miles (3 km) long and 330 feet (100 m) wide, the Cursus had been deemed a barrier to Stonehenge, but it was so big that no one really knew what was inside of it, said Gaffney.

When the researchers surveyed this area, they found a large pit buried on the eastern end of the Cursus. This pit was aligned with Stonehenge's "avenue," a processional path that lines up with the sun at dawn during the mid-summer solstice. The team also found a matching pit at the other end of the Cursus. This pit is aligned with the Heel Stone at the entrance to Stonehenge, which is aligned with sunset during the solstice, Gaffney said.

"Suddenly, you've got a link between this very large monument and Stonehenge through two massive pits, which appear to be aligned on the sunrise and sunset on the mid-summer solstice," Gaffney said.

The researchers also mapped dozens of burial mounds in the area, including a long barrow that dates back to an era before Stonehenge. The team detected a timber building buried inside the mound, and the project leaders think this structure might have been used for the ritual inhumation and defleshing of the dead.

Gaffney said it will take his team about a year just to process all the data they collected during their 120 days of fieldwork over the span of four years. And then it will likely be up to English Heritage (the government body in charge of archaeological and historic sites) to decide which features to dig up in a more traditional excavation. Further study should help reveal the ages of these monuments, pits and burial mounds, and help explain how Stonehenge evolved over time.

The findings were revealed as part of the British Science Festival and will be featured in a new BBC Two series, "Operation Stonehenge: What Lies Beneath," which will air in the U.K. Thursday (Sept. 11) at 8 p.m. BST. A U.S. version of the special, dubbed "Stonehenge Empire," will air on the Smithsonian Channel Sept. 21 at 8 p.m. ET/PT. The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project is led by the University of Birmingham with the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- In Photos: A Walk Through Stonehenge

- Megalithic Mysteries: Test Your Stonehenge Smarts

- Gallery: Aerial Photos Reveal Mysterious Stone Structures

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.