Liquid water once flowed on Mars – but only episodically, study suggests

Volcanic eruptions on Mars may have triggered the climate conditions that allowed liquid water to pool on the Red Planet early in its history, according to a new study published Sunday.

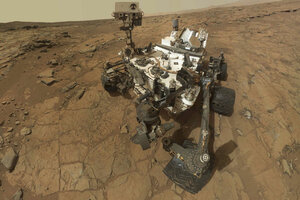

A self-portrait of the Mars rover Curiosity is seen in this 2013 handout image, courtesy of NASA. Scientists with NASA's Mars rover Curiosity team said they found evidence of a fresh water lake at the rover's landing site.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Reuters/FILE

Volcanic eruptions on Mars could have triggered the climate conditions that allowed liquid water to flow and pool on the Red Planet early in its history, according to a new study.

The presence of water would have been episodic, the study indicates. But those episodes would have been frequent enough over a span of 100 million to 200 million years to sculpt channels and valleys on the surface, particularly at low latitudes.

Conditions also would have been adequate enough to form minerals that testify to water's presence – evidence uncovered by orbiters and landers the US and Europe have sent to Mars, most recently NASA's rover Curiosity, which is exploring the planet's Gale Crater.

The new study, published Sunday in the journal Nature Geoscience, represents an attempt to reconcile abundant surface evidence for water in Mars's past with the idea that the sun would have been far cooler some 4.1 billion years ago, after the planet had finished forming and had endured an impact that left Hellas Basin, a sprawling dent in Mars's southern hemisphere that covers roughly 1.5 million square miles and reaches a depth of more than 23,000 feet.

The topic is of keen interest because water is considered a necessary ingredient for the emergence of life. But it's unclear whether Mars may have been warm enough early in its history to allow for the presence of seas and oceans, or whether the water on the surface was transient.

Mars “was more Earth-like, at least in places and at times, but we don't know how much like Earth it really was,” says James Bell III, a planetary geologist at Arizona State University in Tempe.

“There's plenty of evidence that the water has been sporadic, minor over much of the planet and only very localized,” says Dr. Bell, who did not take part in the new study.

But others have found evidence that suggests otherwise, he adds.

During the period when Mars is thought to have been warm and wet, the sun was about 25 percent dimmer than it is today. Modeling studies published two years ago suggested that, even with a thick atmosphere of carbon dioxide, temperatures at the planet's surface wouldn't have risen above freezing anywhere – unless the tilt of the planet's axis approached 40 degrees.

Some studies have indicated that early in Mars's history, the planets tilt could shift by 60 degrees or more over periods of several million years. But the model indicated that even with the appropriate tilt, the wrong parts of the planet would have warmed. Any melt water would have been in the wrong place to explain the extensively layered landscape and deeply etched valleys and canyons at lower latitudes.

The team of French and US researchers that conducted the modeling efforts concluded that some mechanism other than the planet's early climate “must occur to explain the evidence for liquid water.” The results were published online by the journal Icarus in October 2012.

An accompanying study in the same issue explored non-climate mechanisms that could have in effect opened the spigot on Mars, including volcanic activity. The new study published Sunday is an initial effort to explore volcanism's role.

It found that “volcanism can bring the temperature on early Mars above the melting point for decades to centuries,” said James Head III, a planetary scientist at Brown University in Providence, R.I., and one of the study's two authors. That warmth would have allowed ice to melt, filling lakes and sending water tumbling along streams and rivers.

The grouping of valleys and lakes at low latitudes coincides with a prolonged period of eruptions that peaked about 3.7 billion years ago, according to Dr. Head and the paper's lead author, Itay Halevy, a researcher with the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. The large-scale eruptions, more effusive than explosive, are thought to be similar to the eruptions that formed extensive formations such as the Columbia River Flood Basalts, or the Deccan and Siberian Traps in India and Russia.

These eruptions would have taken place in fits and starts over a 100 million- to 200 million-year span, with a cumulative eruption time of perhaps 10,000 years, the duo suggests.

Previous modeling work looked at the impact of water vapor and carbon-dioxide on Mars's early climate. The new study modeled the effect of sulfur dioxide – like carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas – and tiny aerosol particles bearing sulfuric acid.

Greenhouse warming from the intense pulses of sulfur dioxide more than offset the cooling effect of the aerosols that formed, the results indicated. This would have allowed peak daily temperatures at low latitudes to rise above freezing. Most of the water would have appeared as ice in the south polar region, as snow and ice on the planet's southern highlands, or bound up in the Martian soil, the researchers posit.

The episodic flow still would have allowed water-bearing minerals to form and get transported across the surface. Once the volcanism began to subside, so did the warm periods.

The study “makes a reasonable argument that's consistent with a lot of data,” says Bell. “But there's still a lot of other data that's not consistent” with the idea of water's limited presence on the planet.

NASA's MAVEN mission, which aims to help scientists reconstruct Mars' climate history, will provided important insights, Bell suggests, cautioning that it is testing but one hypothesis about water on Mars and how the planet could have lost it. Other vital clues, he says, will come when missions to Mars return of samples from various locations, allowing scientists to apply lab techniques that even the highly capable Curiosity can't match.