Ancient skull could hold clues to humanity's oldest murder mystery

A 430,000 year-old Neanderthal skull found in northern Spain shows signs of foul play.

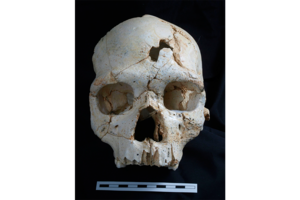

This is a frontal view of Cranium 17 showing the position of the traumatic events T1 (inferior) and T2 (superior).

Javier Trueba / Madrid Scientific Films

Call it the ultimate cold case, a murder that predates the emergence of modern humanity by over 200,000 years.

Northern Spain’s Sima de los Huesos archeological site is home to a slew of early hominid remains, including the near-complete Neanderthal skull dubbed “Cranium 17.” An analysis of the skull, published Wednesday in the journal PLOS ONE, suggests that it might actually be evidence in a case of prehistoric foul play.

Discovered more than three decades ago, Sima de los Huesos lies deep within the Cueva Mayor underground cave system. It consists of a 43-foot vertical shaft which contains the remains of some 28 individuals. It was unclear how and why the remains, which were dated to about 430,000 years old, came to rest there. Cranium 17 had to be reconstructed over 20 years from 52 fragments.

The completion of Cranium 17 revealed a striking record of its owner’s death, with two distinct holes, each caused by a severe blow, above the left eye. Researchers say the trauma would have been lethal.

It is possible that this hapless hominid could have died upon falling into the shaft – now believed to be the site of early funeral rites – but lead author Nohemi Sala, of the Centro Mixto UCM-ISCIII de Evolución y Comportamiento Humanos, believes otherwise.

To determine the cause of death, Dr. Sala and her colleagues conducted trajectory and contour analysis on the two lesions. The type and location of the fractures suggested that they were caused by separate blows from the same object. In other words, the injuries were consistent with a deliberate attack, probably from another person.

“For sure there has been violence throughout prehistory,” Sala says. “Unfortunately, it is difficult to find evidence in the fossil record, because we have only bones – no soft tissues – and interpersonal violence does not always leave a clear mark on the bone. Cranium 17 is an unusually clear case, like a ‘smoking gun.’ Something like that is not found every day.”

If Sala and colleagues are correct, Cranium 17 represents the earliest known case of violent murder. More than an archeological curiosity, the skull provides a window into the social behaviors of pre-human ancestors. Intra-species violence and warfare, once presumed to be relatively modern inventions, actually predate humanity by hundreds of thousands of years or more. Modern chimps, wolves, and even insects have been observed engaging in “conspecific” killing. This kind of violence, it seems, is deeply rooted in animal behavior.

“We believe that intentional interpersonal violence is a behavior that accompanies humans since at least 430,000 years ago,” Sala says, “but so is care of the sick or even the care of the dead. As a final speculation, we have not changed much in the last half million years.”