Who was Kennewick Man? DNA test offers surprising answer to mystery.

A new study of the remains of Kennewick Man suggests he is most closely related to native Americans, opening a new chapter in a two-decade saga.

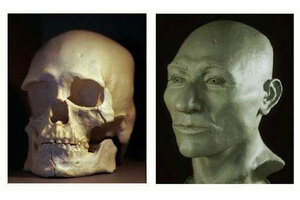

A left is a plastic casting of a skull from the bones known as Kennewick Man in Richland, Wash. At right is a clay model of Kennewick Man at the Columbia Basin College in Richland.

Elaine Thompson/AP/File and James Chatters/AP/File

For nearly 20 years, the rare, virtually complete, 8,500-year-old skeletal remains of an individual dubbed Kennewick Man have captivated scientists. They touch on the issue of the origins of North America's earliest inhabitants and open a window on what they went through as they occupied the continent.

A new genetic analysis, however, is prompting a fresh look at whether Kennewick Man's remains should remain available to researchers or whether they should be handed over to native Americans for burial as an ancestor.

An international team of researchers has analyzed DNA from Kennewick Man and has found that genetically, he is much closer to modern native Americans than to either of two groups scientists had tied him to previously.

Researchers had based that tie largely on features of Kennewick Man's skull. These features linked him more closely to Polynesians or indigenous Japanese known as Ainu than to native Americans.

That evidence played a major role in federal court decisions in 2002 and 2004 that blocked repatriation of the remains. The the courts concluded that Kennewick Man was too different physically and the remains too old to establish the cultural links needed to meet the requirements of the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

While the new study does not address the question of cultural connections, it does move the needle on the question of Kennewick Man's biological relationship to modern native Americans.

The new result is ironic, observes Eske Willerslev, an evolutionary biologist who heads the Centre for GeoGenetics at Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, where the analysis was conducted.

"The reason why we can come to this conclusion scientifically speaking is because the remains were kept out for science," says Dr. Willerslev, who led the study. At the same time, the result "shows that he was native American."

New technology, new answers

The results come on the heels of a 680-page book published last fall that pulled together the research to date on Kennewick Man, known to tribes in the Pacific Northwest, where the remains were found, as "Old Ancestor." The data were collected during two sessions over a total of 16 days conducted between 2005 and 2006.

The volume provides a portrait of a muscular man who tipped the scales at 163 pounds, stood about 5 feet, 7 inches tall, and died at the age of 40. Although he hunted deer or antelope, his diet appeared to consist mainly of fish or marine mammals. He was right-handed, adept at knapping flint, and was a survivor. His skeleton bears evidence of two significant injuries, included a projectile point embedded in his hip bone, speaking either to an attack or a hunting mishap.

Kennewick Man also was cited as evidence for the hypothesized migration of ancient ancestors of today's Polynesians and Ainu up along the edge of the western Pacific and across what is now the Bering Strait to North America.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, researchers had tried to extract DNA from Kennewick Man and analyze it. But the technology wasn't up to the task at the time, explains Morten Rasmussen, a geneticist at Stanford University and the lead author of a formal report on the study published today online by the journal Nature.

Newer methods of analysis can make sense of "the very degraded DNA in Kennewick Man, [and] that's absolutely key for addressing these questions," Dr. Rasmussen says.

The team, which also included researchers from Australia, Switzerland, and the United States, compared Kennewick Man's DNA with DNA from other groups around the world. The researchers found that among contemporary populations, Kennewick Man is most closely related to native Americans.

When the researchers compared Kennewick Man's DNA with that of Polynesians or Ainu, they found that Kennewick Man host no more DNA from these groups than do modern native Americans.

What happens now

The team tried to narrow relationships within the Americas. That was tougher because few native American tribes have agreed to give DNA samples, Willerslev says.

Of the small number of samples available, Kennewick Man was closer to native American groups from the Northwest. Among those, the closest link was with the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, one of five tribal groups in the region involved in efforts to repatriate the remains.

The researchers offer two scenarios that could have led to the genetic differences that exist between Kennewick Man and the Colville tribes. They could have split from a common group about 700 years before Kennewick Man lived. Or the Colville group could be direct descendants, with an additional influx of other genes working their way into the genomes of the Colville group during the past 8,500 years.

The team's results didn't allow them to pick an out-and-out winner among these two scenarios, says Rasmus Nielsen, a geneticist from the University of California at Berkeley and another member of the team. But, he adds, there is enough evidence to suggest that the second scenario may be the right one.

Assuming the results hold up to further scrutiny, the DNA data raise questions for of the United States Army Corps of Engineers, which is the custodian for Kennewick Man's remains. The remains are being curated at the University of Washington's Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle.

Native American groups that have pressed for repatriation are considering their next steps in light of the new study.

"We've always known and believed he was of native American ancestry," says Chuck Sams, spokesman for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, outside of Pendleton, Ore. The study "just reaffirms what we've always said."

"We're looking through our options and discussing it with the other tribes involved to determine how best to get repatriation done," he adds.

Officials with the Corps' Northwest Division office in Portland, Ore., say they will be spending the next couple of weeks reviewing the new data to see if Kennewick Man now qualifies for repatriation.

Step 1 involves a thorough review of the data to see if there is "substantial evidence" for classifying Kennewick Man as a native American, according to Gail Celmer, an archeologist with the Corps who oversees the agency's archeology program in the region.

Step 2 requires "a preponderance of evidence" that establishes cultural ties between Kennewick Man and groups claiming him as an ancestor. These ties range from biology, geography, and language to archaeological, anthropological evidence, and oral traditions.

Given the history of competing interests in Kennewick Man and past, expensive litigation over whether or not the remains should be repatriated, "we plan on being very thorough" with the upcoming review, adds Michael Coffey, spokesman for the Corps' Northwest Division office. "We want what we do to be upheld through a great deal of scrutiny. Given the history, we will be under the microscope."

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the name of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation.