Sinkholes on Titan? Unlocking origins of lakes on Saturn's largest moon

Saturn's largest moon is host to the solar system's only non-Earthly lakes and seas. A new study sheds light on how some of these may have formed.

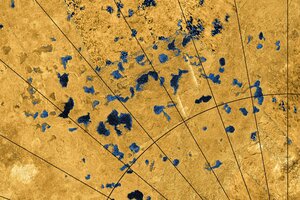

Radar images from NASA's Cassini spacecraft reveal many lakes on Titan's surface, some filled with liquid, and some appearing as empty depressions.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/USGS

Scientists may be starting to understand the origins of the mysterious lakes on Saturn’s moon Titan.

Titan’s surface is home to depressions filled with liquid hydrocarbons, much like seas and lakes on Earth. Those depressions, a new study suggests, are formed through a process similar to the creation of caves and sinkholes on Earth.

“We compared the erosion rates of organics in liquid hydrocarbons on Titan with those of carbonate and evaporite minerals in liquid water on Earth,” the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Thomas Cornet said in a statement.

“We found that the dissolution process occurs on Titan some 30 times slower than on Earth due to the longer length of Titan’s year and the fact it only rains during Titan summer,” Mr. Cornet added. “Nonetheless, we believe that dissolution is a major cause of landscape evolution on Titan and could be the origin of its lakes.”

Besides Earth, Titan is the only body in the solar system known to have surface lakes and seas, according to data collected by the joint NASA and ESA mission, Cassini.

These and other similarities have led many planetary scientists to view Titan as a kind of time capsule, one that shows what conditions on earth might have been like before life emerged, The Christian Science Monitor’s Pete Spotts noted.

“Though Earth is much warmer than Titan, the moon hosts an inventory of organic compounds thought to be similar to those on Earth before life took hold,” he wrote. “And the processes shaping Titan's surface – from flowing liquids to volcanic action – mirror those of Earth.”

The new study, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets in May, provides further support for comparing Titan and our planet. Though the moon’s icy surface temperatures – roughly minus 292 degrees Fahrenheit — means that liquid methane and ethane, not water, dominate its surface, Cornet and his team found that Titan’s lakes resemble Earth’s caves, sinkholes, and sinking streams.

These Earthly features, known as karstic landforms, result from erosion of dissolvable rocks, such as limestone and gypsum, in groundwater and rainfall. How fast the rocks erode depends on factors such as humidity, rainfall, and surface temperature. The scientists, assuming that Titan’s surface is covered in solid organic material and that the main dissolving agent is liquid hydrocarbons, calculated how long it would take for parts of Titan’s surface to create these features.

The resulting time frame shows it takes about 50 million years to create a 300-foot depression at Titan's relatively rainy polar regions, consistent with the youthful age of the moon's surface. In the moon’s less rainy areas, the timescale is much longer: about 375 million years.

Cornet acknowledged some uncertainties with the calculations, but noted that the figures are consistent with Titan’s relatively youthful billion-year-old surface.

And despite the differences between Titan and Earth, the geological process that leads to the lakes’ formation looks surprisingly similar.

“By comparing Titan’s surface features with examples on Earth and applying a few simple calculations, we have found similar land-shaping processes that could be operating under very different climate and chemical regimes,” said Nicolas Altobelli, ESA's Cassini project scientist.

“This is a great comparative study between our home planet and a dynamic world more than a billion kilometers away in the outer solar system,” he added.