Kepler 452b: NASA finds 'cousin' to Earth in age-old quest for other worlds

Kepler 452b: NASA announced Thursday that its planet-hunting mission, Kepler, has found an exoplanet that very closely resembles our own.

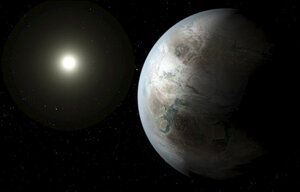

An artist's concept depicts one possible appearance of the planet Kepler-452b, the first near-Earth-size world to be found in the habitable zone of a star that is similar to our sun. The planet, which is about 60 percent bigger than Earth, is located 1,400 light years away in the constellation Cygnus, scientists told a news conference on Thursday.

T. Pyle/JPL-Caltech/Ames/NASA/Reuters

NASA has found Earth’s closest lookalike to date.

The space agency announced Thursday that its planet-hunting mission, Kepler, has discovered an exoplanet that is comparable to our own in age and size, orbiting a Sun-like star at a distance that makes it neither too hot nor too cold to support life.

Kepler 452b, as the planet is called, is the smallest known planet outside our solar system that is in the habitable zone of a G2-class star, like the Sun. It is about 6 billion years old, 60 percent larger than the Earth in diameter, and sits in the constellation Cygnus, about 1,400 light-years away from Earth.

Its discovery – 20 years after scientists first proved that stars other than our own host planets – marks a milestone in humankind’s 2,500-year-old quest for other worlds.

The new planet circles its Sun-like star in an orbit that lasts 385 days, placing it firmly in the zone that scientists consider habitable – where temperatures are warm enough for there to be liquid water on the surface.

"Today the Earth is a little less lonely, because there’s a new kid on the block," Jon Jenkins, Kepler data analysis lead at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., said at a Thursday news conference announcing the discovery. "We believe … that this is the nearest thing that we’ve found to an Earth system analogue, a twin system to our own."

John Grunsfeld, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate at the agency’s headquarters in Washington, called the new planet a "close cousin to the Earth."

It wasn’t until the 1990s that scientists confirmed that suns across the universe host their own planets. But the quest to find another habitable planet dates as far back as the ancient Greeks and Romans, whose philosophers challenged their contemporaries to conceive of the universe as infinite, and populated with a multitude of inhabited worlds.

Roman poet Titus Lucretius Carus is most frequently credited with originating the idea that the universe is infinite, in his poem "On the Nature of Things": " 'Tmust be confessed in other realms there are / Still other worlds, still other breeds of men, / And other generations of the wild."

During the Renaissance, Giordano Bruno disputed the uniqueness of the sun, suggesting in 1584 that the stars were other suns like ours, with their own planets. For his efforts, he was burned at the stake for heresy.

But all this remained pure conjecture until the development of the telescope in the early 17th century. Within a century or so, astronomers began noticing that stars varied in their brightness, and that they moved with respect to one another.

In 1925, Edwin Hubble proved the existence of other galaxies – clusters of stars similar to the Milky Way. His discovery "forever alters our view of the universe," according to NASA.

Seventy years later, Swiss astrophysicists Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz discovered the giant planet 51 Pegasi b, the first planet found to be orbiting a main-sequence star. The hunt for Earthlike planets has since taken on growing sophistication, through tools such as the Hubble Space Telescope, the Spitzer Space Telescope, and the Canadian telescope MOST. Spitzer in particular has been crucial in discovering water on an exoplanet.

Kepler’s launch in 2009, and developments in data interpretation since, have pushed the quest for habitable worlds further forward. Including the discovery of 452b, Kepler has now identified a total of 4,675 exoplanets.

And while there’s still plenty we don’t know about our newly discovered "cousin," scientists are optimistic about the future. Projects such as the James Webb Space Telescope and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), scheduled to start in the next few years, suggest NASA has every intention of continuing the search for the age-old question: Are we alone in the universe?

"This is a great time we’re living in," said Dr. Queloz, who was present at Thursday’s conference. "This is just the beginning of a very long journey."