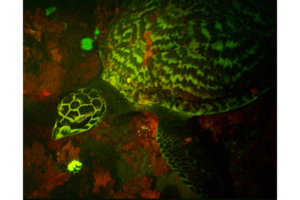

Divers spot glow-in-the-dark turtle

In the first instance of reptilian biofluorescence observed in a wild reptile, divers near the Solomon Islands spotted a hawksbill sea turtle glowing bright red and green.

Divers spotted a biofluorescent turtle swimming near the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific.

Copyright David Gruber

Below the tropical waves near the Solomon Islands, nighttime divers spotted a psychedelic vision: an endangered sea turtle glowing bright red and green.

The divers immediately began filming the creature, a hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricate), following it for a few minutes until it swam away.

"It was such a short encounter," said David Gruber, an associate professor of biology at Baruch College in New York City and a National Geographic emerging explorer. "It bumped into us and I stayed with it for a few minutes. It was really calm and letting me film it. Then it kind of dove down a wall, and I just let it go." [See Images of Glowing Sea Turtle and Other Light-Emitting Creatures]

The finding is an important one: Though researchers have already found biofluorescence in aquarium-housed loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta), this is the first time scientists have identified biofluorescence in a reptile in the wild, Gruber told Live Science.

Biofluorescence occurs when an organism absorbs light from an outside source, such as the sun, transforms it and then reemits it as a different color. (This is different from bioluminescence, a chemical reaction that helps creatures, such as fireflies, flash light. Some animals also host bioluminescent bacteria, such as flashlight fish.)

The field of biofluorescence has taken off in the past decade, with researchers identifying all sorts ofbiofluorescent marine animals, including corals, fishes, eels and sharks. The work is so groundbreaking that Gruber and his colleagues helped make a forthcoming Nova special called "Creatures of Light," he said.

Turtle time

The divers weren't looking for glowing sea turtles on July 31, Gruber said. They had waited until nightfall — luckily they had a full moon — and took a boat to shallow water near Nugu Island, located in the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific. Recent news of crocodile attacks had them on guard, but they dove into the water, and used blue lights to look for biofluorescent sharks.

Then, the turtle came along.

"This turtle almost seemed completely attracted to the blue lights that we were filming with, and just swam right into me," Gruber recalled.

Under the blue lights, the turtle fluoresced "a brilliant green," on its head, flippers and plastron (the underside of its shell), he said.

The shell glowed both red and green, but it's likely the red came from biofluorescent algae, Gruber said.

"This turtle was just hanging out with us. It was in love with the lights," Markus Reymann, the other diver and the director of TBA21-Academy, a group that pairs artists and scientists together, said in a National Geographic video. "And it was glowing neon yellow."

Gruber later showed the film to Jeanette Wyneken, a professor of biology at Florida Atlantic University. From the looks of it, the 3-foot-long (1 meter) turtle looks like a female that is nearing adulthood, she told him.

Gruber also spoke to some locals who kept captive juvenile hawksbill sea turtles, and found that they fluoresced green under a blue light. [The 7 Weirdest Glow-in-the-Dark Creatures]

Critically endangered

The hawksbill turtle breeds in more than 80 countries and is found in the Caribbean Sea and Indo-Pacific Ocean, but it's also critically endangered, partly because of climate change, illegal trade, bycatch (in which commercial fishers catch turtles by mistake while collecting other fish) and hunting, Gruber said.

"The Solomon [Islands] are one of the places where there's a large rookery of them," he said. "It's like a little hotspot where the hawksbills are still very healthy."

But it's difficult to study a critically endangered animal. Instead, Gruber says he'll probably study biofluorescence in the loggerhead turtle first, just because they're more accessible.

Still, it's anyone's guess why turtles would need to glow.

"It could be a way for them to communicate, for them to see each other better, [or] to blend into the reefs," which are also biofluorescent, Gruber said. "It adds visual texture into the world that's primarily blue."

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

- Photos of the Largest Fish on Earth

- Images: Fish Secretly Glow Vibrant Colors

- In Images: The Menagerie of Tiny Alienlike Creatures Under the Sea

Copyright 2015 LiveScience, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.