Were dinosaurs really warm blooded? Eggshells hold hints.

Through chemical analysis of fossilized eggshells, scientists have estimated the internal body temperatures of both oviraptors and long-necked sauropods.

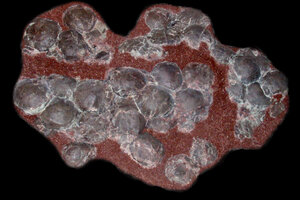

A large titanosaur clutch, cleaned.

Courtesy of Luis Chiappe

The answer to a long-standing paleontological debate may come from an unlikely source: Eggshells. Very old eggshells.

Using fossilized eggs from Argentina and Mongolia’s Gobi desert, researchers have calculated the body temperature of titanosaurs and oviraptors, respectively.

By determining the core temperatures of these and other long-extinct species, scientists can make inferences about their metabolisms and behaviors, finds a study, led by UCLA researcher Robert Eagle, that appeared Tuesday in Nature Communications.

Paleontologists have long attempted to estimate dinosaurs' body temperatures. Some have suggested that they were cold-blooded and lizard-like; others have propose a warmer, more mammalian, metabolic model. But while previous studies revolved mostly around modeling and statistics, Dr. Eagle based his analysis on chemistry.

The hard exterior of an eggshell is made up of a mineral called calcium carbonate, a compound of carbon, oxygen, and calcium. When this mineral is produced, two rare chemical isotopes – carbon-13 and oxygen-18 – tend to bond together. With a mass spectrometer, researchers could measure these isotopic bonds in fossilized eggs. Eagle notes that C-13 and O-18 cluster more at cold temperatures, and less so at hot temperatures.

“So the abundance of these bonds reflects the body temperature of the female when the eggshell forms,” Eagle explains.

According to Eagle’s findings, large sauropod dinosaurs were probably warm blooded. Like modern mammals and birds, they would have generated body heat internally. Surprisingly, oviraptors had low core temperatures and slow metabolic rates compared to other dinosaurs and modern birds. According to Eagle, they were likely “intermediate” ectotherms – only partly cold blooded.

“There are two possible explanations,” Eagle says. “One, their ability to generate heat internally [may have been] different. Alternatively, the very large dinosaurs may have had higher capacity to retain environmental heat due to their gigantic size.”

But why does it matter how hot or cold a dinosaur’s blood ran?

Body temperature is directly linked to metabolic rate. Warm-blooded animals, also known as endotherms, are capable of internal body regulation. As such, mammals and birds are suited to prolonged physical activity. But cold-blooded animals, or ectotherms, rely on environmental heat sources, and are usually capable of strenuous activity only in short bursts.

So by determining the body heat of dinosaurs we can understand parts of their physiology, make inferences about their hunting methods, and determine their environmental range.

“This is just the beginning, and the first application of this technique,” Eagle says. “There is a huge array of questions that can be asked.”