How the ocean’s frozen methane is being unlocked by climate change

Scientists have examined bubble plumes that suggest subsurface warming is causing once-frozen methane to be released as gas.

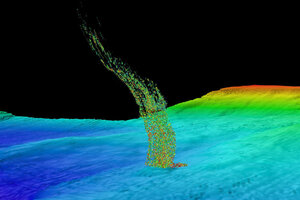

Sonar image of bubbles rising from the seafloor off the Washington coast.

Brendan Philip/University of Washington

Scientists from the University of Washington have spotted bubble plumes off the Washington and Oregon coast, suggesting that frozen methane deep in the ocean is thawing.

More importantly, this conversion means it is transforming a “dormant solid to a powerful greenhouse gas,” UW's Hannah Hickey writes in a press release.

What this might mean for climate change is uncertain, the researchers emphasized, though they said local marine life and fisheries will be affected.

Methane is an extremely potent greenhouse gas, with a pound-for-pound impact that is 25 times greater than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period.

Ironically, what appears to be driving the transition is climate change itself. The activity was detected about a third of a mile below the ocean’s surface, which experiences warmer temperatures, researchers said.

The team examined 168 methane plumes over the past decade, concluding that subsurface warming is the cause of the methane’s release. The researchers’ findings are to be published in the journal Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

“What we’re seeing is possible confirmation of what we predicted from the water temperatures: Methane hydrate appears to be decomposing and releasing a lot of gas,” H. Paul Johnson, the UW professor of oceanography who led the study, told Ms. Hickey. “If you look systematically, the location on the margin where you’re getting the largest number of methane plumes per square meter, it is right at that critical depth of 500 meters.”

“We see an unusually high number of bubble plumes at the depth where methane hydrate would decompose if seawater has warmed,” said Professor Johnson. “So it is not likely to be just emitted from the sediments; this appears to be coming from the decomposition of methane that has been frozen for thousands of years.”