Why sunscreen may be killing coral reefs

An ingredient found in more than 3,500 sunscreen brands may be contributing to the decline of coral reefs at popular beaches in Hawaii, the Caribbean and the US Virgin Islands, a study published Tuesday suggests.

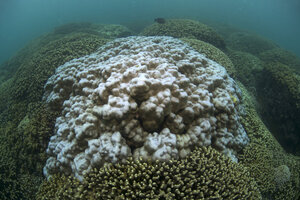

A bleached coral is shown in Kaneohe Bay off the east coast of Oahu, Hawaii, Aug. 13. An ingredient commonly found in sunscreen may be leaving coral more susceptible to bleaching, according to a study published Tuesday in Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology.

XL Catlin Seaview Survey/AP

For most beachgoers, sunscreen is a necessity, but a common ingredient found in many sunscreens can prove toxic to coral, a study released on Tuesday found.

The ingredient, oxybenzone, has a particularly damaging effect on young coral, limiting their ability to reproduce and likely contributing to the decline of coral reefs around the world, according to the study, which was published Wednesday in the Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology.

An international team of scientists, including researchers from the United States and Israel, found the highest concentrations of oxybenzone near coral reefs at popular beaches, including in Hawaii and the Caribbean.

Even a tiny amount of the ingredient – 62 parts per trillion, or a drop of water in six olympic-sized swimming pools – can prove toxic to young coral, but in higher concentrations, it can also prove fatal to adult coral.

Swimmers aren't the only vehicles delivering the chemical into the water. The researchers say nearby wastewater discharges can also harm the coral.

“Oxybenzone pollution predominantly occurs in swimming areas, but it also occurs on reefs 5 to 20 miles from the coastline as a result of submarine freshwater seeps that can be contaminated with sewage,” says Omri Bronstein, a zoologist from Tel Aviv University, one of the principal researchers, in a statement.

Craig Downs, a scientist at the non-profit Haereticus Environmental Laboratory in Virginia, who led the study, says the research helps explain why scientists aren’t seeing baby corals in existing reefs at many popular beaches.

While applying sunscreen is often suggested before snorkeling or scuba diving around a reef, researchers say the oxybenzone in the lotion can compromise the health of the coral leaving it susceptible to "bleaching," the loss of the beneficial zoozanthellae that live in the coral and lend the reef it's color. Such bleaching was also associated with events like El Niño, which warms up the surface temperature of the sea, they add. The ingredient can also prompt the coral to develop a hard coating and effectively encase itself in its skeleton and die.

Between 4,000 and 6,000 tons of sunscreen ends up in coral reefs every year, the National Park Service estimates, while popular beaches in Hawaii and the Caribbean have concentrations of more than 12 times that amount, seawater test show.

In the US Virgin Islands, the concentration of oxybenzone is 23 times higher than the minimum amount that can prove toxic to corals, the researchers found.

The Park Services reports that there’s no completely “reef-friendly” sunscreen, but beach visitors can consider sunscreens that contain natural ingredients like titanium oxide and zinc oxide, minerals which are often found in children’s sunscreens, as alternatives to those with oxybenzone.

Wearing sun-protecting clothing, including long-sleeves, hats, and rash guards in the water, can also reduce the risk of harm to coral, the researchers say.

They hope the study will help draw attention to the risk oxybenzone poses to coral and the marine environment more generally and encourage the use of alternatives to harmful sunscreens.

“Current concentrations of oxybenzone in these coral reef areas pose a significant ecological threat,” Dr. Bronstein says.

This report contains material from Reuters.