Saturn's ring mystery: Why are opacity and density mismatched?

A new analysis contributes to a body of research aimed at uncovering the mass and origin of the planet's rings.

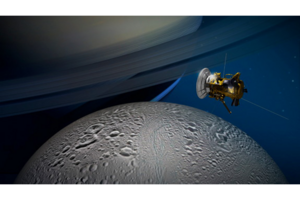

Artist's illustration of NASA's Cassini spacecraft flying by Saturn's icy moon Enceladus.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

In studying the mass of Saturn’s rings, astronomers have stumbled on a surprising finding: more opacity does not necessarily mean more mass, as one might expect.

"Appearances can be deceiving," Phil Nicholson, an astronomy professor at Cornell University, said in an announcement.

"A good analogy is how a foggy meadow is much more opaque than a swimming pool, even though the pool is denser and contains a lot more water," explained Dr. Nicholson, who participated in a recent analysis of data collected by the Cassini spacecraft mission.

Astronomers are trying to determine the density of Saturn’s rings to figure out how old they are and how they formed. In this analysis, they looked at the density of Saturn’s B Ring, the largest and most opaque of them all, and made of billions of particles of mostly water ice. They found that levels of opacity were different across the width of the B Ring, even while the mass did not vary much along this span.

This phenomenon had already been observed in studies of Saturn’s other rings, leading scientists to conclude that there’s little correlation between a ring’s opacity and the amount of particulate material it contains.

Scientists had already proposed that the B Ring has less mass than its opacity would indicate, but this new analysis is the first to measure the ring and confirm this to be true.

Now scientists just have to figure out why this is the case.

"At present it's far from clear how regions with the same amount of material can have such different opacities,” Matthew Hedman, the study's lead author and a physics professor at the University of Idaho, said in an announcement.

“It could be something associated with the size or density of individual particles, or it could have something to do with the structure of the rings," he said.

By analyzing spiral density waves in the ring, scientists were able to determine its mass. These waves are created by gravity from Saturn and from its moons as it tugs on the particles. The shape of the wave is informed by the amount of mass in the part of the rings where the wave is located, researchers say.

"By 'weighing' the core of the B ring for the first time, this study makes a meaningful step in our quest to piece together the age and origin of Saturn's rings," Linda Spilker, a Cassini project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said.

"The rings are so magnificent and awe-inspiring, it's impossible for us to resist the mystery of how they came to be," she said.

Cassini scientists say that the mass of the B Ring is unexpectedly low, considering that it’s significantly more opaque than other, denser rings. To them, B Ring's low mass is an indication that it’s young by space standards, maybe a few hundred million years instead of a few billion. This is because astronomers expect that rings with less mass must have evolved faster than denser rings.

More research in 2017 is expected to confirm the rings' mass measurements, say astronomers, when Cassini is due to measure the mass of only Saturn as it completes its mission there. Cassini had already measured Saturn's gravity field, which helped determine the mass of the planet and its rings. Next year, astronomers will take the difference between the two measurements to confirm the mass of the rings.