Major population upheaval in Ice Age Europeans linked to climate change

The genomes of ancient Europeans reveal how human populations can change dramatically as a result of extreme climate fluctuations.

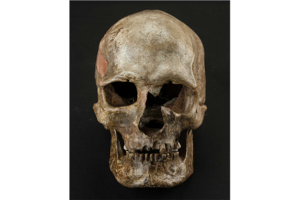

Geneticists sequenced the mitochondrial DNA of this prehistoric human unearthed in South Moravia, Czech Republic. They found a dramatic upheaval in the population of Europe likely resulting from the last ice age.

Courtesy of Martin Frouz

Little is known about human migrations and population changes in prehistory. Scientists often rely on scant archeological evidence to map anatomically modern humans' settlements.

So a team of geneticists dug into the genomes of ancient individuals unearthed across Europe to better understand who was living in the region. The specimens lived before, during, and after the last ice age, offering the researchers a glimpse into how the population handled the extreme conditions.

And the ancient hunter-gatherers' genomes suggested times were tough. When the massive glaciers retreated, the population of Europe looked dramatically different than it had before the land froze over.

"This change, which we call a turnover, was indeed strong and drastic," first author of the study Cosimo Posth tells The Christian Science Monitor in an interview. And this dramatic population turnover likely wiped out a human lineage scientists thought never reached Europe, according to a paper published Thursday in the journal Current Biology.

The researchers analyzed the mitochondrial DNA, inherited along the maternal lineage, from individuals living across Europe at varying times to map shifts in population.

When the ice spread across the continent, the people living in the northern regions were forced to migrate south for survival. As hunter-gatherers, these early Europeans were dependent on the environment for survival. This created a genetic bottleneck, with a significant loss of diversity from such a massive change.

Then, when the ice retreated some 14,500 years ago, there was an influx of new genetics. One explanation is that the glacial retreat allowed a new population to move into the region and intermingle their DNA.

"There was always this idea that for almost 35,000 years of human history, of prehistory from the first arrival into Europe until the Neolithic started, hunter-gatherers were kind of a continuum," Posth says. "But during these 35,000 years, there was a drastic change in climatic conditions. Those humans had to face these strong climatic events."

A surprise population erased by ice

When modern humans began dispersing across the globe, two main lineages emerged in mitochondrial genetics outside of Africa: haplogroup N and haplogroup M. Haplogroup M was thought to have only ever been present across Asia, Australasia, and the Americas. That lineage never reached Europe in prehistory, or so researchers thought.

This new study reveals that was not true.

"I thought this must be a mistake because I know that in Europe it is completely absent, at least in the population with European ancestry," Posth says. Perhaps the samples were contaminated or the researchers had made a mistake. But no mistake was made. The M haplogroup appeared in specimens from another location too.

Cristina Gamba, a geneticist at the Natural History Museum of Denmark who was not part of the study, says in an email to the Monitor "It is not completely surprising that they are able to identify mtDNA haplogroups absent in modern-day Europeans. Especially considering the large amount of climate-driven and migration events that have occurred since then. Demographic events such as bottlenecks and population replacements, among others, can explain changes in the allelic frequencies."

"This is especially true for the period around the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), as the climate change probably induced a strong population bottleneck and therefore loss of genetic diversity with the extinction of some lineages, such as the mtDNA haplogroup M," she says.

Although that mitochondrial lineage was likely wiped out by the ice age bottleneck, the prehistoric presence of haplogroup M in Europe could have significant implications. The lineage was thought to have been linked to a specific spread of modern humans into Asia, one of many different dispersals. But if haplogroup M was present in both Asia and Europe, perhaps there was just one major dispersal.

"Our prehistory is much more complicated than we had thought," Posth says. "We discovered an unknown chapter of human history."