Antarctic ice melt could drive sea levels up twice as high as we thought

Scientists say that their new projection isn't set in stone, but they urge communities to consider worst-case scenarios as they develop their climate-adaptation plans.

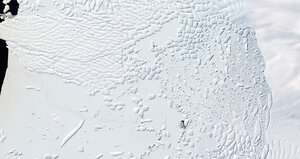

This satellite image provided by Nature/Knut Christianson, taken Jan. 9, shows the Thwaites Glacier and its ice cliff at the terminus of Thwaites Glacier, West Antarctica. A new study points says ice cliffs may lead to faster melting of Antarctic ice sheets and more sea level rise than previously thought with the Thwaites Glacier and its ice cliffs as the most likely place for this process to start.

Knut Christianson/Nature/AP/File

Many climate scientists have predicted sea-level rise over the next century as a result of manmade climate change. But in a new study, a pair of climate scientists say an accurate estimate of sea-level rise is actually double that of previous predictions.

In a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature, Robert DeConto at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and David Pollard at Pennsylvania State University say previous ice-sheet-climate models “under-appreciated” the melting of the Antarctic ice sheet.

But to better understand the future, and Antarctica’s potential role in it, Professor DeConto and Professor Pollard first looked to the past.

Using a three-dimensional ice sheet model, DeConto and Pollard reconstructed the Earth as it looked 3 million years ago during the Pliocene era and then 125,000 years ago during the Eemian era. During the Pliocene and Eemian, atmospheric carbon dioxide emissions were comparable to today’s levels, but sea levels were between 20 to 30 feet higher than they are today.

“So at a time in the past when global average temperatures were only slightly warmer than today, sea levels were much higher,” DeConto says in a press release. “Melting of the smaller Greenland Ice Sheet can only explain a fraction of this sea-level rise, most which must have been caused by retreat on Antarctica.”

DeConto and Pollard say Antarctic ice will melt faster than scientists previously thought, instead mirroring the melt rates from 125,000 and 3 million years ago. Current sea level rise predictions fail to account for “hydro fracturing,” say DeConto and Pollard, a process where meltwater on ice shelves causes big chunks of ice to crack off and fall into the water. And with the collapse of these vertical cliffs, "Antarctica has the potential to contribute greater than 1 meter (39 inches) of sea-level rise by the year 2100" if atmospheric emissions continue unabated, the authors warn.

“We are not saying this is definitely going to happen,” Pollard told The New York Times. “But I think we are pointing out that there’s a danger, and it should receive a lot more attention.”

In comparison, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts a 0.5 meter rise over 1990 levels by 2100. “Global sea level is projected to rise during the 21st century at a greater rate than during 1961 to 2003,” suggests the IPCC, at a rate of 4 mm per year through the 2090s.

And in 2013, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration concluded that there was a 90 percent chance that global mean sea level will rise between 0.2 and 2 meters by 2100, “no more, no less.” And while NOAA’s prediction of anywhere between 8 inches and 6.6 feet is a wide rage, they mostly refer to their “intermediate-low scenario” based on projected ocean warming of a 1.6 foot rise. (Which, by the way, is no small obstacle. A recent study published in the journal Nature suggests this estimate alone would displace 13.1 million Americans living in coastal cities.)

“You could think of all sorts of ways that we might duck this one,” Richard Alley, a leading expert on glacial ice at Pennsylvania State University and unaffiliated with the study, told The Times. “I’m hopeful that will happen. But given what we know, I don’t think we can tell people that we’re confident of that.”

But DeConto and Pollard say a rise of five to six feet, the worst-case scenario proposed by NOAA, is a real possibility not to be shrugged off.

“People should not look at this as a futuristic scenario of things that may or may not happen,” Eric Rignot, an Earth sciences professor at the University of California, Irvine, who was not involved with the study, told The Chicago Tribune. “They should look at it as the tragic story we are following right now. We are not there yet… [But] with the current rate of emissions, we are heading that way.”

DeConto and Pollard’s study uses new models to account specifically for Antarctic ice sheets, but they are not the first climate scientists to suggest sea level rise predictions by the IPCC and NOAA are underestimates. Just last week, former NASA scientist James Hansen and 18 co-authors published a study suggesting that serious increases in temperature and sea level will likely occur in decades, not centuries.