Ancient Phoenician DNA suggests a new model of human migration

The Phoenician remains discovered in 1994 provided the first ancient DNA of the Mediterranean civilization that dominated trade routes.

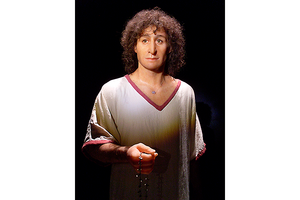

A rendering of a Phoenician man. Researchers have sequenced the first DNA of a Phoenician.

Wikimedia Commons

A 2,500-year-old body discovered in modern-day Tunisia has shaken up researchers’ understanding of the history of human movement.

The remains of the Phoenician – dubbed the “Young Man of Byrsa” or “Ariche” – provided the first ancient DNA of a Phoenician. And an analysis of it found it contains a rare genome previously found only in ancient Europeans, even though Phoenicians are from the Near East, according to research published in PLOS One, the scientific journal, Wednesday.

This discovery is forcing researchers to reconsider the history of human migration, as it was previously thought Near-Eastern farmers replaced European hunter-gatherers.

“Some of [the hunter-gatherers’] lineages may have persisted longer in the far south of the Iberian Peninsula and on off-shore islands and were then transported to the melting pot of Carthage in North Africa [through] Phoenician and Punic trade networks," said Lisa Matisoo-Smith, the study’s co-leader and a biological anthropologist at the University of Otago in New Zealand, said in a statement.

“This is the earliest European lineage recorded in North Africa, so in a way it not only helps us understand Phoenician history, but also makes people [re]think about the history of human mobility,” Matisoo-Smith said to the Independent. “In reconstructions of genetic variation in the Mediterranean, there hasn’t been much consideration of Phoenician trade networks and the likelihood of people moving long distances and spreading those genetic markers widely.”

Discovered in 1994 by gardeners in a sarcophagus near the National Museum of Carthage in Tunisia, the remains of “Young Man of Byrsa” offer a clearer picture into a civilization historians consider one of the great early Mediterranean civilizations.

The Phoenicians are said to have dominated the trade routes of the Mediterranean, according to the study. Originally from Lebanon, they expanded across the sea, bringing with them their highly-prized purple dyes and alphabet. They established cities in Carthage just outside modern Tunisia’s capital of Tunis, as well the ancient cities of Tyre, Sidon, Byblos, and Arwad in Lebanon and southern Syria. There is clear evidence that the Phoenicians reached the Atlantic coasts of Spain and Morocco, and they may even have circumnavigated all of Africa.

However, not much is known about them outside of the accounts of the Greeks and Romans that conquered them, as the history the Phoenicians wrote on papyrus disintegrated. Phoenicians are thought to be of Lebanese descent. But, the “Young Man of Byrsa” complicates this assumption.

The ancient DNA of the “Young Man of Byrsa” indicates he belongs to a rare European haplogroup – a genetic group with a common ancestor. Researchers trace his lineage to the northern Mediterranean, most likely to the Iberian Peninsula of Spain and Portugal. U5b2c1 – the haplogroup – is almost nonexistent in modern times, but has been found in ancient remains in the northern Mediterranean and central Europe.

The scientists involved in the study expected to find DNA of indigenous North African lineage, or from the Near East, reported the Independent.

In addition to confounding these assumptions, the discovery offers a different narrative about northern Mediterranean migration into North Africa, as the Phoenician remains predate the Moorish expulsion from Iberia by about 2,000 years later, according to the study.

However, the researchers note that studies of the ancient DNA of Phoenicians are ongoing, and expect to make further progress in unraveling this genetic mystery.