Mars had explosive volcanoes? What the Curiosity rover just stumbled upon

Curiosity, the NASA rover, has found evidence of silica-rich minerals on Mars, suggesting more sophisticated volcanic processes than previously known.

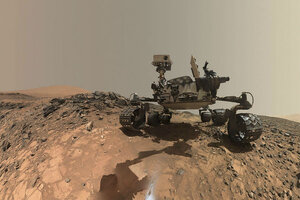

The Curiosity Rover, shown in this August 5, 2015 selfie, used shot X-rays into a mudstone in Mars's Gale Crater and discovered a mineral associated with silica-rich volcanic activity.

NASA/Reuters/File

NASA's Curiosity rover has discovered evidence of silica-rich volcanic materials, a development that has surprised scientists and contradicted previous thinking about the planet's volcanic processes.

In a sedimentary rock in Gale Crater, Curiosity found high concentrations of a mineral called tridymite (SiO2), a cousin of quartz that crystallizes at low pressures and high temperatures.

High-silica magmas form under very different circumstances from the much more common basaltic magmas, so this presents the first mineralogical evidence of these kind of super-explosive volcanoes on Mars.

The Curiosity rover has been exploring Gale Crater since 2012, where it has found evidence of environments friendly to life, including signs of a series of long-lasting lakes. Curiosity explored a region called Marias Pass last year and used its CheMin instrument that shot X-rays into a mudstone. The researchers studied the way the X-rays scattered and determined the existence of tridymite.

Richard V. Morris, the study's lead author and a geochemist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, tells The Christian Science Monitor that scientists have known for decades that Mars had basaltic volcanoes, with fluid lava that lays flat to the ground, similar to the volcanoes found on Earth in Hawaii.

However, tridymite is formed in silicic volcanism, seen on the west coast of the United States at volcanoes such as at Mount St. Helens. The magma feeding these volcanoes has very high silica content and melts at a high temperature, Dr. Morris says. The high-silica magma is very viscous (thick and slow-moving) and builds up inside the volcano, with rising and rising pressure, until a critical point is reached and the volcano explodes outwards.

"All the volcanoes we're aware of on Mars are basaltic, like the Hawaiian-style volcanoes," Morris says. "If the tridymite is from a volcano, it would be more like the ones on Mount St. Helens, which erupt explosively. We don't see any evidence of that in imagery at the president time."

On Earth, high-silica volcanism is tied to plate tectonics, which explains why these types of volcanoes are seen on the west coast, where two plates meet. However, scientists have yet to find compelling evidence of plate tectonics on Mars, Morris says, raising further questions about the origins of the tridymite.

"On Mars, we don't see any evidence of this type of high silica volcanism, so that's a bit of a puzzle," he says.

Given how thin Mars's atmosphere is, even basaltic eruptions could easily produce towering columns of ash. So what would that mean for a differentiated, silica-rich, explosive volcano?

"Maybe we just don't know what the style of that type of volcanism looks like on Mars," he says.

The discovery doesn't provide definitive evidence of explosive volcanoes on Mars, Morris cautions. Mars could have a unique geological process that creates tridymite in a way that doesn't happen on Earth.

His colleagues did model a multi-step chemical process to build tridymite from other minerals, such as high temperature alteration of silica-rich residues of acid sulfate leaching, although they concluded that such a complicated process is less likely than silicic volcanism.

Morris said the finding will stir more research on the topic.

"It would turn people's thinking around quite a bit if it can be shown that there is silicic volcanism on Mars, as evidenced by the tridymite," he says. "There will be a lot of research now to look into geologically credible ways to form tridymite, particularly at lower temperatures and in basaltic environments."