Hold the phone – aliens might not call us back for 1,500 years

A new paper argues that we might not hear back from any alien life forms for up to a millennium and a half, based on how little of the universe has been touched by Earth's radio transmissions.

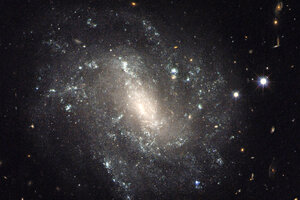

This image provided by NASA shows a barred spiral galaxy 130 million light-years away. If there is intelligent life in our universe, humans likely have to wait at least 1,500 more years to hear back, according to a new study.

NASA/AP

So much for UFOs. Extraterrestrial life might be out there, according to scientists at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., but it is unlikely that our cosmic neighbors will get in touch for at least 1,500 years.

We shouldn't be worrying about how long we wait, say the scientists behind a new paper, "A Probabilistic Analysis of the Fermi Paradox." Chances are that any "messages" the Earth has sent out into the universe in the form of TV or radio signals have likely only reached a tiny fraction of the universe: 0.125 percent of the Milky Way Galaxy, to be precise.

Experts dispute when the first television or radio broadcast strong enough to make it into outer space was broadcasted, with some arguing that the first representation that extraterrestrial beings might have of life on Earth could be the face of Hitler during the 1936 Berlin Olympic games, says Steve Shostak of SETI.

Regardless, humans have been sending out high frequency radio waves since at least Word War II. So if there's something out there, why hasn't it picked up the (metaphorical) phone by now?

"In the case of the Earth, the argument here is, they need to know we're here," Seth Shostak, a senior astronomer at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) who is unaffiliated with the Cornell project, tells The Christian Science Monitor. "How long have we been sending signals into space? If they're more than 70 light years away from Earth, they don't know that there's some sort of intelligent species there."

One of the paper's authors, Cornell undergraduate Evan Solomonides, presented his research yesterday at the American Astronomical Society's meeting in San Diego, Calif. Mr. Solomonides co-authored the paper with Yervant Terzian, Cornell's Tisch Distinguished University Professor of Astronomy.

Mr. Solomonides was inspired to examine the question of "why haven’t we heard back yet" during a class taught by Dr. Terzian at Cornell. He performed a statistical evaluation based on two separate ideas, the Fermi Paradox and the Mediocrity Principle, to come to his 1,500 year prediction.

The Fermi Paradox itself asks why we haven't "heard back" – despite the lack of evidence for extraterrestrial intelligence, it is highly likely, considering how many of the universe's untold billions of planets are probably similar to Earth and could host life. The Mediocrity Principle, which was developed centuries ago by Copernicus, states that with so many other planets, Earth is unlikely to be unique in its capacity to support life. To aliens, in other words, Earth is likely just another watery, rocky planet.

In about 750 years, signals from Earth will have reached 25 million stars, SETI's Dr. Shostak says, a far greater portion of the universe than is currently within range. Considering that there will be about a 750 year return trip for any message aliens might want to send us, we really shouldn't worry about not hearing anything for another 1,500 years or so.

"It's possible to hear anytime at all, but it becomes likely we will have heard around 1,500 years from now," Solomonides said in a Cornell press release. "Until then, it is possible that we appear to be alone – even if we are not."

Solomonides told the Monitor that he believes one of the most important messages to draw from this study is the need to push forward, and not give up for lack of evidence. In order to do so, people need to keep funding the organizations and institutes that make that search possible, no matter how pointless it seems, he says.

"If we ever stop funding the SETI institute, if we stop funding NASA, if we stop funding astronomy and physics, then maybe we'd miss it," he tells the Monitor. "We need to keep trying."