Life on Titan? Look in the tidal pools, say scientists

Models show that the methane oceans on Saturn's largest moon, Titan, could yield the basic preconditions for life due to its hydrogen cyanide, which can help build amino acids and nucleic acids.

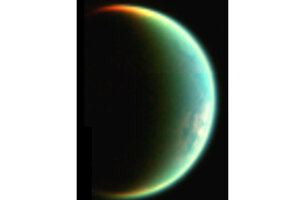

Computer models show that the methane oceans on Saturn's largest moon, Titan, could yield the basic preconditions for life.

NASA

The search for life is leading scientists to Titan, a moon of Saturn that hosts a mix of chemical compounds surprisingly friendly to life, with or without the possibility of water.

Titan hosts a "water cycle" of liquid methane, complete with rivers and lakes that are replenished via rain showers that make Saturn's largest moon "seem like an equally familiar and alien location," as Charles Choi writes for Space.com. To all these features that resemble those of Earth, researchers from Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., have added another possibility – chemical suitability for life.

Researchers theorize that methane oceans, combined with the moon's dense, yellow atmosphere of nitrogen and gaseous methane and synthesized by sunlight, could yield a chemical soup with the basic building blocks of life, what researchers called "prebiotic conditions." Their findings were published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The result of that synthesis is hydrogen cyanide, a highly toxic but carbon-containing chemical abundant in Titan's atmosphere, Space.com reported. Using a computer model, researchers found the chemical can react to form long chains of polymers called polyimine. These make up the most basic components of amino and nucleic acids and could, under the right conditions, become precursors to protein and DNA, particularly in "tidal pools" along the shorelines.

That would make Titan "a test case for exploring the environmental limits of prebiotic chemistry and addressing the question of whether life can develop without water," as the team writes in their study.

"We are not saying we created Titan life in a computer, or even structures that might be in life on Titan," Jonathan Lunine, a planetary scientist at Cornell who worked on the models, told Space.com. "We are saying that the early steps toward structures, catalysis, and absorption of energy might be possible on Titan with polymers like those we modeled."

Other, more typical building blocks for life could already be in place on Titan as well. Data from NASA's Cassini spacecraft has also suggested the moon may have liquid water, as well as methane rivers, but not at the surface. Beneath Titan's icy shell, the probe detected 30-foot-wide tides bulging out of the moon due to Saturn's gravitational pull. If the moon were solid rock, these bulges would likely stretch to only three feet wide, the researchers said.

"Cassini's detection of large tides on Titan leads to the almost inescapable conclusion that there is a hidden ocean at depth," Luciano Iess, the paper's lead author and a Cassini team member at the Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, said in a NASA release. "The search for water is an important goal in solar system exploration, and now we've spotted another place where it is abundant."

As counterintuitive as the idea of life on planetary moons may seem, Titan is not the first to intrigue scientists with the possibility of water – and life, as The Christian Science Monitor's Corey Fedde wrote last month:

The idea has been floating around scientific minds for more than a decade: beneath the icy surface of the Jovian moon could slosh a deep, wide ocean with the perfect environment for life to develop. . . .

Essentially, NASA scientists have modeled the proposed ocean and found Europa's ability to produce oxygen and hydrogen is comparable to Earth's, a sign that the moon could have available energy for life. And the method of producing that oxygen and hydrogen could be totally different from the process on Earth.

Scientists speculate Europa achieved the right compounds in the proper ratio for water through radiation and chemical reactions with the moon's rocky crust, rather than resulting from a volcanic eruption.

Understanding both moons in the context of the search for life outside Earth requires a shift in the scientific approach to biology, researchers said.

"We are used to our own conditions here on Earth. Our scientific experience is at room temperature and ambient conditions," Martin Rahm, a postdoctoral researcher in chemistry and lead author of the new study, said in a press release. "Titan is a completely different beast. So if we think in biological terms, we’re probably going to be at a dead end."