Breakthroughs arise from a precise mix of old and new knowledge, say scientists

Analysis of millions of studies and patents found that the most influential science draws a clear line to the work of previous generations of scientists, a pattern that was 'nearly universal in all branches of science and technology.'

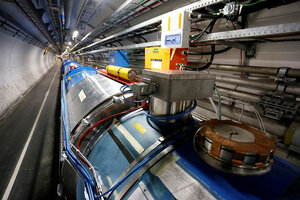

A general view of the Large Hadron Collider experiment during a media visit to the Organization for Nuclear Research in the French village of Saint-Genis-Pouilly, near Geneva in Switzerland in 2014.

Pierre Albouy/Reuters

"If I have seen further," wrote Isaac Newton in a 1676 letter to Robert Hooke about studying the nature of light, "it is by standing on the shoulders of giants." Now, a study of nearly 30 million research papers and more than 5 million patents offers clues as to where more of these giants might be lurking.

A paper published by researchers at Northwestern University's Institute on Complex Systems in the journal Science Advances on Wednesday reveals that the most-cited papers rely on a specific mix of old and new research that the authors say is "nearly universal in all branches of science and technology."

The study addresses a question that lies at the heart of the scholarly enterprise: Today's research constitutes the basic building blocks for tomorrow's discoveries, but what should the composition of those blocks be? The findings point to ways to improve how researchers can assemble the richest combination of knowledge on a topic, and may also reveal deeper patterns in how humanity acquires knowledge.

"We're very interested in trying to understand where knowledge comes from, particularly breakthroughs – these insights in science and technology that are the ones really move the needle in terms of people's thinking," says Brian Uzzi, a professor at Northwestern's Kellogg School of Management and a co-author of the paper.

To find out, the researchers gathered data on citations. "What do scientists and scholars do when they start a new project or work on a new idea?" asks lead author Satyam Mukherjee, now a professor at the Indian Institute of Management Udaipur. "The first thing we do is to perform a literature review and look for related works in the past and also in recent times."

The researchers examined all 28,426,345 scientific papers in the Web of Science, an indexing service for research papers in the sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities, from 1945 to 2013, and all 5,382,833 US patents granted between 1950 and 2010. They found that the papers and patents with the highest impact, defined as garnering the top 5 percent of citations in their field, tended to cite relatively new information, but with a long, diminishing tail into past work.

"Our research indicates that one needs to see the entire arc of a given idea or concept over time to use it most effectively in one's own work," says Professor Mukherjee.

The researchers were surprised by their findings' universality. The sweet spot – or "hotspot," as the researchers call it – between old and new research held for papers in physics, gender studies, and everything in between, from the postwar era to the present.

"I was expecting that the patterns would vary drastically by time period and academic field," says mathematician Daniel Romero, now an assistant professor at the University of Michigan's School of Information, who worked on the study as part of a postdoctoral fellowship at Northwestern. "After all, different fields have different norms for how they cite other work."

The findings address what philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn famously called "the essential tension" between tradition and innovation in scientific research. "It says something very deep about where you want to look for information," says Professor Uzzi. "And also something very deep about how knowledge itself matures through time."

Mark Hannah, an assistant professor in Arizona State University's English department who specializes in cross-disciplinary communication in the sciences, suggests that the hotspot may emerge from efforts to reconcile new modes of thought with older ones.

"You're seeing a balancing between legacy language and emerging language," says Professor Hannah, who was not affiliated with the study. "They're doing the work of thinking how those studies come together."

The study's authors also found that scientists who worked collaboratively were more likely to rely on research within the knowledge hotspot than those who worked alone, a finding that came as no surprise to Anita Woolley, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University's Tepper School of Business who specializes in collective intelligence. "Having a team work on it is what leads them to cite the sufficient variety of references," she says "If you have a team you are more likely to have a diversity of different knowledge and perspectives."

"When you're working with collaborators, you're forced to explain yourself more," says Hannah. "You're forced to think through and anticipate how your use of language may not be well understood or may create a barrier for readers."

The findings may point to ways to improve the technology that scientists and other scholars use to search for information, an increasingly pressing need amid what Uzzi calls the "absolute explosion in the amount of information that's created every single day."

Professor Woolley mentions Google Scholar, a free search engine for academic publishing whose slogan is: "Stand on the shoulders of giants."

"Usually they give you some mix of what's the highest cited but also what's recent," says Woolley. "Definitely it tends to make the rich get richer in the citations race, because they come up first. But it also probably biases you toward fairly recent things as well."

The discovery of this hotspot may point to ways search engines could be improved: "Imagine if you were to develop a search engine that could deliver information in a way that it grabs this hotspot of knowledge," says Uzzi. "And if you can do that, you'd be pointing people from the get-go to the place in the store of knowledge where they are most likely to find the building blocks of tomorrow's ideas. That would solve a tremendous amount of wasted-time problems."

But Sidney Redner, a physicist at the Santa Fe Institute who specializes in citation statistics, cautions that the correlations uncovered by Mukherjee and his colleagues, which he calls a "cool observation," could be misconstrued. "I think there's potential for misuse of this kind of stuff," he says, noting that researchers often cite papers for the purpose of refuting them. "There's no contextual information in citations."

"That's what worries me about the whole field of citation studies is that it gets misused by administrators," says Professor Redner. "If I were trying to use this as a tenure-decision mechanism, I would be very worried."

Leveraging the power of the hotspot offers may require researchers be more mindful in supplying such context to their citations.

"It comes back to us as scholars and us as researchers to be clear about the ways we conduct our research and the ways that we use our sources, so that we are making visible our selections and our rationale, so that we don't become subject to an algorithm," says Hannah. "It's challenging work, but it's something we're prepared to do."