Neutrino demonstration heralds a new way of observing the cosmos

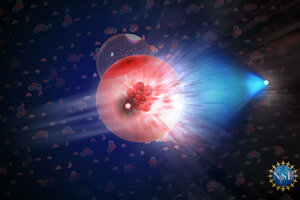

In this illustration, a neutrino has interacted with a molecule of ice, producing a secondary particle – a muon – that moves at relativistic speed in the ice, leaving a trace of blue light behind it.

Courtesy of Nicolle R. Fuller/NSF/IceCube

On September 22, 2017, a shock wave of blue light flashed through the crystal-clear glacial ice a mile beneath the South Pole, heralding an entirely new way of looking at the universe.

The light arose from the collision between a remarkably energetic neutrino – a wraithlike subatomic particle moving close to the speed of light – and the nucleus of a hydrogen or oxygen atom deep within the ice. The IceCube Neutrino Observatory, an array of more than 5,000 basketball-sized sensors suspended thousands of feet beneath the surface, detected the flash and then reconstructed the neutrino’s path.

According to research published Thursday in the journal Science, IceCube sent out alerts to more than a dozen observatories around the globe, directing their attention to the region in the sky where the neutrino was thought to have originated.

Why We Wrote This

Compelling evidence that an ultrahigh energy neutrino originated in a blazar some 4 billion light-years away shows how astronomy can be done using an entirely different kind of particle.

There, about 4 billion light years from Earth, they saw a familiar object. TXS 0506+056, as it is known, is a blazar, a giant elliptical galaxy with a supermassive black hole spinning at its core. As it devours material around it, the black hole spews twin jets of particles moving at hundreds of millions of miles an hour, with one of those jets aimed in Earth’s direction. The event marked the first time scientists have identified the likely origin of a neutrino from beyond our solar system.

“It’s a demonstration that neutrinos can do astronomy,” says Naoko Kurahashi Neilson, a physicist at Drexel University in Philadelphia and a member of the IceCube team. “We’ve been talking about neutrino astronomy for 10 years, but it’s hard to be taken seriously when you haven’t even seen anything definitively from outside the solar system before.”

From the ancient Babylonians through Galileo up through the mind-bending breakthroughs of the 20th century, the history of astronomy has been defined largely by one particle, the photon. All the light in the sky, from the distant stars and nebulae to the sunlight reflecting off the planets, moons, and other celestial bodies, arrives at our eyes, photographic plates, and camera sensors in the form of these subatomic packets of energy.

Beginning in the late 19th century, astronomers began observing invisible wavelengths, from radio waves to gamma rays, bands on the electromagnetic spectrum that are determined by the amount of energy their photons carry. Observing these photons led to startling discoveries about our cosmos, from the Big Bang to the existence of dark matter.

Neutrinos, which originate in the sun, the Earth, and even from the radioactive decay of elements in our own bodies, as well as from sources outside our galaxy, are vastly more abundant than photons. But they are incredibly harder to detect. About 100 trillion of them pass through your body each second, say scientists. They are believed to have a mass of less than one millionth of that of an electron and no electrical charge, so they travel unhindered and unnoticed, often for billions of light-years.

Neutrinos stop when they collide with a proton or neutron in an atom’s nucleus. But, because neutrinos are so small and because atoms are almost entirely empty space – if the nucleus of an atom were the size of a grape, the electrons would orbit at an average distance of about one mile – such collisions are rare.

This is Antarctica calling

Completed in 2010, the IceCube observatory at the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica aims to capture these exceptional encounters between neutrinos from beyond our solar system and atomic nuclei. On average, this occurred once every eight weeks or so in the nineteen months before this particular neutrino was detected.

When that happened, observatories around the world, from an optical telescope in the Canary Islands to a gamma-ray observatory orbiting hundreds of miles above the Earth, leapt to action. One of the two papers published Thursday in Science on the findings involves 16 teams comprising more than 1,000 scientists.

“I can’t remember a time when so many instruments came together to work on a single science case,” says Reshmi Mukherjee, a physicist at Barnard College and a member of the VERITAS observatory, a gamma-ray telescope in Southern Arizona that helped pinpoint the likely source of the neutrino.

“The popular image of the lone astronomers is, I’m afraid, out of date,” says Dawn Williams, a particle astrophysicist at the University of Alabama and a member of the IceCube team. “Science is definitely moving in the direction of more collaboration, larger collaboration, and collecting large data sets.”

Recent years have seen astronomy begin to broaden beyond the photon. In 2016, scientists using data from the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory in the United States said they had detected ripples in the fabric of spacetime produced by a black hole collision some 1.3 billion light-years away. It was the first of several observations of gravitational waves that would earn its principal theorists the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics.

By observing neutrinos, astronomers hope to peer farther into the cosmos than they can with photons. Professor Mukherjee says that photons from high-energy sources tend to get absorbed by infrared background radiation. Neutrinos, by contrast, “don’t get absorbed by this fog of low energy light,” she says, “so they basically have this the best quality in terms of going back directly to the source.”

“Maybe there are sources out there that we can’t see in any other ways other than neutrinos,” says Professor Neilson. “We have no clue what the universe looks like in neutrinos yet.”