From Einstein to Duchamp: the physics of modern art

The ‘Dimensionism: Modern Art in the Age of Einstein,’ exhibit features 20th-century artists who drew inspiration from physics. Displayed works include Anton Prinner’s 1932 ‘Colonne’ (r.) part of the Mead Art Museum’s permanent collection, and Pablo Picasso’s 1917 ‘Young Girl in an Armchair’ (l.) on loan from the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky. (© 2018 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York).

Courtesy of the Mead Art Museum

A free exhibition at the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College takes its inspiration from a figure not usually associated with the arts: Albert Einstein.

“Dimensionism: Modern Art in the Age of Einstein,” which opened at the Mead on March 28 and runs until July 28, includes about 70 works from an array of early 20th-century artists. These include gently rotating mobiles by the American sculptor Alexander Calder, spinning paper discs by the French avant-garde artist Marcel Duchamp, and colorful depictions of life on a microscopic slide by the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky.

At first blush, these artists seem to have little in common. But their names all appear, along with other famous artists, on the 1936 Dimensionist Manifesto, a call for writers, painters, and sculptors to transcend their static Newtonian framework and embrace a dynamic conception of the cosmos.

Why We Wrote This

Science and the humanities are often viewed as intrinsically separate. But when it comes to abstract physics, the arts have served as a tangible forum to explore scientists’ ever-shifting depictions of reality.

The exhibition challenges the narrative that Western culture is split into two cultures, science and the humanities, says Vanja Malloy, the Mead Museum’s curator of American art and the exhibition’s organizer.

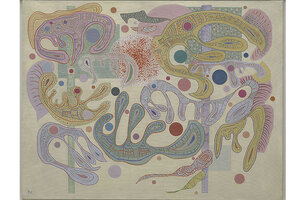

“It shows us, at least on one side, that’s not true,” she says, gesturing to Kandinsky’s 1937 oil-on-canvas painting, “Capricious Forms.” “Here, you have artists with microscopes.”

Many of the artists were influenced by Einstein’s revolutionary ideas about space and time. Others were inspired by mathematical conceptions of a fourth spatial dimension, the hidden world revealed by X-rays, and the fuzzy and indeterminate reality proposed by quantum theory.

“Both art and science challenge our idea of what we see as reality,” says Dr. Malloy. “And science is something that informs our worldview whether or not we like to admit it.”

Drafted by the Hungarian poet Charles Sirató, the Dimensionist Manifesto states that “[w]e must accept – contrary to the classical conception – that Space and Time are no longer separate categories ... and thus all the old limits and boundaries of the arts disappear.”

The manifesto called all forms of art to explore the next dimension – for lines of text to become planes, for paintings to step into cubic space, and for three-dimensional sculptures to move. The exhibition, which opened at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in November and traveled to Amherst last month, includes paintings, sculptures, mobiles, visual poetry, and three short films.

One of Dr. Malloy’s favorite works in the exhibition is titled “Study for Lobster Trap and Fish Tail,” an arthropodal mobile by Calder consisting of several plates of painted sheet iron that sway gently in response to people entering and leaving the room. Like subatomic particles in the quantum mechanical model, it seems impossible to observe Calder’s mobile without influencing it.

And yet, for all of his abstract renderings, Calder identified himself as a realist, notes Dr. Malloy. “The universe is real but you can’t see it,” said Calder in a 1962 interview. “You have to imagine it.”

Linda Dalrymple Henderson, an art historian at The University of Texas at Austin, notes that the Dimensionist Manifesto drew together artists with very different ideas about what the fourth dimension actually was. The first group, whose artistic sensibilities formed before Einstein’s theories became widely known, thought of the fourth dimension as a spatial construct. This was a logical extension of the transition from two to three dimensions that was developed by mathematicians in the 19th century.

“The idea of a special fourth dimension is such a liberating one for artists,” says Professor Henderson. “It’s not surprising that styles like cubism developed, because all bets were off in terms of space and matter.”

Professor Henderson places Pablo Picasso, whose 1917 work “Young Girl in an Armchair” appears as part of the exhibition, in this first group, calling the widespread assertions that the artist was influenced by Einstein a “myth.”

But after 1919, when Einstein became a household name after data from an eclipse supported his theory of general relativity, the art world’s conception of a fourth dimension shifted.

“Truly the coming of Einstein in 1919 is a huge shock for any artist,” says Professor Henderson. “This notion that people’s basic ideas about space and time and measurement of distance are wrong, it’s pretty earth shaking. That has a huge impact on artists, who are like barometers. They just are so sensitive to the newest ideas.”

Under this newer conception, the fourth dimension is temporal: According to Einstein’s theories of relativity, the four dimensions together constitute spacetime, a single manifold that links “where” with “when.”

Artists in this camp tended to represent the fourth dimension as movement, such as Calder’s mobiles or Duchamp’s spinning discs. “That next younger generation,” she says, mentioning Calder, “is ready to just embrace notions of the fourth dimension primarily into time and explore them in kinetic art.”

“Charles Sirató was such a brilliant thinker,” says Professor Henderson, for his ability to identify an artistic community out of these two seemingly disparate camps.

But Sirató was hardly alone in recognizing the potential of 20th-century physics to revolutionize art. As Lynn Gamwell, a lecturer in the history of art, science, and mathematics at the School of Visual Arts in New York, points out, several other manifestos appeared in the years following Einstein’s 1919 rise to fame.

“The art world is full of science,” says Dr. Gamwell. “Art expresses how we understand reality, and we understand reality in a scientific worldview today.”