K2 mission confirms 104 new alien planets

Confirmed exoplanets are still pouring in from Kepler data, even after the 2013 malfunction that led to the rebooted mission, K2. The spacecraft has now added over a hundred more confirmed exoplanets to its impressive exoplanet hunting resume.

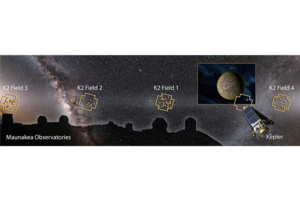

This image montage shows the Maunakea Observatories, Kepler Space Telescope, and night sky with K2 Fields and discovered planetary systems (dots) overlaid. An international team of scientists discovered more than 100 planets based on images from Kepler operating in the ‘K2 Mission.' The team confirmed and characterized the planets using a suite of telescopes worldwide. The planet image on the right is an artist’s impression of a representative planet.

Courtesy of Karen Teramura/University of Hawaii/Miloslav Druckmüller/Shadia Habbal/NASA

When it comes to spotting alien worlds, NASA's Kepler spacecraft takes the proverbial cake. Data from the craft is responsible for the discovery of more than 2,000 confirmed exoplanets.

And it doesn't seem to be slowing down in its second mission, dubbed K2. The K2 research team has just validated 104 more exoplanets, some of which show tantalizing signs of habitability.

This continued success suggests the 2013 malfunction that temporarily took Kepler out of commission was just a hiccup. Now scientists predict that 500 to 1,000 new exoplanets will be discovered over the course of K2's planned four-year mission, according to a paper published Monday in the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series announcing the newly confirmed exoplanets.

The Kepler and K2 research team carefully cross-examined 197 planet candidates spotted during the first year of the reboot mission. Among those candidates, they identified 30 false positives and 63 candidates that still need more research to determine their status.

Some of the newly validated exoplanets could be rocky planets, like our own. There are four potentially Earth-like exoplanets, all between 20 and 50 percent larger than Earth, that the scientists find particularly intriguing.

These four exoplanets all orbit the same star, which is dimmer and less than half the size of our Sun. With orbital periods of 5.5 days to 24 days, these exoplanets orbit more tightly around their star than even Mercury around the Sun (at 88 days). But two of these alien worlds could be experiencing similar radiation levels from their dimmer star as the Earth does from the sun, according to the scientists' analysis.

Despite the differences in this system to our own solar system, there could still be conditions conducive to life on these exoplanets, said Ian Crossfield, lead author of the paper and a NASA Sagan Fellow at the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

"Because these smaller stars are so common in the Milky Way, it could be that life occurs much more frequently on planets orbiting cool, red stars rather than planets around stars like our sun," Dr. Crossfield said in a W. M. Keck Observatory press release.

K2 may be better suited to investigate that type of stellar system than the original Kepler mission.

Kepler initially focused on just one section of sky in the northern hemisphere in its hunt for Earth-like exoplanets, but when the second of the spacecraft's four reaction wheels failed in May 2013, it could no longer point precisely at the original target area.

But the research team didn't let Kepler go to waste. Instead, they rejiggered the spacecraft so it could harness the pressure of sunlight to stabilize itself, thus launching the K2 mission.

This new setup actually covers more of the sky, with a sweeping ecliptic field of view. This means that the spacecraft gets a broader view of the Milky Way, which has more smaller, cooler, red-dwarf type stars than sun-like stars.

"The K2 mission allows us to increase the number of small, red stars by a factor of 20, significantly increasing the number of astronomical 'movie stars' that make the best systems for further study," Crossfield said in a University of Arizona press release.

Both missions employ the "transit method" to identify exoplanet candidates, noting when the brightness of a star dips just as if an orbiting planet passed in front of it. These discoveries are confirmed as exoplanets by combining Kepler data with ground-based observations from telescopes such as the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, the twin Gemini telescopes in Hawaii and Chile, the Automated Planet Finder of the University of California Observatories, and the Large Binocular Telescope operated by the University of Arizona.

"This bountiful list of validated exoplanets from the K2 mission highlights the fact that the targeted examination of bright stars and nearby stars along the ecliptic is providing many interesting new planets," Steve Howell, project scientist for Kepler and K2 at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, said in the University of Arizona press release. "This allows the astronomical community ease of follow-up and characterization, and picks out a few gems for first study by the James Webb Space Telescope, which could perhaps provide information about their atmospheres."