Third-grade math: a teacher’s calculus

Reconciling diverse languages, experiences, and the playfulness common to all 9-year-olds, Ann Griffith's job is to get her students to the right answers.

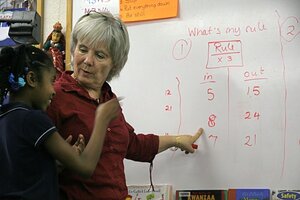

Math ins and outs: Ann Griffith works on multiples of 3 with third-grader Emani Brown.

Mary Wiltenburg

Decatur, Ga.

Some of her kids can multiply dozens; some are still adding on their fingers. Some, by Georgia standards, are failing third grade math. But today, whatever Ann Griffith's students know about division, they're fired up about it.

A dozen 8-to-10-year-olds sit cross-legged on the carpet of her trailer classroom, around their small, feisty teacher and the large rectangular white board on which she's written:

Rule:

x3

in | out__| 15

"Who can tell me?" Ms. Griffith asks.

A girl with wheels in her sneakers shoots a hand into the air. A curly haired boy looks lost. To one side, a kid whose contraband calculator Griffith confiscated a moment ago is looking around for fresh mischief. And from the vicinity of Griffith's right foot, someone is squeaking.

"Ooh!" says Erin Harris, "Ooh, ooh!"

Since school began in August, Erin, a dedicated writer and artist, has been fearful of math. This winter morning, there are pushier students on the floor with their hands up, and kids likelier to get the problem right. There are hungry kids, distractable kids, kids whose families are suffering in this economy; 67 percent of students at the International Community School Erin attends receive free or reduced-price lunches. Half of the 400 students at the public charter school outside Atlanta were born overseas; many came to the US as refugees and are struggling to master English. Erin's not.

She's just sitting on the carpet, hand in the air, unaware in her excitement that her torso and arm now form a 60-degree angle with the floor, bent by the force of an answer she's sure she knows.

Griffith has a split second to calculate all of this and decide - in light of nearly two decades' experience teaching in schools across the globe and four months getting to know these 12 students - whose name to call. It's a problem with countless variables and no perfect solution. At this moment, Griffith reckons, Erin is the one in this third-grade math class who most needs to be right.

"Erin is bursting," she says.

"Five!" says Erin triumphantly.

"That's right," Griffith says, filling in the answer on the board. "Now, how did you figure that out?"

"I knew it." Erin can't articulate what classmates leap to explain: She could have gotten the answer counting up by fives, or dividing three into fifteen. She's not there yet.

But today, for the first time, Erin knows her threes. And it feels marvelous.

"You just knew it," says Griffith solemnly, "Isn't that cool?"

"Yeah," says classmate Ross Wills, who mastered his times tables this fall, "she knows them by heart."

It's a pause, a breath in the lesson, to acknowledge Erin's breakthrough. But Griffith can't stop there. Because gears are turning in 10 other heads, and now Mateo Tewari, the curly haired kid who looked so lost a moment ago, has his hand in the air and wants to know: What if you had 4 plus 4 plus 4 plus 4? Would that be multiplying?

How do you teach third-grade math? Most of us, who learned it ourselves, assume we know. But a public school classroom today, especially at a school like ICS, is one of the most diverse places you can go in modern America. Nationally, the No Child Left Behind act has transformed the way students, teachers, and schools are evaluated. Former President George Bush signed the act into law in 2002 with the words: "I can't think of any better way to say to teachers, We trust you.' " Many teachers say it feels like anything but - and that's having an impact on their teaching. The rules have changed.Last spring, ICS - the community-focused, kid-driven haven of a charter school where Griffith teaches and Bill Clinton Hadam studies - failed to meet its test score requirements under No Child Left Behind. Now ICS, like many schools across the country, is struggling with what that means - and with the limits of standardized tests to describe what's going on in their classrooms.

This week, our series will look, in three stories, at how a veteran teacher handles a single day's math class, leaving no child behind while holding none back; what "failure" can mean under "No Child"; and how hard it is to gauge academic progress in English learners.

Griffith is a warm, irreverent Welsh woman with short gray hair, an obvious affection for her students, and no time for official nonsense. For 17 years, 10 of them full-time, she's taught third and fourth graders and middle schoolers in international schools in Sri Lanka, the UK, India, and Bangladesh.

Her classroom is a 19-foot by 23-foot box in a prefab building behind the church where ICS rents space. Most of the decorations were made by her students. Over the white board hangs the class rule, colored in by all its students: "RESPECT."

Growing up in Welsh public schools, Griffith says, "I didn't like math. I didn't enjoy it." She wasn't encouraged to analyze why numbers behaved the way they did. Now, her main goal in math is to get students asking, "Why?"

They're doing that this morning, until a scab on one boy's foot begins to bleed. Griffith quickly sends him off with her teaching assistant to find a bandage. But 22 eyes follow him toward the door and excited chatter ensues as kids go up on their knees, ready to break ranks. Chaos threatens.

Griffith barely raises her voice. "If you want to think about that, just look at the color of this marker," she says, brandishing her dry-erase pen and sticking out her tongue.

"Aah!" screams Ross, "It's blood-red!"

With that, they're back to times four.

Griffith's students are all over the map: from early reading to chapter books, from finger-adding to decimals. This is a pivotal year for all of them. By April, they must master place value, multiplication, division, and fractions; have a strong foothold in geometry; and prove these things on a Georgia standardized test - or spend next year in remedial math. If kids don't reach a certain level of math and reading proficiency by the end of third grade, educators say, they're likely to spend the rest of their educational life playing catch-up.

For some of Griffith's kids, this is a real threat. Students came to her speaking English, Somali, Bosnian, French, Kurdish, and Farsi as their first languages. Their home lives, and stages of emotional, social, and intellectual development, couldn't be more different.Griffith, ICS, and Georgia deal with the disparity in student progress in two major ways. First, at 11 each morning, Griffith loses seven students, most with limited English, to a remedial math class across the hall. These kids, like Bill Clinton Hadam in the class next door, failed last year's state tests: Sakinah in her pale blue head scarf, Hassan in his orange hat, and Mita with her irrepressible grin.

Second, Griffith does what she's doing now. Surprised by how engaged the remaining kids are, she alters her lesson plan to let them spend a little more time at the board. There, they help design problems they'll solve back at their seats, armed with dry-erase markers and squirt bottles, in a thrillingly naughty exercise they call: "writing on our desks."

As Griffith makes a new box for "divided by four," someone suggests putting a 2 in the In column.

"You can't do that!" says Ross worriedly. Griffith asks why not. Four is bigger than two, he says, and you need to divide a number by something smaller than it.

While most of their classmates are focused on solving the problems, Ross and a few others are thinking about the parameters for creating them. It's an example of what educators call differentiated instruction: engaging students on multiple levels with the same material.

"It's actually very subtle," Griffith says. "It's little seeds that you're throwing out, and those that can see them pick them up."

It's clear that Griffith's kids are picking them up at their own pace. In the course of the morning, Erin, Mateo, and Ross all have small but significant breakthroughs. Whether these will translate to the tests this spring, though, is an open question.

Last year, half of ICS's 56 third graders and nearly 70 percent of its fourth graders failed the state math exam; as a consequence, their school failed, under No Child Left Behind.

Wednesday: How the strides Bill Clinton Hadam and his school make can still be called failure' by official measures.