How Mary Leakey carved a place for women among man's earliest steps

Google Doodle celebrates the life of renowned British paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey. Leakey, who was born 100 years ago today, gained recognition while working with her husband, Louis Leakey, and thrived long after his death.

Mary Leakey 100th birthday: Celebrated with a Google Doodle today, the famed paleontologist did not slow down her work to parent. She brought her three sons to the dig site as babies.

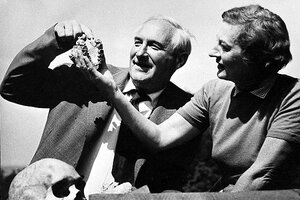

Courtesy of The Leakey Foundation

Today Google celebrates the life of Mary Leakey, a renowned British paleoanthropologist whose discoveries transformed the study of human evolution.

Leakey, who was born Mary Douglas Nicol on Feb. 6, 1913, became known for her groundbreaking findings in Africa: a Proconsul skull that was proven to be a prehistoric ape ancestor, a Australopithecine Bosei skull that dated back to an unprecedented 1.75 million years, and fossil footprints of prehistoric hominids.

Despite her legacy, there are some feminists who characterized Mary Leakey as an under-appreciated woman in a man’s field. They note that her field partner and husband, Louis Leakey, would often present her findings.

Even after her death in 1996, some questioned the Leakey partnership. Ms. Magazine’s brief obituary of Mary Leakey noted that when Louis Leakey gave lectures in the United States, “he gave the impression that he made the discoveries his wife had made.”

But Mary Leakey did not subscribe to the feminism of her time, says Virginia Morell, author of “Ancestral Passions: The Leakey Family and the Quest for Human Beginnings.” She was a strong woman who neither resented her husband for being in the spotlight (in fact, she preferred it that way), nor felt threatened by her male counterparts.

"She didn't feel like she was held back by men," Ms. Morell says. "She didn't view the world that way. She didn't feel that she had been slighted in the field.”

Mary Leakey would never have made those discoveries had she not fallen in love with him and joined him on his digs, which were his idea. But Louis Leakey would never have been as successful either, were it not for her.

Before meeting Louis Leakey, Mary was an illustrator at the Hembury Dig in Devon, England, according to the Leakey Foundation website. She had gained recognition for her depictions of Stone Age artifacts.

Though she never attained a degree, Nicol had audited university classes in archaeology and geology. Yet she felt less confident around her learned counterparts, Morell says.

She met Louis Leakey in 1933 and joined him in Africa to illustrate his findings. They not only ended up doing excavations together, but also fell in love and married in 1937.

As partners, Louis and Mary Leakey complimented each other, Morell says. He had the vision, and she had the meticulousness to carry out his ideas.

“Mary was more diligent about sticking to one thing and sticking it out,” Morell says. “That may have been one reason that, for her more careful approach, she as the one who often discovered things.”

Mary Leakey expected everyone to carry their own weight around. Literally. Morell recalls meeting the researcher in Kenya for the first time in the mid-1980s. Morell was invited to help work on the digs and carried her own dirt off, which she says was how she earned Mary Leakey’s respect.

"She was very impressed that I carried my own dirt, that I hadn't asked her or the men in the dig to carry it for me. She thought I was okay,” Morell says. “In retrospect, I can see why she would like that … She didn’t appreciate girls who played the weakling card.”

Despite her strong personality, Mary Leakey never liked the spotlight, Morell says. In 1948, she discovered the Proconsul africanus skull in 1948, and Louis Leakey asked her to take the credit. Mary Leakey traveled to England to present her findings, but found the press attention daunting.

“Part of it was that she was a very shy person,” Morell said. “She wasn’t trained as an archaeologist in a traditional way, and she realized that.

Louis Leakey went on to give lectures and present their work, including the discovery of the Australopithecine skull from 1.75 million years ago. Meanwhile, Mary Leakey continued the excavations with a team of workers.

After her husband’s death in 1972, Mary Leakey continued her research. She studied at the Laetoli site in Tanzania, where she found the remains of 25 early hominids and 15 new animal species. Among these were the footprints of the Australopithecus afarensis.

In 1969, Leakey received an honorary doctorate from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, followed by several other honorary degrees.

It was after those distinctions, Morell says, that Mary Leakey began to feel more confident with giving lectures and speaking publicly about her work.

“Once she was recognized that gave her the confidence she needed to speak out,” Morell says. “I don't think it had anything to do with her being a woman because Mary … never took a second seat to Louis.”

Mary Leakey did not advocate for women's rights and even disliked the feminists of her time, but she demonstrated the strides women can make in research. She led by example, not by protest. At the end of the day, all Mary Leakey asked for was to everyone, regardless of gender, to carry his or her own dirt.