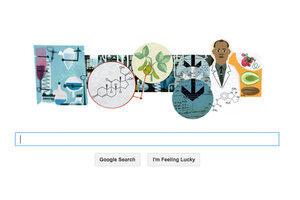

Percy Julian, pioneering black chemist, earns a Google Doodle

Facing immense challenges both in the lab and as a black chemist in a largely segregated America, Percy Julian overcame many barriers in order to produce groundbreaking discoveries. He is honored by a Google Doodle on what would have been his 115th birthday.

Percy Lavon Julian is honored for his groundbreaking chemical discoveries in a Google Doodle.

It's rare that someone who didn’t have education available after eighth grade earns a PhD in chemistry (in addition to 19 honorary doctorates) and holds more than 100 patents.

That is the case, however, for Percy Julian, an African-American chemist who repeatedly overcame barriers in order to develop groundbreaking chemical synthesis. Google honored his pioneering work, and dogged perseverance, through a Google Doodle on what would have been his 115th birthday.

Mr. Julian was born April 11, 1899 in Montgomery, Ala., to a postal worker and a schoolteacher. His grandparents had been slaves. Despite the fact that Montgomery did not offer education for black students after eighth grade, his parents pushed him to continue his education and he was accepted for pre-college studies at DePauw University in Indiana. The college did not accept many African-American students at the time, and Julian faced difficulties throughout his time there. He wasn’t allowed to live in the college dormitories and wasn’t served meals, so he ended up working and living at a fraternity house. These outside factors didn’t affect his studies, however – he graduated as valedictorian and Phi Beta Kappa in 1920.

From there, he went on to teach chemistry at Fisk University in Nashville, and a year later was accepted as the first African-American chemistry masters candidate at Harvard University. The acceptance was only the first challenge, however. While he gained his masters degree in 1923, after continuing to study there for three more years, he was denied a vital teaching assistantship, which was key to keeping him at the university. He taught at a small college in West Virginia, and then was asked to join the faculty at Howard University in Washington, where he earned a fellowship to get his PhD at the University of Vienna in Austria.

Those Austrian labs were the first place that felt free to Julian, and provided the necessary materials to do solid research. This is where he started studying plant alkaloids, which provided the basis for the rest of his life’s work.

Julian returned from Vienna with his doctorate, but quickly ended up embroiled in university politics that resulted in his dismissal from staff. He returned to DePauw, where he galvanized undergraduate research and took on high stakes projects to build up his reputation once again. His main focus was on how to synthesize plants – in other words, artificially create in-demand plant alkaloids by building them molecule-by-molecule. Though he produced some impressive work, no colleges were willing to take on an Africa-American professor. He turned to corporations, and was eventually hired as director of a research lab in Chicago.

It was there that he had his true breakthrough. He worked with soybeans, and lead his team to discover ways to develop a stream of household and manufacturing goods based off of synthesizing plant materials. Julian created an Alpha protein, which became the main ingredient in “bean soup” – a fire-fighting foam that saved millions of lives. He also began working on passion projects on the side, including synthesizing female hormone progesterone, as well as steroids and cortisone, all from soybeans. This had never been done before.

After that, Julian struck out on his own, created Julian Laboratories, which hired many black scientists and researchers who had largely been shut out of mainstream research institutions. Though he had made waves in the chemical world, he continued to face discrimination. He and his family were the first black family to live in Oak Park, Ill., and their house was firebombed twice. He pushed back against racism, however, by remaining in the neighborhood, joining the NAACP, and speaking about his success as an example of what African Americans were capable of.

Though he died in 1976, his perseverance in the face of both immense scientific and social challenges are remembered by many.

“Here was a man who not only had to overcome the disadvantages of his race, but who, throughout his entire life, was in a situation that was never ideal for doing the big things he was trying to do,” says Gregory Petsko, a chemist, in a NOVA special on Julian. “Looking over his life, one has a sense that here is a man of great determination. And it's a determination not just to succeed, but a determination to make a difference, to make a contribution.”