Next generation of cyber defenders prepare for expanding battlefield

While private-sector cybersecurity flaws, such as the recent Microsoft Internet Explorer hack, dominate headlines, college-level cybersecurity competitions have become a major training and recruiting ground to supply the growing cybersecurity need.

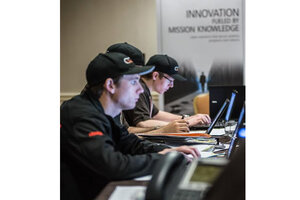

Students compete at the 2014 Raytheon National Collegiate Cyber Defense Competition (NCCDC). The need for cybersecurity has grown rapidly in the past year as high-profile private sector attacks have dominated headlines.

NCCDC

When reigning champion of the Raytheon National Collegiate Cyber Defense Competition (NCCDC) and current Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) senior Lucas Duffey heard about the Target hacks, he could only pity the multibillion dollar company.

“It was kind of sad,” says the computing-security major. “A lot of us look at these things and say ‘Why did that have to happen in the first place?’ ”

Listen up, Target. Mr. Duffey is soon to be the first line of defense against the growing threat of cyber attacks.

The need for an increase in the cybersecurity workforce has been apparent for some time – a 2010 Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) study announced there was a “human capital crisis” in cyber security, with an outstanding need for 10,000 to 30,000 trained workers. While this study and others called for a more robust military cyber defense, this year has caught the private sector on its heels. High profile attacks such as the Target credit card breach, which left more than 70 million cards compromised, and numerous other vulnerabilities have ramped up the demand for high quality cyber defenders. This, in turn, has created a surge of interest in competitions that are recruiting and training the next generation of cyber defenders, one simulated hack at a time.

Welcome to the Final Four of the cybersecurity world.

“[NCCDC] is definitely very stressful,” Duffey says. “Your systems are going down all the time.”

The competition, which has taken place in San Antonio, Texas, every year since 2004, brings 10 universities from regions across the country together for a three-day competition. Each team is put in charge of a fictional small tech company with 50 or more users, 7 to 10 servers, and common Internet services, such as mail servers and e-commerce. Over 17 hours, teams are scored on their ability to keep servers running, respond to customer inquiries (such as “Can you reset my password?”), and balance security with business.

Then there is the Red Team. This is a group of hackers whose sole purpose is to dismantle the other teams’ security by running denial of service attacks and hacking customer passwords.

Duffey says his team practiced for hours every day in the months leading up to the competition, even skipping spring break vacations to learn operating system configurations and researching likely hacker targets. But he says the competitions provide incentive for that sacrifice.

“A lot of material you learn in school is very watered down,” Duffey says. “The great thing about security competitions is that they give you pretty much every challenge you could see in a very short amount of time.... It pushes you to research on your own time.”

Despite its grueling nature, the competition has only become more popular among students and schools. In 2006, 24 universities participated. During the 2014 regional and national competitions, more than 180 universities were represented and more than 2,000 students participated. Sponsors, who range from Goldman Sachs and the US Army to Microsoft (which recently has dealt with a high-level vulnerability with its Internet Explorer browser), heavily recruit student competitors.

That’s because need for trained cyber defenders has skyrocketed since the first NCCDC competition and 2010 CSIS report. Burning Glass Technologies monitors the supply and demand for cybersecurity jobs and found that between 2007 and 2013, cybersecurity job postings grew 74 percent, but postings took 24 percent longer to fill than normal information-technology jobs and 36 percent longer than postings in general.

The private sector discovered its need the hard way. PricewaterhouseCoopers’s 2014 Global Economic Crime Survey found that over the last three years, 7 percent of US organizations lost more than $1 million each to cybercrimes, and 19 percent lost between $50,000 and $1 million.

“This is no longer a back-room discussion, this is a boardroom discussion,” says former Air Force Gen. Harry Raduege, chairman of the center for cyber innovation at Deloitte, a previous top-level sponsor of NCCDC, and co-chair of the CSIS commission. “Frankly, some progress had been made, but there [is] an obvious need for much much more."

General Raduege says there aren’t enough workers that have the combined science, technology, engineering, and math training needed to effectively build cybersecurity-specific skills, especially when technology is refreshing every year. He adds that the need is also diversifying. From cyber attack insurance agents to cyber fluent communications officers, Raduege says that the need to get the next generation of workers cyber-ready extends even beyond information technology.

“We need attorneys who know the difference between a botnet and a spearfish…but can also explain that to a judge and a jury,” he says.

However, creating a cyber-talent pipeline isn’t without its challenges. Raytheon, a defense company and top sponsor of this year’s NCCDC, and Zogby Analytics conducted a survey of Millennials on cybersecurity, and found 82 percent of young adults ages 18 to 26 had never had a high school teacher or guidance counselor suggest a cybersecurity career. Less than 25 percent are even interested in a cybersecurity job. That number drops to 14 percent for young women.

“We teach our young children right from wrong, and I think we need to do this specifically in their [digital] connectedness,” says Jeff Jacoby, a director for Raytheon intelligence, information, and services. “The term ‘cyber’ has not made it into the mainstream [careers].”

Mr. Jacoby’s solution? Advance education and awareness as early as possible.

For example, Raytheon sponsors a scholarship for elementary school teachers who innovate ways to teach STEM concepts, in addition to sponsoring numerous competitions.

“[Competitions are] really a way for colleges and universities to assess their own cyber security programs to make improvements,” he says.

These early initiatives could be paying off. For Duffey, his interest in cybersecurity started with competitions in high school and continued when he joined RIT’s Security Practices and Research Association (SPARSA), which runs its own national cybersecurity competition. The competition, he says, is key.

“When you look at other fields, like sports, [there’s a football] quarterback – it is kind of sensationalized. People look up to these people,” Duffey says. “I think something really important is having some milestones people can shoot for to get recognition.”

The 2014 competition, which took place this weekend, at least had one storybook championship moment: the underdog won. University of Central Florida, who participated in the competition for the first time last year, beat RIT for the top prize.