Is Facebook engaging in racial profiling for advertisers?

Advertisers can target 'multicultural affinity' groups on Facebook, but the social network says categorizing people by their race-related interests is different from profiling.

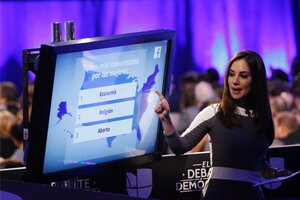

A Univision staffer shows what topics are trending from women on Facebook during a break at the Univision,-Washington Post Democratic presidential debate, Mar. 9, 2016, in Miami, Fla.

Wilfredo Lee/AP/File

Is Facebook racially profiling its users for the benefit of advertisers?

That's the accusation being leveled against the social network, thanks to a Facebook advertising feature called 'multicultural affinity targeting.' The feature analyzes user interests, likes, and group memberships to categorize Facebook users into one of four racial or ethnic groups – non-multicultural (presumably Caucasian), African American, Asian American, and Hispanic – targeted by ad sellers.

If a Facebook user likes BET or Essence, or is a member of the African American Chamber of Commerce group, for example, Facebook may identify the user as part of the African-American affinity group. Changing the site's language setting to Spanish would lump a user into the Hispanic group.

Though the feature has been available to advertisers since November 2014, it became more widely known recently when a panel discussion at South by Southwest revealed that "Straight Outta Compton," the Oscar-nominated film about Los Angeles hip hop group N.W.A., was marketed differently on Facebook depending on a user's demographic.

In fact, the film's studio, Universal, worked with Facebook to create two, very different, Internet trailers for Straight Outta Compton: one for black audiences and one for white.

Black audiences, who the movie studio assumed were familiar with N.W.A. and the film's main figures, were shown a trailer that portrayed the film as a biopic about the N.W.A. and rap as protest art, while non-black audiences were shown a very different trailer that made the film look more like a gangster movie, complete with images of group members brandishing semi-automatic weapons and clashing with police.

Facebook has come under fire for the two different trailers, which exposed its racially-targeted advertising feature and raises questions about whether the social network is engaging in racial profiling.

Facebook wants to have its cake and eat it too, writes Annalee Newitz for tech news site Ars Technica. "The company wants to offer advertisers access to multicultural communities, but it also wants to claim that it isn't identifying users by their races. So how exactly do you become part of an 'ethnic affinity' target group without being targeted as an ethnicity?"

A Facebook spokesperson responded to the claims of racial profiling by drawing a distinction between interests and identity: A member of the black affinity group may “like African-American content," the company representative told Ars Technica, "but we cannot and do not say to advertisers that they are ethnically black. Facebook does not have a way for people to self-identify by race or ethnicity on the platform.”

In other words, Facebook doesn't actually identify users by race or ethnicity – fitting with repeated statements that it doesn't use census data, names, photos, or private information to categorize users. But it does use a user's language, interests, and hometown to bundle users into "ethnic affinity groups," which it passes along to advertisers.

Of course, target marketing has been around for decades – it's why women's magazines carry ads for beauty products, children's cartoon commercials advertise toys, and the evening news is chockablock with pharmaceutical ads – so why is Facebook's ad targeting scheme so controversial?

"Even though target marketing based on ethnicity is nothing new, it has always been opt-in before," explains Ms. Newitz. "But those going on Facebook are just behaving like members of the general population. Even when a Facebook user says they like #BlackLivesMatter, they don't feel like asking to opt in to an ethnic identity – it's just one of many interests that define that person."

Facebook wants "to monetize every aspect of your identity," she writes.

And there is dangerous precedent for a feature that relies on predictors of ethnic affiliation. A 2013 study of ads displayed on Google searches found that names associated with African Americans like DeShawn or Darnell were significantly more likely to be accompanied by text suggesting that person had an arrest record, regardless of whether a criminal record existed or not.

It goes without saying that not every person with an African American-sounding name has a criminal record. Similarly, not every user who likes #BlackLivesMatter or BET is black, nor is every user who likes anime, Asian. The problem, then, according to critics, is that Facebook's claims to distinguish racial affinity from racial identity don't pass the sniff test. Social media users, not surprisingly, are raising a digital eyebrow: