Military inventions hit the civilian market

Although built for battle, these inventions are perfect in peacetime.

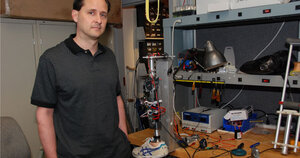

MIT researcher Hugh Herr says he had trouble finding funding for his research into prosthetic limbs before US forces invaded Iraq. Now, thanks to military grants, his innovations can help both soldiers and civilians.

Tom A. Peter

Cambridge, Mass.

Although Hugh Herr was a respected professor at Harvard Medical School, he says finding someone to bankroll a new prosthetic knee project was tough before the Iraq war. He could get funding from the prosthetic industry, but government sources showed little interest.

But a year and a half after the invasion of Iraq, the tides turned. The United States Department of Veterans Affairs provided the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and several other institutions with $7.2 million to study artificial arms and legs for amputees. The money, along with key technological innovations, has helped Dr. Herr, now an associate professor at the MIT Media Lab, create a powered ankle and knee, the next generation of prosthetics.

“If you plot prosthetic limb technology versus time, you see a major spike in innovation after every war – except Vietnam … and this current conflict is similar in that regard,” says Herr. And since his latest research has implications for other fields, such as robotics, he hopes interest and funding will continue after the Iraq war ends.

Throughout history, war has presented unique challenges that have spurred and inspired the development of new technologies – inventions that may have taken years, or even decades, to evolve in the civilian market. After more than five years, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have begun to leave their footprint on science history, generating everything from thermal imaging devices to video-game-like training platforms that are already trickling into daily life.

The military has driven technology as far back as the Roman Empire. The Roman road system, for example, was originally built for troop transport, but civilians were the ultimate beneficiaries. The same could be said about Eisenhower’s interstate highway system, designed during the cold war.

“As war became so technologically dependent, a whole range of technologies became important and many of them had civilian applications,” says Alex Roland, a history professor who focuses on the military and technology at Duke University in Durham, N.C. “Each particular conflict, if it goes on long enough, spurs its own special kinds of development.”

In America’s current conflicts, concerns about overstretching the military have allowed for significant investment in devices that allow fewer troops to do more.In years past, soldiers on guard duty watched their base’s perimeter through a pair of binoculars. Today, many rely on thermal imaging. A system created by FLIR, an imaging company in Wilsonville, Ore., can generate a clear picture of an area 20 kilometers away in total darkness and through smoke or fog.FLIR has worked with the military to provide these systems since the 1980s, seeing a boom in business during each conflict. But nothing has generated business like the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Since 2000, the value of the company’s stock has increased by at least a hundredfold.

“When you look at a situation like the last few years, where you have a couple $100 million of additional equipment being purchased [and] going into the Iraq and Afghanistan theaters, $200 million’s worth of equipment means we’re investing $20 million in additional research and development,” says Andrew Teich, president of commercial vision systems at FLIR.

Since 2006 the company has sold its thermal imaging technology to the public, making systems for boats and cars. Today, motorists can purchase select BMW models with one of FLIR’s imaging systems for an additional $2,200. Five years ago, the least expensive imaging device from FLIR cost $50,000.Prices have dropped in large part because of the volume of military orders. By introducing products to massive automobile and boat markets, FLIR hopes to keep prices low long after US troop withdrawals.

Back in Iraq, thermal imaging has been given an even longer range by attaching it to Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), another technology growing roots. Though autonomous drones have existed for at least a decade, battlefield commanders did not expect them as part of their standard toolkit until the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

Piloted by a ground operator using controls akin to an advanced video-game console, some UAVs are equipped with weapons, but most are used for surveillance.The latest generation of aerial drones fit into a backpack, and a soldier throws the plane to launch it. Desert Hawk III, Lockheed Martin Corp.’s hand-launched UAV, weighs only 6.5 pounds and measures 36 inches long. Already, Lockheed Martin sees a ripe market for pilotless planes in the civilian sector.

“You put this small, suitcase [UAV] capability in the back of a police cruiser, for example, and there’s an area where they need to have exclusive surveillance. Well, today they launch the police helicopter,” says Chuck Martello, business development lead for unmanned aircraft systems at Lockheed Martin Tactical Systems in Eagan, Minn.

Not only does a police helicopter cost millions of dollars, says Mr. Martello, but there are residual operating costs such as maintenance, fuel, and pilot training. Employing a fully equipped Desert Hawk III, on the other hand, would cost less than $500,000 and require minimal operational costs, he says. UAV makers also hope to use their systems for border patrols and crisis response, among other applications. Before UAVs enter the civilian market however, the Federal Aviation Administration must first determine safety standards.

Aside from medical and surveillance technology, the current wars are also likely to advance virtual training. Today, before troops deploy to Iraq, most visit one of three combat training centers that simulate conditions in Iraq and Afghanistan, complete with pyrotechnics and authentic locals who act as townspeople. But running a unit through such a course is time-consuming and costly (the Army spends $1.2 billion each year to operate all three training centers), so not all units are able to attend, especially National Guard units and support troops, such as truck battalions.

To fill the gap, this year the military sent the first unit through a virtual training scenario that looks like the online role-playing game Second Life. Forterra Systems, which began as a video-game company, has created a virtual Iraq where soldiers can learn how to man a checkpoint, sweep a building, and interact with locals.

Virtual training is predominantly useful for teaching soldiers certain procedures. But just like in Second Life, each online character is controlled by a real person, and, just like the Army’s training centers, locals are played by real Iraqis.

“It’s not just visually what you see, but it’s also getting familiar with and comfortable with the foreign language and the foreign customs of Iraqis,” says Chris Badger, vice president of marketing at Forterra Systems in San Mateo, Calif.

Already, the company is working with several medical research institutes to develop programs for nurses. Mr. Badger also envisions the program being used to simulate virtual disasters to train emergency service workers, or to re-create rush-hour traffic to teach new taxi drivers the lay of the land.