3-D enthusiasm is anything but flat

Like high-def television before it, 3-D technology is ahead of its content, and consumers are hungry.

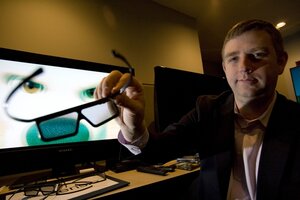

Welcome to my world: K.C. Blake is director of business development at the L.A.-based Entertainment Technology Center, where the Home 3D Experience Lab is housed.

Stephanie Diani/Special to The Christian Science Monitor

South Central Los Angeles

In a converted warehouse near one of Los Angeles’s toughest neighborhoods, a coterie of professional “techno-speculators” is playing around with what a growing number of entertainment industry folks hope the future of the small screen will be, namely 3-D.

This is the Entertainment Technology Center at the University of Southern California, where the Home 3D Experience Lab, ETC’s newest brainchild, is currently housed in a bare-bones room. The 3-D lab just opened this past week and isn’t complete yet, meaning the team is still assembling all the various iterations of 3-D as it will be experienced in consumers’ homes. But the fundamentals are in place – glasses, screens, and playback devices – says Bryan Gonzalez, the lab’s technical project specialist.

“For the state of the art in 3-D for the home environment, this is where the industry leaders can gather to discuss where it’s going,” says executive director David Wertheimer. The nonprofit research center is funded by content and technology companies, including nearly all the major film studios.

First and foremost, of course, there are the glasses. Not those flimsy, two-tone cardboard specs, but snazzy, lightweight, polarized shades or active-shutter glasses, battery-powered eyewear that whips up left and right eye content as fast as 120 times in a second. (A “auto-stereoscopic” type of 3-D content not requiring glasses is being developed, and the lab has an early version of it, but most observers say the low resolution makes it years away from viability in the home market.)

At the first setup, Mr. Gonzalez dons the passive, polarized eyewear and plunks down in front of an impressive screen.

“This is just one of many options,” points out K.C. Blake, director of business development. There are at least three different 3-D ready screens commercially available. And the Blu-ray players that the lab uses are just like those being sold at any consumer electronics outlet. Even the glasses are relatively available, both the polarized and active-shutter type.

But the one element in this “ecosystem” – as the group is fond of calling its area of study – that’s missing is the one part the folks at home really care about: the content. Right now, the team is playing a trailer from Disney’s animated film, “Bolt,” footage donated by Disney that is not available to the public.

“Similar to what happened with high-definition TV, the technology [for 3-D TV] is here before the material to watch,” points out Mr. Wertheimer.

The current momentum behind the home 3-D experience is coming not just from the movie industry but from video-game developers as well. Not unlike past flirtations with 3-D back in the 1950s and ’70s, studios are once again looking to 3-D to help prop up the theatrical release of films. And now, equally eager to get more return on the 10 to 20 percent premium spent to film in 3-D, they hope to expand the home 3-D market as a potential support for the DVD release.

At the same time, video-game enthusiasts have long pushed the evolution of consumer technologies, searching for greater verisimilitude in gameplay. The battery-powered glasses are made by a major gaming accessory developer.

As consumers get a taste of the newest 3-D technology, they are sending a clear message that they want more. Moviegoers are overwhelmingly flocking to the 3-D version over the 2-D at theater complexes. The box office for the current 3-D version of “My Bloody Valentine” has been six times that of the 2-D experience.

In an effort to groom audience demand for home 3-D content, just this week NBC ran a trio of 3-D commercials during the Super Bowl and then on Monday night, a 3-D episode of the comic spy drama, “Chuck.”

But as many audience members who watched with the older cardboard glasses noted, the foray was a bit feeble. “I don’t like watching TV with those silly glasses,” says Erica Fedderly, a 20-year-old student at Santa Monica College, who says they also strained her eyes. Both of these are familiar complaints from past industry moves into 3-D, says Christopher Sharrett, a film studies professor at Seton Hall University, in South Orange, N.J.

Wertheimer notes, “The NBC experiments with 3-D were viewed almost exclusively on existing TV sets, but it was nowhere near the movie-house experience or what’s in our lab, which represents consumer homes of tomorrow.”

The peacock network didn’t do the technology any favors by rolling out such an “old-tech” effort, says Michael Meadows, president of home entertainment for New Wave Entertainment, a production and marketing firm in Burbank, Calif. Nonetheless, 3-D is what he calls a “game-changer” for the industry. “It’s so immersive, and in the home environment, it is really a dramatic and engaging step forward in terms of storytelling.”

Burbank-based 3ality Digital systems produced the NBC commercials and the TV episode. The company has been aggressively exploring new sources of 3-D content, including live pro sports events. “It’s way past the passing-fad stage,” says CEO Steve Schklair. “It’s like high-def.... Once you see it you don’t really want to go back.” He anticipates momentum building quickly as consumers get a taste for the results.

“There aren’t really a lot of technological barriers to get through,” says Mr. Schklair. The biggest challenge from a hardware standpoint is the dizzying array of encoding, playback modes, monitor capabilities, etc. – in other words, conflicting technical protocols between manufacturers, not unlike the old VHS-Beta battle. The Society of Motion picture and Television Engineers has formed a work group to make recommendations and has met with the researchers over at ETC.

While 3-D has a ways to go for TV consumers, video-gamers are way ahead on the experience. Gonzalez suits up with his Active shutter glasses and powers up a PC connected to a 3-D-ready screen. A weird, bottom-heavy critter cavorts through meadows full of waving flowers, evading a Tyrannosaurus Rex-like creature, all in vivid 3-D, despite the fact that the game, “Spore,” was not released with 3-D encoding. But Nvidia’s software can “backwards render” existing games, meaning that gamers are already able – with a modest investment in glasses, 3-D enabled screen, and the proper video card – to have a full 3-D experience using their existing library of games.

“The gaming world is leading the way on this,” says Michael Lewis, CEO of RealD, an industry leader in 3-D technology, “if for no other reason than they already know the potential of 3-D in the home and are pushing hard for it.”

Like others in the industry, Mr. Lewis says that while 3-D TV is not currently a mainstream home consumer option, it is coming in three to five years. “It replicates the way we see,” he says. “Once people experience it – the really best version out there – it’s what they’ll want.”