Google Doodle: How Rosalind Franklin photographed DNA

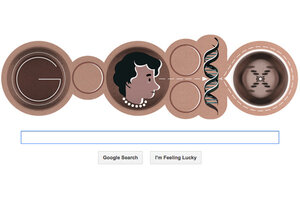

Thursday's Google Doodle celebrates the birthday of Rosalind Franklin, the first photographer of DNA.

A Google Doodle on Thursday celebrates Rosalind Franklin, who captured one of the first images of DNA.

Photographs document the stations of human life: the snapshot of a young child tossing a ball, the image of a young bride coming down the aisle, the portrait of an old man lined with age and wrinkles.

But when Rosalind Franklin took an x-ray diffraction image of DNA in 1952, the scientist had captured more than a second of humanity. She created an image of the building block of humans. This photo of DNA was referred to as Photo 51. In her lifetime, Ms. Franklin received only token recognition of her contributions to the study of DNA, while James Watson and Francis Crick were widely hailed as the scientists that discovered the molecule's double-helix structure.

Thursday’s Google Doodle celebrates what would have been Rosalind Franklin’s 93rd birthday with an image of Mr. Watson and Mr. Crick’s double helix – and Franklin’s Photo 51.

Franklin was born on July 25, 1920 in London. She exhibited a love of science from an early age and enrolled at Newnham College in 1938 to study chemistry. After she graduated with the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree (Cambridge did not award degrees to women until 1948), Franklin worked as an assistant researcher at the British Coal Utilization Research Association. In 1946, she moved to Paris to work at the State Central Chemical Laboratory Services. There, Franklin learned how to do x-ray diffraction from crystallographer Jacques Mering. X-ray diffraction allows researchers to determine the structure of a molecule, and is the technique Franklin would later use to take Photo 51 of DNA.

Five years later, Franklin began working at the biophysics unit at King’s College in London. It was here that the scientist took the first-known picture of deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA. However, Franklin did not receive credit for her discovery. In Jan. 1953, Maurice Wilkins, a fellow researcher at King’s College, gave her picture of DNA to her competitors – Watson and Crick, altering the DNA-double-helix-discovery narrative.

In March 1953, Watson and Crick published their model of DNA, and a month later, in an article in "Nature," gave a nod of acknowledgement to Franklin’s work in a footnote.

Franklin did nothing to protest this inadequate acknowledgement of her work, says Franklin’s biographer Brenda Maddox in a 2002 interview with NPR. Over 40 years after seeing Franklin’s Photo 51, Watson publicly acknowledged that seeing it was the “key event” in understanding DNA, Ms. Maddox writes in her book, “The Dark Lady of DNA.”

Around the same time that Watson and Crick’s discoveries were published, Franklin left King’s College for Brikbeck, refocusing on coal research and virology. In 1956, she was diagnosed with cancer and died on April 16, 1958 at age 37. The scientist worked up until her death.

In 1962, Crick, Watson, and Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize for their discovery of the DNA double helix structure that was also seen in Rosalind Franklin’s photograph.

It has been debated whether or not Franklin would have received the Nobel, had she lived. The Nobel Prize has only been awarded posthumously twice; the Statutes of the Nobel Foundation were changed in 1974 to state that a prize cannot be awarded posthumously, unless the death has occurred after the announcement of the prize.

Editor's note: This article has been changed from its original version to better clarify Watson and Crick's role in DNA research. They were the first to discover the molecule's double-helix structure.