Why pterosaurs were probably landlubbers

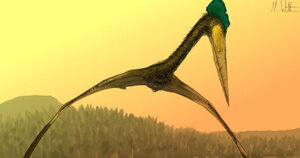

An artist’s sketch of a giant azhdarchid pterosaur. The creature has a wingspan that is over 30 feet long. Scientists say the animals spent more time above land than water.

Mark Witton

For folks who study dinosaurs, questions have long shifted from “What is it?” to “How did it interact with its environment?” For the latest example, look no further than those flying giants of yore, pterosaurs.

Apparently, many of them weren’t fish eaters who skimmed the waves like gulls or pelicans, scooping up their meals. Instead, they were more likely to be land dwellers who hunted at least as much by hoofing it as by flying. This notion comes from paleontologists Mark Witton and Darren Naish of the University of Portsmouth in Britain.

After examining a group of fossil skeletons that included some of the largest known pterosaurs (think 30-foot wingspan and a 6-foot-long skull, including beak), they determined that these prehistoric creatures were far less suited to walking in marine mud or wading in lake muck than for stepping out across terrestrial soils. The animal’s stiff neck structure and weak jaws were also far better suited to nabbing prey walking across the landscape than to enduring the sudden, forceful impact of scooping prey out of water in midflight. Among the possible munchies: large fruit or dinosaurs up to the size of a fox.

A final clue: More than half of the fossils in the group were found in what would have been terrestrial environments. (Ding! You are now free to walk about the country.)

The results appear in the current issue of the online journal Public Library of Science One.