Thanksgiving story: A 'Lost Boy' and the kindness of strangers

As bombs fell on a Sudanese village, an anonymous hand reached out of the chaos and saved 3-year-old Peter Ter. The odyssey that followed – wandering the globe along with thousands of other Sudanese 'Lost Boys' – would be as remarkable for the kindness of strangers as it would be for the boy's resilience.

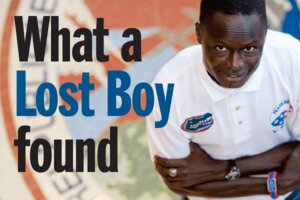

"I am talking with you today because people I didn't know helped me survive,"says Sudanese 'Lost Boy' Peter Ter, the subject of the cover story on the kindness of strangers featured in the Nov. 25 issue of The Christian Science MonitorWeekly.

Ann Hermes/The Christian Science Monitor

Jacksonville, flA.; and Waltham, Mass.

As he arrived, at last, to the names that began with "T," University of Florida President Bernie Machen paused while reading the list of 2008 graduates. There was, he told the huge crowd gathered at the O'Connell Center, a particular student he wanted to stop and honor.

This student, Dr. Machen told the 8,500-some graduates and their families, had learned to read and write by tracing letters in the dirt in a Kenyan refugee camp. He had arrived as a teenager with nothing, put himself through school, and had, against all odds, studied his way into the hearts and minds of Gator Nation.

He asked Peter Ter to rise. And as the lanky Sudanese man stood in a sea of black mortarboards, Machen turned his attention to the upper seats. "Could Peter's family also stand?" he asked. There, for all to see on the Jumbotron, stood Mr. Ter's "family": a motley collection of unrelated white Southerners – a dentist, a schoolteacher, a professor, and others – waving eagerly at the young man below.

Fourteen thousand people stood and applauded. And Ter – who just a few years earlier had never seen a movie or even a light switch, and who years before had wondered whether he would live or die in one of the world's most heartbreaking exoduses ever created by war – looked around and smiled shyly. He walked in his easy, deferential stride up to the stage. And then the "Lost Boy" – the title given to Ter and the other children from southern Sudan who wandered for years after being violently separated from their families – turned to the crowd and grinned, and extended two long arms in the Gator Chomp.

"Everyone just went crazy," recalls Daniel Schellhase, a Jacksonville dentist and one of those members of Ter's "family," who breaks into a broad, almost bewildered smile at the memory.

The scene was a perfect example of what many scholars would insist is an increasingly scientifically recognized fact about the human condition: People reach out to others, and often do so across great cultural, economic, and philosophical divides.

Ter is the first to point out that his story is only partially about him, and equally about the many friends and "family" members who have adopted him – and whom he has adopted – throughout his unlikely global odyssey, from northwest Kenya to sunny Florida to the cold mountains of Azerbaijan and back to academia in Boston.

It is a story of kindness. And it is the story, in its elemental sense, of thanksgiving.

"Being strong is a part of my nature," Ter said in one of several Monitor interviews during the past year. "Being able to learn without being held back by all of the bad things. But I am talking with you today because people I didn't know helped me survive."

Ter was tending cattle outside his village the day the planes came. This job was a common one for young boys in the agriculturally rich Unity State of what is now South Sudan; little Peter was probably about 3 years old, but he had been going to the cattle camps for most of his short life – riding on his father's shoulders, or carried by an older brother who would plop him down on the grass if it was time to wrestle or play with the other kids.

The young children stayed with the calves while the men moved their herds toward the river, or to new pastures. The women were in the village, or maybe nearby fields. Ter's family – his parents and their nine children – were not educated, but they never went hungry. This section of Sudan was a breadbasket, which was part of the reason for the brutal, complicated civil war that raged from 1983 to 2005 between the southern, Christian part of the country and the more politically powerful North, which was Muslim and less endowed with natural resources.

By the time the war came to Ter's village, Nyandong, in the county of Payinjiar, the North had already begun a bombing campaign targeting the South, dropping explosives over communities and cattle camps and killing as many people and animals as possible in an effort to crush the emerging Sudan People's Liberation Army. The children heard the rumbling of the military jets, and looked up to see the bombers swooping toward them. Through his child's eyes, Ter remembers running and chaos.

But there was kindness even among the bombs. Someone – he doesn't remember who – grabbed his hand and pulled him to safety. Ter was separated from his parents; it would be years before he discovered whether they lived or died that day. He eventually also lost track of his siblings, some of whom were taken and pressed into service as child soldiers.

But those anonymous hands, grasping to pull the young child to safety, reached out to him again and again.

"I had people who would grab me by the hand and run because they didn't want me to die," Ter says.

The built-in inclination to sacrifice for others

For centuries, social theorists have explained human behavior largely through a rather grim lens. People, according to these generations of scientists and philosophers, are inherently violent and territorial, inclined to protect their own kin, kill off competitors, and take as many riches for themselves as possible.

But in the past few years, scholars in fields ranging from psychology to sociology, economics to biology, have produced a groundswell of research bolstering an alternative perspective. Central to human existence, they have found, is a complex, snowballing mix of what researchers often call "prosociality" – a mix of empathy and gratitude, kindness and love, altruism and cooperation; all those qualities that were on display at Ter's graduation ceremony at the University of Florida arena, as well as back on that day he lost his family.

Some recent studies, for instance, have identified altruistic tendencies among primates and human babies under 3 months of age. Others show that perceived distress in others triggers caregiving behavior. "Public good" experiments, in which people must decide whether to share or keep resources, show that the initial human inclination is to give, while other new research reveals that people report more happiness when they spend on others than when they spend on themselves.

"The science of altruism has moved way beyond the old debate of does it exist or not," says psychology Prof. Dacher Keltner, who directs the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley. "Now we're thinking about all the various motivations for why people sacrifice on behalf of other people and non-kin – pretty routinely."

In other words, the experts would like to explain the remarkable story of Peter Ter.

Humbled by a benefactor's generosity

With a growing group of children also separated from their families, eventually numbering into the thousands, Ter walked for months toward a refugee camp in Ethiopia. Then, when those camps were attacked, they trekked 1,000 miles back through Sudan toward Kenya. He remembers gunfire and bodies.

The horrors of the 20,000-some Lost Boys of Sudan – and a large number of Lost Girls – has been well documented. Throughout their migrations, the children hid in the bush, became the prey of lions and soldiers and starvation, walked until their feet bled, and passed through a nightmare of shelled villages and corpses. Thousands died, according to the United Nations.

Ter, for his part, is matter-of-fact, but shies away from discussing details of the ordeal. The memories still wake him up at night, he admits. But then, he says with a smile, he just gets up and turns on National Public Radio. It soothes him.

"I love NPR," he says. " 'All Things Considered' – that is my favorite phrase."

This buoyant attitude today is a hint of what helped him survive his childhood in the UN's sprawling, barren Kakuma Refugee Camp in northwest Kenya.

When the survivors arrived, they were called the "minors." Overwhelmed aid workers tried to quickly arrange basic schooling, as well as one meal a day. But the children were generally left to fend for themselves.

Ter promised himself he would become literate. He taught himself English by reading the Bible. He learned to write by tracing English letters in the dirt.

Crime and disease were rampant in the camp. But there was also generosity. A young man about a decade older than Ter, named James Thak Dhiel, came from the same county in Unity State and took a particular interest in the skinny younger boy who was so often studying. Mr. Dhiel knew that Ter left for school in the morning without eating, and came home in the evening dizzy with hunger, so he regularly slipped the boy a shilling or two to buy extra food. He soon took a big brother role in Ter's life, Ter recalls, inviting the younger boy to stay in his compound of thatched-roof homes built with materials provided by the UN. He kept an eye out for the bandits and corrupt soldiers who regularly preyed on the younger camp residents. "I will always be so humbled thinking of him," says Ter, who has lost touch with Dhiel but knows the man was relocated to Australia in 2002. "There is always humanity. Everywhere people will give, regardless of whether they have anything."

People are also quite adept at quickly identifying who is likely to be trustworthy and "prosocial" in their own right, and are more likely to help those perceived to be empathetic and altruistic themselves, according to recent studies. Perhaps this is why Dhiel reached out to Ter. Or perhaps he simply saw a child struggling, one that maybe reminded him of relatives from home who were long gone, or by this point trapped as child soldiers. Ter says he never asked Dhiel about what happened to his family. In the camps, there are some subjects too painful to discuss.

Almost nine years after he had arrived at Kakuma, Ter was given refugee status by the US government. When that day came to say farewell to Ter, who would soon be flying across the ocean to a place called Florida, Dhiel took him to a market and had him fitted for a new outfit. Dhiel also offered the younger boy a special present: a pair of orange and blue shorts, discovered at one of the used-clothing stands that dotted the camp, emblazoned with the word "Florida," along with a picture of what Peter identified as a crocodile.

"I was a Gator when I was still in Kenya," Ter says with a grin.

'You don't look like you're from around here!'

Adam Lohse remembers the phone call during the fall of 2001 from his friend Meg Young. She had run into these Sudanese guys at the grocery store, she said, and she was going to have a party for them. She wanted Mr. Lohse to be there – after all, he was a fellow churchgoer, interested in missionary work, and here were people around their own age, in their own backyard, who certainly needed a welcome.

That was just like Ms. Young, Lohse had thought with a smile, to just go up to a bunch of people at the Publix supermarket and say "Hey, you don't look like you're from around here!" But he was pleased. Jacksonville was a growing destination for refugees from around the world; it was God's work to reach out to these people.

In a 2003 University of Chicago report titled "Altruism in Contemporary America," University of Chicago researcher Tom Smith analyzed survey data for trends about empathy and altruistic behavior and constructed scales that measured the various levels of this prosocial behavior for different demographics. Although nonreligious people were regularly altruistic, overall data showed that those who consider themselves religious – particularly those who engage in practices that identify them as devoutly religious – were more likely to engage in altruistic behavior.

Perhaps, then, it was Christianity that connected Lohse with Ter. But whatever the forces at work, it was a time when Ter needed a friend.

He had arrived in Jacksonville a few months earlier, in August of 2001. The trip had been traumatic – he had left his friends in Kakuma and flown to Nairobi, Kenya's capital, and then on to New York, and from there to Florida. None of the Lost Boys had been on a plane before, and many were airsick. Ter recalls feeling disoriented and depressed, and he kept his head in his hands.

In Jacksonville, a representative of Lutheran Social Services, the organization contracted to process refugees landing in Jacksonville, escorted him and another Lost Boy to a ground-floor apartment overlooking a parking lot on the south side of town. They didn't know how to use the lights; running water was new to them. Ter remembers sitting there in silence. He and his roommate had known each other for years, he recalls, but they acted as if they were perfect strangers. They were in shock.

They stayed inside for a number of days. But soon, Ter says, he realized that he needed to just get out and walk around. There would be no way to integrate into this new society from his apartment building, he knew. And integration was crucial: He needed to get a job.

Although he could speak, read, and write English, this was daunting.

According to official documents, Ter was 21 years old – far too old for high school or to be placed with a host family; the age at which the US government expected him to quickly move off federal assistance. He would have free rent for three months, and then he was on his own.

That age, however, was arbitrary. Few of the Lost Boys knew their actual birth dates, so officials gave them approximate ages based on height. Ter is tall, so the US government decided he was born in 1980. When, years later, he connected over the phone with a brother in Sudan who had also survived, Peter learned he was five years younger.

The American woman at the grocery store had been friendly, so Ter was happy to take her up on her invitation. And he eagerly accepted when Lohse, whom he met at the gathering, invited him out for ice cream.

"We thought this would be a great way to introduce him to something of the US," Lohse recalls. "He took one bite and said, 'Ugh, too sweet!' "

They kept talking, though, and when Lohse asked Ter what he really needed, Ter said that he would like a GED study guide. He had already realized that to get ahead in his new country, he needed education. So they went to the Barnes & Noble in the pretty Mandarin section of Jacksonville. Ter, a book lover, was amazed. It would become one of his favorite spots in the city.

Lohse also called his friend and fellow churchgoer, Mark Biery. Mr. Biery runs a warehouse that packages and distributes shredded Mylar, that shiny metallic stuff that is used to fill gift baskets. He has been hiring refugees since the 1980s.

"They would do repetitious work," Biery says. "I'd show them how to do it. It was a place for them to get a minimum wage and get started, and then after six months to a year I'd encourage them on to other jobs. I'd say, 'You don't want to work here. You can do better than this.' "

Biery agreed to give Ter an interview. Quickly, the young man from Sudan with the wide smile became one of his favorite employees.

"Peter was thankful to God to be alive," Biery recalls. "He found thankfulness in everything he did."

For his part, Ter loved the job. He drove a forklift, moving large packages from one location to another.

"I learned how to drive a forklift before I could drive a car," he recalls gleefully. "It was amazing. I'd drive through the aisles ... it was like dancing."

Meanwhile, he and Lohse, who was in seminary at the time, became closer friends. Lohse taught him how to play American football, and brought Ter books on history, which Ter loved. He invited Ter to Thanksgiving dinner at his mom's house. Meanwhile, Ter tried to teach Lohse a few words of his Nuer language and culture. When Lohse proposed to his longtime girlfriend, Ter was one of the first people he told.

At some point, Lohse says, it was clear the relationship was no longer about one man helping the other.

Ter would accompany Lohse to church, but told him pleasantly that he had no intention of converting or joining. Ter was a Roman Catholic, like his parents, and although he says he loves church, he also says his spirituality and faith is grounded in humanity rather than in any god.

So the two men agreed to disagree on the specifics of the heavens. And, on earth, it was a real friendship, with kindness, love, and support flowing both ways.

Uncanny ability to fit in

Sandy Fane was teaching a citizenship class at Jacksonville's Samuel W. Wolfson High School when a tall, polite young man stopped her in the hallway in April of 2002 and asked if she might help him find his GED class.

Ms. Fane, a vivaciously friendly woman who had already retired from teaching, was struck by the man's bearing.

"He was very quiet, very soft-spoken, but his posture was gorgeous," she recalls. He had a presence; a confidence and deference all wrapped together. She talked with him for a few minutes and found out his name, Peter, and his background, Sudanese.

Fane and her husband, Gary, had recently returned home from a vacation in Tanzania and Kenya, and had just seen a documentary about the Lost Boys. Something moved her to offer Ter her help.

"I'm a mother. I said, 'If you ever need anything, if you have even a simple question, give me a call.' " She gave him her phone number. She also dropped a spare computer off for him at the Lutheran refugee services office.

Lynn Underwood, a scientist who has written extensively about altruism, says that reaching out to a stranger is one of the hallmarks of compassionate love, a move that taps into something deeper in humanity that connects us.

"When we help a stranger it sets up the question: Why would we do something for someone from whom we're not expecting something in return? For me, it happens because it creates something unique and beautiful in the world."

The Fanes invited Ter and the Sudanese roommates with whom he was living at the time over to their home, a geodesic dome tucked into a leafy, moss-draped cul-de-sac.

"It's just like the houses at home!" she remembers the men laughing, while they sat on the back porch, describing the construction of Sudanese huts made of mud brick and thatch.

Gary Fane, an accounting professor, was also impressed by Ter. He offered to help the younger man study for the GED tests, and later helped connect him with the local junior college. The more time they spent together, the closer they became. He saw something of himself in the hardworking Ter – Mr. Fane had worked his own way through college and graduate school, earning his master of business administration at night while saving pennies and putting his faith in education. Eventually, he took a fatherly role in Ter's life.

"He's like just another one of our kids," Mr. Fane says. "Our kids were all grown. He's the fourth."

He helped with the younger man's taxes, and got the phone calls when Ter had car trouble. Later, when Ter went off to the University of Florida, leaving his Jacksonville apartment behind, the Fanes suggested Ter consider their house his home. When Ter returned on break, he had a bedroom, as well as a ready spot on the couch to watch football with Mr. Fane.

Too much football, Mrs. Fane says.

"Peter, he didn't know about American women. I said, 'No more football. It's driving me crazy.' "

She put a sign on Ter's bedroom door: "When the boss is happy, everyone is happy."

He laughed, and from then on called her "Mama Boss."

By that point, Ter's friends had multiplied.

The Fanes had helped connect him with a job at a natural food store, which had better hours for school than the warehouse work (and also turned Ter into an organic-foods devotee). There, a friend said she would pay for him to get the gaps between his teeth fixed by Dr. Schellhase, the dentist. But Schellhase, who had supported other low-income youths, agreed to do the work pro bono. Ter wrote him a moving thank-you note. And from then on, the two became friends.

"We could be having the worst day, with everyone grumpy, and when Peter came into the office, everyone was happy," Schellhase recalls. "He is just a delightful person."

Ter seemed to fit in everywhere and anywhere, his friends say, with a stunning ability to ingratiate himself with the least likely of supporters, from old-school racists to star University of Florida basketball players. (His friends laugh at the memory of Ter telling them, matter-of-factly, that he had met some guy named Noah, who had offered him tickets to a University of Florida basketball game. He was talking about campus celebrity Joakim Noah, who now plays for the Chicago Bulls. When Mr. Noah invited Ter to party with the team after a game, Ter politely declined, saying he had to study.)

When Ter was accepted in 2004 to the University of Florida, Schellhase paid for his room and board. And when Ter, a political science major, wanted to travel to Israel for a summer course, the dentist was eager to help – even if he was, as he describes it, "a nervous wreck."

"I mean, Peter doesn't exactly blend in," he says with a laugh. "But the first picture I get? Peter with his arm around a guy with a machine gun."

That first picture was with Israeli soldiers. The next was with Palestinians.

"That's so Peter," Schellhase says.

Ter laughs at the memory. The border crossing had been tense, he says. The Israelis were wary about a Sudanese man entering their country, despite his American passport. (Many Sudanese have attempted to flee into Israel.) So Peter, acting friendly, asked if he could take his picture with them. They were curt at first, but he persisted with what Biery, his former employer, describes as a "God-given gift with people."

Ter was polite; he joked, he listened. He radiated respect as well as humble, but solid, self-confidence. After all, one of his friends explained, there was nothing left for Peter to fear.

One of the soldiers, a woman carrying an automatic rifle, sharply rebuffed his request for a photo, saying that her husband would kill her if she had her picture taken with a strange man.

"Kill you?" Ter asked. "But you're the one with the gun!"

Everyone laughed. They took the pictures and waved the car through.

Paying it forward

The thing about kindness is that it often comes full circle. In popular culture this has become known as "paying it forward"; in science and scientific surveys it is a clear factor in people's propensity to engage in altruistic behaviors of their own.

With graduation looming, Ter thought he might want to go into the military. He wanted to give back to the country that, as he puts it, restored his dignity. He mentioned this idea to one of his favorite professors, Dennis Jett, a former US ambassador to Peru and Mozambique.

Ambassador Jett suggested another idea: Peace Corps.

Ter was assigned to teach English in remote Azerbaijan.

"I'm sure out in the sticks in Azerbaijan they haven't seen an African before," Jett says. "But this is a kid who at a very, very young age, not just got put out on his own, but made his way in refugee camps, then adapted to the United States. I thought he had the kind of adaptability to get through it. He's just a sweet kid and such a fine young man; it's hard not to like him."

Ter jumped fully into the job. He learned Azerbaijani, at that point his third language, and he decided he would not leave his host town while he was in the Peace Corps. He extended his two-year stay to three years. And he regularly defended the United States to skeptics, according to him and others familiar with his time there.

"I would tell people, 'Look, I was not born in America. I was born into war, poverty, disease. America adopted me. America restored my dignity. How can you think of America as a bad society?'"

He was convincing enough that he caught the attention of the Azerbaijani security forces, whose offices Ter walked by on his way to work. It was a small town, Ter says, so everyone knew that he was there. They taunted him, Ter recalls. In his way – unfailingly polite but also firm – he pushed back.

"They would shout at me, 'Why is America killing Muslims?' I'd say, 'That is not a good question.' " He suggested that there were plenty of things about which he could criticize the Azerbaijani government; they could agree to treat each other's homelands with respect.

As Ter describes it, he and the security officials started off on two sides of a fence – Ter walking to school, them in their compound. Eventually they started debating at the fence. Then one day, as they argued, the security officials asked Ter in for tea. They became friends – across layers of cultures, attitudes, and languages.

It was yet another thanksgiving.

In 2004, Ter discovered through Sudanese connections that his parents and siblings had also survived the war. He spoke with his father, who had walked 400 miles to find a telephone just to call his son.

One day, Ter says, he might return to Sudan to see his biological family. But at the moment his life is here, and he wants to live in the present and future, not the past. Ter today is a graduate student at The Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., where he is working toward a dual master's degree in sustainable international development and in coexistence and conflict resolution.

He says he hopes to continue giving back to the US, perhaps through work in the State Department.

He is scheduled to move to Turkey in May, as part of a State Department-sponsored study program.

There, he hopes, the map of kindness will continue to grow.