The fight against fake news is putting librarians on the front line – and they say they’re ready

As fake news and complex immigration orders have inundated the public sphere, libraries are opening their doors and fact-checking skills to people of all backgrounds seeking information.

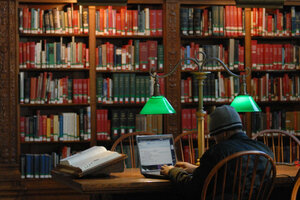

People work on computers and use internet access in the reading room at the Boston Public Library.

Mary Knox Merrill/The Christian Science Monitor/File

In the fight against fake news and divisive, exclusionary policies and views, a not-so-new resistance is brewing among the nation’s librarians.

The first few weeks of President Trump’s administration have shown that resistance can come in unexpected forms. From little girls and elderly women in bright pink cat hats taking to the streets to National Parks rangers writing a firestorm of climate change facts on Twitter, Americans have stood up at rates not seen in recent years to protest the new administration’s stance on such issues as climate change, immigration, refugees, gay and transgender rights, women’s rights, and religious freedom.

Now, librarians are joining in a resistance of their own. Some have created websites to provide information for refugees and undocumented immigrants while others built book displays that focus on Muslim culture or the LGBT community, and many have shared ideas by joining together on social media. Boasting legal documentation and subscriptions to reputable publications and archives has also given the libraries a leg up in providing communities with accurate information as fake news stories run rampant on social media.

While some have questioned the movement and its ability to politicize neutral, government-funded library environments, librarians say advocating for free, open spaces for all, as well as providing legal resources and accurate facts, shouldn’t constitute a political statement. For them, taking a subtle stance against the administration simply involves showing up and doing their jobs.

And in turn, many have become hopeful that some of the patrons who left their local library behind as the proliferation of smartphones put answers in the palms of their hands will see a renewed value in visiting their local library.

“This is like waving a red flag in front of bull or throwing red meat into a tiger’s den for librarians,” Christian Zabriskie, the executive director of Urban Librarians United, an advocacy organization that promotes libraries in large cities, says of fake news and legal questions raised by Mr. Trump’s immigration order. “That’s the war we’ve been getting ready for for a long, long time. We’re not really doing anything different than what we’ve done before, we’re just being called on to do it differently.”

Trump and fake news are far from the first cause to spur them to action. Librarians have often responded to the current climate when privacy, free speech, or access to information becomes compromised.

Following 9/11 and the passage of the Patriot Act, which included a provision that allowed investigators to retrieve an individual’s library records with a warrant, many libraries stopped keeping browsing and checkout records, and they’ve since become safe places to use the internet or check out books and information without leaving a paper trail.

They also host free tax preparation and resources fairs, serve as gathering spaces for politically charged or educational events and speeches, and promote works that highlight the diversity in America. Some have joined in efforts to archive public environmental data, following fears that the Trump administration may erase the kind of environmental evidence used to back regulations and bring crises, such as the water problems in Flint, Mich., to light.

From curating book collections to creating welcoming atmospheres, some argue, some say it’s impossible for libraries to remain completely above the political fray.

Rebecca McCorkindale, the assistant library director and creative director at the Gretna, Neb., library, echoed that sentiment. Earlier this month, she designed a graphic that reads “Libraries are for everyone” and is adorned with cartoon people of diverse races, religions, and ages. She made these available for free downloads, hoping other librarians would print and display them as markers for the safe spaces the institutions can become.

Since then, Ms. McCorkindale says thousands of people have visited her blog daily, and many have submitted translated versions of the graphic.

“Libraries are my life, so when I get home I don’t stop doing stuff,” she said of creating and promoting the design in her free time. “I still think this should not be a political statement, that everyone’s welcome. It’s kind of heartbreaking that by indicating that everyone is welcome, people now feel threatened by that.”

Others have adopted inclusive and education themes, hoping to expand their reach into the community.

In Charleston County, S.C., a display titled “Y’all Means All” that showcases LGBT young adult selections has stood in the young adult section since last June. While it began as a celebration of pride month, the display has become a permanent fixture, following the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando that targeted a gay club and increased incidents of bullying or exclusionary behavior.

Andria Amaral, the library’s young adult services manager who built the display, says that creating an inclusive environment for young adults has been a key part of her job. While many children and teens are introduced to the library by their parents, the branch also makes a point of reaching out to vulnerable youth, showcasing resources that celebrate diversity.

“The things that we stand up for as librarians are intellectual freedom, and good, verified sources of information,” Ms. Amaral says. “This is our bread and butter. If that’s being challenged and that makes us political, then so be it.”

A library likely wouldn't have prominently showcased LGBT teen literature some 20 years ago. But as society has shifted, libraries have as well, taking on new tactics to boost their inclusive natures.

“Librarians are a pretty passionate group,” she adds. “A lot of people still have old fashioned ideas of what public libraries are. And we are so much more than that now.”

But others have argued that libraries and librarians should limit how political they become, and noted that going too far could put librarians at odds with the law. The Hatch Act, a measure that limits the political actions of federal employees in the scope of their jobs, as well as various state measures, place restrictions on how tax-payer money can be used for politics.

"I can’t see any reason to embrace a political librarianship," Lane Wilkinson, the director of library instruction at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, wrote in a 2011 blog post. "Either ‘political’ is interpreted to mean 'fair, honest, offering multiple viewpoints, etc.', in which case that’s no different from what we’ve always been obligated to do. Or, ‘political’ is interpreted in a stronger sense, meaning 'a duty to actively engage in political activities' in which case we’ll need to make a librarian exception to the various laws following the Hatch Act, and we’ll need to explain how that duty is peculiar to librarianship and not founded in the more properly basic citizenship."

While the role of librarians in the Trump administration might see continued debate, some are hopeful that shedding new light on libraries and what they have to offer could benefit the institutions. A public rebranding of libraries could draw more cardholders, bringing people back to the institutions who have left in favor of finding answers on the internet — especially those who are seeking vital information free from tainted fake news.

“You hear the refrain over and over again that libraries are going to become obsolete,” McCorkindale says. “And if all we were was book warehouses we would probably would go the way of Borders. A lot of people have not realized that we are information specialists. It’s funny how little people know what their library can do for them. I know at my library we can just go on and on about what we can do for a community – and what we’ve done and what we hope to do. ”

Acting in ways that appear to push back against the government could have its risks, Mr. Zabriskie, who also works as an administrator for the Yonkers Public Library in New York, says. While he has some concerns come budget time, he notes that libraries and their workers still receive respect from liberals and conservatives alike, and stripping funding from the popular resource could spell trouble for legislators and other officials.

He does hope that more people will see their libraries through a new lens, disregarding stereotypes that center around aging books and librarians and instead understanding the role the institutions can play in the 21st century.

“We’re seeing a lot more people doing protests and going to rallies and that being just a much bigger part of people’s lives,” Zabriskie, says. “I hope that as an extension of that, people will think, I’m going to go out and learn more about this. I really hope that their first choice would be to come to the library to do that.”