‘Peanuts,’ Charles Schulz, and the state that started it all

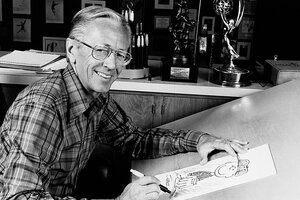

“Peanuts” creator Charles Schulz works on a drawing in 1978. A new exhibit at the Minnesota History Center in St. Paul highlights the state’s influence on Mr. Schulz's work.

AP

Minneapolis

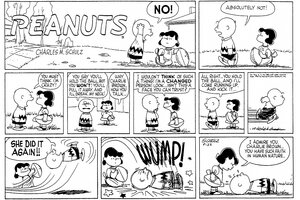

“Come on, Charlie Brown. I’ll hold the ball and you kick it.”

Readers might be surprised that “Peanuts” creator Charles Schulz was among those hoping that – maybe, just maybe – Lucy van Pelt would finally let Charlie Brown kick the football.

Although the “Peanuts” cast are thought to be different facets of Mr. Schulz’s personality, he said that they had a life of their own.

Why We Wrote This

What more is there to learn about Charlie Brown’s football and Woodstock’s birdbath? An exhibit about cartoonist Charles Schulz offers a unique window into his inspiration: the Midwest.

“He often spoke about the characters as leading independent lives,” says Chip Kidd, a New York-based graphic designer who published two books on Mr. Schulz’s work. “In one interview he said, ‘I wish Lucy would let Charlie Brown kick the football.’ I don’t think he was trying to be sarcastic. In his mind, the characters did take over.”

Just as Charlie Brown had to learn to pick himself up from failure, so too did Mr. Schulz as a shy, small kid growing up in St. Paul, Minnesota. Mr. Schulz credits his high school art teacher, Minnette Paro, for spotting his talent early on and encouraging him to follow his own voice.

A black-and-white photo of Ms. Paro from 1940 sits in a glass case at the Minnesota History Center, one of more than 150 letters, photos, and memorabilia on view as part of a yearlong exhibit, “The Life and Art of Charles M. Schulz” in St. Paul.

While fans of the iconic comic strip will appreciate the more familiar elements on display – a Snoopy-inspired Pez dispenser, a 1980s-era lunchbox – it is the exhibit’s ode to the Midwest that offers a unique window into Mr. Schulz’s inspiration.

Though he later moved to California, Mr. Schulz spent his formative years in Minnesota, which provided a backdrop for what would become well-known storylines: autumn leaves piling up during football games, Woodstock ice-skating on a frozen birdbath, or the cast of characters racing across a hockey rink.

Those Minnesota moments set the stage for an artist whose enduring creations contributed to American pop culture and offered poignant life lessons for generations: how to make lemonade out of lemons, and that perseverance wins out.

“The world that Schulz built had kids talking like adults about big things: life, death, and God,” says Mark Fearing, an author and illustrator in Portland, Oregon, whose family grew up alongside Mr. Schulz in the St. Paul area. “But there were also things that felt like part of my landscape: homes, a dog, kids going to school on a school bus. ‘Peanuts’ was radically different. ... It was a revolution.”

Midwestern influence

Mr. Schulz was born in Minneapolis in 1922 and began publishing cartoons regularly in 1947 with his weekly series of one-panel jokes, “Li’l Folks,” in the St. Paul Pioneer Press. It was here that Mr. Schulz created the name Charlie Brown as well as a dog that resembled Snoopy. After “Li’l Folks” was dropped in 1950, Mr. Schulz developed a four-panel comic strip for syndication, and “Peanuts” was born.

Over the next 50 years, Mr. Schulz would produce 17,897 “Peanuts” strips. He proudly maintained full editorial control over the cartoon, sitting down every morning with a yellow legal pad and coming up with the lettering, storyline, imagery, and colors – something rare at the time that, some say, alluded to his upbringing.

“There is the stereotype of the Midwest work ethic, and it was all over his strip,” says Annie Johnson, museum manager at the Minnesota Historical Society, an educational nonprofit that oversees more than two dozen historic sites and museums, including the Minnesota History Center. “I think people from here will also recognize repeating [Midwestern] themes of self-deprecating humor and modesty.”

Mr. Schulz took a piece of Minnesota with him when he moved his family to California in 1958, building a new ice hockey rink in a neighborhood of Santa Rosa, which opened to the public in 1969. In 2002, Santa Rosa opened the Charles M. Schulz Museum to celebrate the artist, which provided the wall panels for the Minnesota exhibit.

The panels describe all of the major “Peanuts” characters, from fan favorite Snoopy to boundary-breaking characters like Franklin – the strip’s first person of color, who appeared in 1968 – and Peppermint Patty, who in the 1960s wore shorts instead of dresses and chose sports over school any day.

“A piece of ourselves in each character”

The lessons that “Peanuts” characters taught readers through humor and metaphor – often involving unrequited love, sports, and friendship – were what made them so beloved. It’s also given the comic an enduring popularity even as print newspapers fade.

“Comic strips were a unifying, recognizable expression found in newspapers that blanketed the whole country. They had a huge impact,” says Mr. Fearing. “There’s nothing comparable now.”

Still, the St. Paul exhibit hopes to inspire a new generation of “Peanuts” fans, some of whom may have only seen the still-popular “A Charlie Brown Christmas” animated TV special. Since the exhibit opened in July, summer camps-ful of schoolchildren have visited, as have many grandparents with their grandchildren.

“Kids today might not get it as much as we do. They didn’t grow up with these memories,” says Annette Gilles, who visited the exhibit with her husband, Don, and 9-year-old grandson in early August. “But [‘Peanuts’] taught us things. We felt like we had a piece of ourselves in each character.”

For Minnesotans, those feelings are especially strong. Curators worked with their own collection of “Peanuts” memorabilia to give the exhibit a nostalgic, local touch: There are the life-size statues from the city art project Peanuts on Parade, as well as objects from Camp Snoopy, a 7-acre amusement park that was installed in the nearby Mall of America for over a decade.

What local visitors have especially appreciated, say museum spokespersons, is knowing more about the man behind the magic. A blown-up wall map pinpoints more than a dozen of Mr. Schulz’s old haunts – his local barber shop, former schools, and family home. Ms. Johnson says longtime Twin Cities residents “can spend half an hour in front of it.”

But the Midwestern elements of the exhibit are intended to welcome – not exclude – visitors into Mr. Schulz’s universe and to add new richness to an already abundant following. At the end of July, the Peanuts Collectors Club held its 17th annual Beaglefest during the exhibit’s opening weekend in order to discover some previously unseen memorabilia.

Even if comic strips may be moving toward a thing of the past, Mr. Schulz’s cast of flawed but lovable characters continues to resonate with people in Minnesota and beyond.

“‘Peanuts’ was so real and touched everyday life,” says visitor Carol Faust, of the nearby suburb New Brighton. “There was a sense of friendly competition but without animosity. Even if Lucy was mean sometimes to Charlie Brown, all the characters accepted each other as they were. There was no hate. It’s refreshing.”