Kenya's rising culture club

After social upheaval, clubs and small publishers have sprung up in the East African nation as new outlets for literary expression.

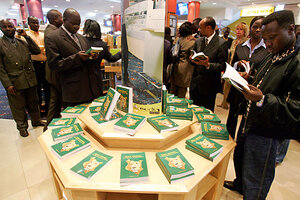

Kenyans gather at a Nairobi bookstore to read a book on the nation's politics. Clubs and small publisher's have sprung up in the East African nation as new outlets for literary expression.

Antony Njuguna / Reuters

Nairobi, Kenya

It might be just another club night in party-hearty Nairobi. In a little, second-floor downtown bar bathed in red lights and decorated with funky paintings, crunk music thumps from a high-quality sound system. Couples at tables sip drinks.

But then, after a few measures, the music stops, and a poet takes the stage. Wearing dreadlocks and an orange scarf tied around his head, Kennet B begins a spoken-word tirade against environmental degradation and corruption.

“Something revolutionary is going to happen tonight,” he announces. The crowd shouts its approval.

It’s the first Tuesday of the month, which means that the Kwani? Trust (the question mark is part of its name), a Kenyan literary collective and nonprofit publishing house, has sponsored open mic night at Clubb Sound. The event brings together Nairobi’s intelligentsia and literary dabblers.

This is ground zero for a revival of East African literature in which Kwani? is playing a leading role. Since 2003, Kwani? has published short-story collections, photography, and political cartoons. The group has also sold 15,000 copies of its yearly journal – not a huge figure by American standards, but remarkable for a market in Africa, which is not known for its book buyers. “For this space, that’s incredible,” said Billy Kahora, the editor of Kwani? “I mean, a good monthly magazine sells 5,000 copies.”

Another publishing house called Storymoja (“one story”), which sponsors similar events, has sprung up, and the Kenyan literary scene is creating buzz.

Kenyans have long been writing and, of course, telling stories. What’s new is the relative strength of the interest in domestic books.

“They’re bestsellers,” says book salesman Protus Ikutwa of the Kwani? books that occupy a few shelves at Prestige bookstore in downtown Nairobi, next to volumes about Nelson Mandela and Barack Obama. Mr. Ikutwa says the store was selling five copies a day.

Still, in a country where the gross domestic product per capita is $1,600 – about 1/30th of the United States – many Kenyans don’t have the disposable income to spend on the $10 journals. So Kwani? has begun selling individual short stories in pocket-sized booklets, not only in bookstores but also in supermarkets, for about $2.50. The goal is to harness the lower-spending end of the market, as well as first-time readers.

It’s a strategy that seems to be working. “Today, Kenyans have begun to read,” Ikutwa says. “They want to know about their country.”

Ironically, the explosion of creativity seems to be riding on the same forces that have thrown the country into the worst instability in decades, following disputed elections at the end of 2007. Kenyan society is in some kind of convulsion, and people have things to say about it.

On the one hand, there are thousands of internally displaced persons, along with widespread mistrust among Kenyans and growing insecurity – kidnappings and armed robberies are commonplace. On the cultural scene, however, the crisis has broken open a vibrant creative space – and revealed a thirst for expression, as Kenyans grapple with their country’s future.

“There’s positive chaos and negative chaos,” says Mr. Kahora in his Nairobi office. The 30-something editor smiles a little ruefully.

On his desk lie two books that rose from the ashes of the burning, looting, rape, and slaughter that gripped Kenya for weeks after the elections and killed 1,500 people. “Kenya Burning” is a glossy volume of photos, some of them shockingly gruesome, from that time. The fifth edition of Kwani?, the yearly journal whose success begat the publishing house, contains works of fiction, reportage, cartoons, and photography that deal with, among other things, the bloodshed and its social and political context.

Kahora depicts Kwani? as a youth-driven challenge to the grip of a staid African canon that has diminishing relevance for Kenya’s youth. That spirit is captured in the publishing house’s name – “kwani?” means, approximately, “so?” in Swahili.

Back in 2002, Kahora says, the generation of Kenyan writers that started Kwani? as an informal culture club – led by Caine Prize winner Binyavanga Wainaina – did so out of a sense of necessity. Many had returned to the country after sojourns elsewhere during the repressive 24-year reign of strongman Daniel Arap Moi.

“These are people who have grown up reading people like Ngugi wa Thiong’o,” Kahora says, referring to one of Kenya’s most famous authors, who published much of his writing in the 1960s and ’70s. “And they’re thinking, Man, it’s all very well to read about Mau Mau” – the anticolonial insurgents the British called terrorists – “to read about neocolonialism, to read about Marxism. But the Kenya today is all about overpopulation, it’s about HIV/AIDS, it’s about crime and insecurity. I want to read that stuff, you know? I want to see my present.”

The need to be relevant has strongly shaped the stories and media that have come out of the movement. Kwani? has made a conscious effort to give its books more mass appeal and reach a broader audience. That’s one big reason for the open mic nights. And while the books are mostly in English, many passages are peppered with sheng, the Swahili-English patois that is common in Nairobi. The covers of the more recent journals are comic-bookish, using motifs borrowed from pop culture and consumer products; pull quotes appear in choppy, faded typefaces. Kahora calls the aesthetic “funky.”

The subject matter is dead serious, though, even if the tone of the writing is sometimes irreverent. The most recent issues contain essays and interviews written by writers that Kwani? commissioned to scour the country in the wake of the election violence. Next to the essays, there are poems and reprints of desperate texts sent by people trapped in the fighting. Similarly to reports from organizations like Human Rights Watch, the books bear witness to bloodshed.

But they also add a comprehensibility and immediacy to the Kenyan turmoil, which can simply look like inhuman madness in other media, both domestic and international.

“The official reports are still written in a language that really doesn’t get to the heart of what’s happening,” Kahora says. “But if you go to the streets and talk to people – how do you capture that voice? How do you get to that place? It’s not only about violence. It’s about unemployment. Crime and insecurity are [also] related to that kind of violence.”

Kenya, in fact, is just one of the nodes of a youth-powered African literary revival. There are, for example, Cassava Republic, Farafina Trust, and affiliated Kachifo Limited in Nigeria. Perhaps the most well-known book coming out of this generation is “Half of a Yellow Sun,” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. (Kwani? distributes the book in Kenya.)

Kahora sees it as the silver lining of a new African era of weaker states and instability.

“I think Kwani? is a symptom of a renaissance,” he says, “because there are a lot of things taking place. A lot of political freedoms are coming through. A new generation is coming of age.”