A book that brought God closer

As The King James translation of the Bible marks its 400th anniversary, its deep influence and prominence are slipping.

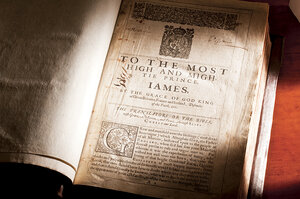

One of the original King James Bibles, printed in 1611. The King James Version, considered the ‘flagship’ by many, holds an enduring appeal – but it now faces hundreds of competing

translations.

Courtesy of Mark Thayer/The Mary Baker Eddy Library

Let us now praise a famous book – perhaps the most influential ever written in the English language. But here's the root of the matter: There's a fly in the ointment. To everything there is a season, and for some today the sway of this once mighty orator has shrunk to something akin to a still, small voice.

The King James Version (KJV) of the Bible celebrates 400 years in print this year. Its impact is pervasive and almost impossible to fully calculate. The KJV, also often called the "authorized version," has embedded itself into the very "DNA of the English language," as one writer describes it. At least 257 common phrases (the previous paragraph is stuffed with five of them) in use today come from it, one scholar has calculated.

The effect of the KJV on the way people write – and think – can be seen in works from the speeches of Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr. to the spare prose of Ernest Hemingway to Milton's "Paradise Lost" to the text of Handel's oratorio "Messiah" to the style Herman Melville employed in "Moby Dick."

Melville's novel "is more than just this story of some people sailing and a whale. It's a grand, almost religious, allegory because it's written in a language that's scriptural, which is [the King James Bible]," says the Rev. Ephraim Radner, professor of historical theology at Wycliffe College in Toronto.

Over the years, ovations for the KJV have piled up. "To read it is to feel simultaneously at home, a citizen of the world, and a traveller through eternity," former British poet laureate Sir Andrew Motion enthused. Even skeptical, acerbic writer and literary critic H.L. Mencken, no friend of religion, praised the King James Bible as "probably the most beautiful piece of writing in all the literature of the world."

But, as the KJV itself might say, "how are the mighty fallen" (II Samuel 1:27). Today hundreds of new English translations abound, as modern readers seek writing devoid of "thees" and "thous" that they hope will be easier to understand. The KJV has been surpassed as a mainstay of Protestant congregations by 20th-century translations such as the New International Version and the New Revised Standard Version. They're joined by many others, including "themed" Bibles aimed at children, teens, environmentalists, patriots, or just about any identity group.

Some versions, often called "dynamic equivalencies," don't attempt a literal, word-for-word translation, instead conveying what the translator sees as the sense of the text in everyday English. Even looser translations, called "paraphrases," take more liberties as they try to capture the spirit of the passage using modern idioms (compare three translations of Psalm 1 on the facing page).

"We are now in an era in which there is no common translation" of the Bible, says Mr. Radner. The KJV has become "a literary relic," he says, used principally by only a few denominations. "The mainline churches don't use it at all," he says. "In fact, it's considered a little bit of an oddity."

"It's a fait accompli. The King James has lost its dominance in the life of the church," adds Thomas Kidd, senior fellow at the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. "We can never go back to the one translation."

Scholars have welcomed many newer translations, which are able to draw on new biblical research and better source materials – manuscripts unknown four centuries ago, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls.

But what's lost, Dr. Kidd adds, is the sense of one common text whose words help form a common vocabulary for Christians and the culture in general. In many churches, "When there's a Bible reading from the pulpit or in Sunday school many of the people who are following along [in their own Bibles] are not reading from the same translation anymore," he says. "It didn't used to be like that at all."

The KJV's 400th anniversary is a bit like the birthday celebration of a beloved elderly relative, says Timothy Beal, a professor of religion at Case Western Reserve in Cleveland and author of "The Rise and the Fall of the Bible." "There's this little poignancy in the celebration that maybe this isn't going to go on forever."

The KJV represents "the flagship" of "book culture, the print culture, and our modern idea of the book," Professor Beal says. "And that culture is in its twilight."

While the KJV is readily available online in digital form, "When we think of the King James Bible I don't think it's the image of an iPhone. It's that black, leather-bound book," he says. "We have this idea of it being intact and whole and going from Genesis to Revelation. In the digital world ... that's not the way we read texts."

The KJV was compiled from 1604 to 1611 by about 50 clergymen-scholars working in six groups at the behest of England's King James I, who hoped that having a common "authorized" translation would help heal the religious strife threatening to tear apart his country. It drew heavily on previous English translations, especially the work of exiled scholar William Tyndale, who had translated most of the Bible into English in the early 16th century.

"[W]e never thought from the beginning, that we should need to make a new Translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one," wrote the translators in a preface to the first edition (no longer included), "but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principal good one.... [T]hat hath been our endeavor, that our mark."

It is translation, the preface goes on to say, that "openeth the window, to let in the light; that breaketh the shell, that we may eat the kernel; that putteth aside the curtain, that we may look into the most Holy place."

Indeed, the KJV was not a translation at all, but a revision. "It was a patchwork quilt, with the finest elements of its former voices stitched together," says David Teems, author of "Majestie: The King Behind the King James Bible."

In a society in which literacy was still largely confined to an elite, the KJV was meant to be read aloud, to be heard and, with its rhythmic cadences and use of repetition, remembered. What the translators sought was not only accuracy – based on the manuscripts at hand – but euphony, harmoniously combining words to be pleasing to the ear. The members of the committees read their proposed translations aloud to one another.

The result was remarkable text.

"Suddenly God was accessible," Mr. Teems writes. "No longer hidden or obscured, he seemed to genuinely care. Worship was no longer the remote procession of mystical events."

The writing styles ranged from earthy and sensual to lofty and poetic – the same wide range exhibited by Shakespeare who, during the same period the translators were toiling in anonymity, wrote some of the greatest plays in the English language, among them "King Lear," "Othello," and "Macbeth."

For Beal, modern translations, while essential to scholars, can reduce a passage "to a simple, straightforward meaning when the text isn't simple and straightforward: It's poetic. Poetry is rich and complex and poly-vocal: It has many different voices and images for different readers – many different possible meanings."

The language was often elevated, but for a purpose. "It might not be the way you talked in the marketplace, it was the way one talked religiously," Radner says. "It was the way one prayed. It was the way one preached." A barely educated Methodist preacher in the 18th century knew the Bible by heart and "could be extraordinarily rhetorically sophisticated by having learned and memorized the King James Bible," he says.

Radner, an Episcopal priest who has returned to using the KJV alongside the Revised Standard Version, says some looser modern translations pose problems. "You're never really sure how close these are to the actual words and sentence structure of the originals," he says. "You can be sure that the KJV tries very hard to do that. That's one reason why it's still useful."

At solemn occasions, many people unfamiliar with the KJV – or any Bible – want to hear from it. Psalm 23 ("The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want...") is a favorite at memorial services. "Modern language is very easy to read but in some people's minds takes away the power of those Elizabethan words that made it come alive," says Gary Davidson, senior vice president and Bible group publisher at Thomas Nelson Inc. in Nashville, Tenn., the leading publisher of the KJV. The 23rd Psalm, in the KJV, "just does something to your spirit when you hear it," he says. A more modern translation "leaves you a little flat, if you ask me."

Though sales of other Bible translations dipped last year, Mr. Davidson says, the KJV saw an 11 percent increase. "There's still a huge following," he says. "It's really near and dear to the heart of many people."

For Michael Hamilton, chairman of the religion department at Principia College in Elsah, Ill., the KJV represents "home base."

"It's the Bible that I use every day," he says. "It becomes part of you. Somehow its words and its phrases become part of your vocabulary of thought. It's the Bible that, if I read another translation, I always refer back to. [I want to know] 'how does the King James Bible say this?' "

No matter what translation readers use, Bible readers should feel assured that they will find the inspiration they seek, Davidson says. "The Holy Spirit will help you understand. That's what inspires you, the Holy Spirit. The words come off the page and you apply them to your life."

---

To receive Monitor recipes weekly sign-up here!

THE WORD IN TRANSLATION

Different translations of a Bible passage can lead to quite different reading experiences. Compare these three translations of Psalms 1:1-3, for example:

The King James Version (1611):

Blessed is the man that walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly, nor standeth in the way of sinners, nor sitteth in the seat of the scornful.

But his delight is in the law of the Lord; and in his law doth he meditate day and night.

And he shall be like a tree planted by the

rivers of water, that bringeth forth his fruit in his season; his leaf also shall not wither; and whatsoever he doeth shall prosper.

Contemporary English Version (1995)

God blesses those people who refuse evil advice and won’t follow sinners or join in sneering at God.

Instead, the Law of the Lord makes them happy, and they think about it day and night.

They are like trees growing beside a stream, trees that produce fruit in season and always have leaves. Those people succeed in everything they do.

“The Message” (1993)

How well God must like you – you don’t hang out at Sin Saloon, you don’t slink along Dead-End Road, you don’t go to Smart-Mouth College.

Instead you thrill to God’s Word, you chew on Scripture day and night.

You’re a tree replanted in Eden, bearing fresh fruit every month,

Never dropping a leaf, always in blossom.