Walking in the path of the Harlem Renaissance

Lawrence Henderson, a Harlem native and leader of the Soul of Harlem tour, stands near the “Planet Harlem” mural, Nov. 16, 2023.

Ken Makin

New York

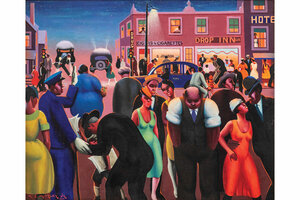

Tour guide Lawrence Henderson stops to admire his favorite mural, “Planet Harlem.” Artist Paul Deo’s work is peopled with a galaxy of Black stars –limitless luminaries in politics, entertainment, and resistance.

Mr. Henderson, a former service member and prison guard, says his eyes light up every time he sees this work of art. “Most murals you see have a particular theme, but this covers everything!” he says during a recent three-hour walking tour.

“Harlem loves its heroes,” Mr. Henderson says. One way to learn about the neighborhood that inspired artists and writers, activists and poets, is by walking among the streets now named for many of them. The fruits of that inspiration will soon be on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, when it presents “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism.” Opening Feb. 25, the exhibit will be New York City’s first focus on the renaissance since 1987.

Why We Wrote This

The Harlem Renaissance is the subject of a new exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Our cultural commentator relished his time walking the same streets that sheltered Langston Hughes, Malcolm X, and Alain Locke.

One hundred years after its launch, the Black arts renaissance remains relevant, whether it’s inspiring the next generation of artists or providing a gateway to a proud cultural past. The Met exhibit not only taps into this sense of Black pride, but also draws from institutions with histories as radical as the art it plans to display.

The Met exhibit seeks to reframe the Harlem Renaissance as “the first African American-led movement of international modern art,” the museum said in a press release. Organizers plan to explore how Black artists portrayed city life in the 1920s-1940s – in the early part of the Great Migration, “when millions of African Americans began to move away from the segregated rural South.”

It will feature over 160 works of painting, sculpture, photography, film, and ephemera, some of which are on loan from historically Black colleges and universities such as Clark Atlanta University and Howard University. Danille Taylor, director of Clark Atlanta’s art museum, which donated a quintet of pieces, believes that this exhibit is a commentary not only on Black life, but on legacy as well.

“I think these exhibits are educational. They provide physical evidence of the past, so that the past can be in dialogue with the present, and the present can be in dialogue with the past,” says Dr. Taylor in a phone interview. “[The Harlem Renaissance] had the New Negro, now we have Black Lives Matter, and they’re very much the same. We are human and we demand to be seen.”

Harlem has exhibited that message for generations, through historians, street vendors, and a collective consciousness. “Planet Harlem,” the apple of Mr. Henderson’s eye, is reflective of the adaptability of art beyond the confines of a museum. Mr. Deo himself is cognizant of protecting the people’s art, calling for his mural to gain “landmark status.”

Locke, Hughes, and Harlem’s “Godfather”

It’s hard to imagine that for the first 200 years of its existence, Harlem was undeveloped farmland. And yet, even in its modern incarnation, the city still has tillers – from street vendors to artisans to bakers.

The father of the Harlem Renaissance was Alain Locke. He was a writer and a dreamer. His first anthology, “The New Negro: An Interpretation,” was published in 1925. It was a collection of works from dynamic artists and analysts such as Zora Neale Hurston, Countee Cullen, and W.E.B. Du Bois. As Locke put it in his essay, this was a period of renewal, of self-respect, and of self-dependence among Black people.

Harlem has always been in the process of healing. Its current battles and sources of pride are all on display during one of Mr. Henderson’s excursions. The Harlem Hospital Mural Pavilion greets onlookers with a trio of images, for example. There’s a picture of Cab Calloway at the Cotton Club; a picture of Black professionals, or as Mr. Henderson puts it, “Black excellence”; and a depiction of the Great Migration.

In Locke’s anthology, there is an essay from historian and writer Arturo Schomburg titled “The Negro Digs Up His Past.” With so much talk of renaissance and rebirth, Schomburg focuses on another R-word: restoration. “History must restore what slavery took away,” he writes, “for it is the social damage of slavery that the present generations must repair and offset. So among the rising democratic millions we find the Negro thinking more collectively, more retrospectively than the rest.”

Schomburg, whose name is on Harlem’s Center for Research in Black Culture, took his own message to heart. His library of Black works, which grew beyond the capacity of his home, was shared with a division of the New York Public Library that eventually became the Schomburg Center. Years later, his life and legacy continue to grow like a tree planted by the rivers of water.

In the Schomburg Center, there is a lobby named after Langston Hughes, which honors both of Harlem’s heroic historians. The lobby is literally Hughes’ final resting place: His ashes are buried underneath. There is a mural of sorts in the floor – a cosmogram linking Hughes and Schomburg with African ritual ground markings and other measurements. The center says the cosmogram is “weaving a web of connections between people of diverse cultures and backgrounds, the past and the present.”

During the course of the journey through Harlem, Mr. Henderson also engages tourists with talk about gentrification. The demographics of Harlem are changing. Black residents made up 90% of Central Harlem in the 1980s. In 2021, it was 44%.

An online petition from the New York Interfaith Commission for Housing Equality has a two-word message: “Save Harlem!” The group’s angst stems from an Ivy League institution, Columbia University, and private developers “aiming to destroy and displace thousands of Harlem’s residents.”

Mr. Henderson stands in front of the Lenox Terrace apartments and talks about the infamous Ellsworth Raymond “Bumpy” Johnson, the “Godfather of Harlem.” Johnson had South Carolina roots as well; he was born in Charleston on All Hallows’ Eve in 1905. The historic terrace was where he called home, and even with his criminal reputation, he was beloved by Harlem.

With the rising cost of housing – and employment – Harlem is hanging on for dear life. A vendor named Divine Styles proudly displays what equates to a curbside bookstore. There is a red, black, and green flag adorning the stand, and the mutuality between the vendor and Mr. Henderson is apparent even before one sees the similarly colored flag on the tour guide’s jacket. The Pan-African flag, also known as the RBG flag, symbolizes unity among people of African descent.

Divine Styles laments that his stand is always on the move, most recently forced out of his old spot by the new Victoria hotel. Nevertheless, true to Harlem, he remains optimistic.

“I love this corner,” he says. “My goal is to publish a book about all of the vendors on 125th Street.”

“Before they’re gone?” Mr. Henderson asks.

“We’re not going to let that happen,” Mr. Styles responds. “There should be a Black preservation – something to protect the vendors.”

“By Any Means Necessary”

It’s hard to fathom that after hundreds of years, there are parts of Harlem that are still underdeveloped. But the tillers persevere. And so does Harlem’s soul.

There is an unfinished mural with a host of celebrity images and four words that Malcolm X made famous – “By Any Means Necessary.” The artists? Pipps and Marissa, the former of whom was seemingly inspired by Gladys Knight, the “Empress of Soul.”

The mural, which was commissioned by a community outreach program, has a quintet of images in which a famous elder is inspiring a young person. There’s Muhammad Ali fitting a boxing glove on a youngster and Serena Williams offering a tennis lesson. On the other side, there’s LeBron James shooting hoops with a young protégé and Simone Biles instructing a future gymnast. At the heart of the piece is Malcolm X, reading a book to a child.

“They wanted to show change-makers in a particular field working with youth, pretty much, you know, passing the torch,” Pipps says. “I want Malcolm to be in the center because he’s from this community.”

The highlight of the project might have been the community paint day on Nov. 14, when onlookers and other participants were allowed to paint the mural.

“We had small kids here, elderly people, people stopping at the bus stop. Everyone was allowed to paint,” Marissa says. “I love inspiring people and letting them know they can do whatever.”

For this journalist, one of the highlights of the tour is a stop for red velvet cake from Cake Man Raven. His bakery is about four minutes from the “Planet Harlem” mural, and it is a confectionary to the stars. His clients, he says, have included Jay-Z and Whoopi Goldberg. The crimson in that delectable delight is a reminder of the power of migration. Red velvet cake is commonly thought of as a Southern delicacy, and the Cake Man, from Florence, South Carolina, is quick to note his roots.

As the tour comes to a close, the marquees for the Apollo Theater and the former Victoria Theater are a reminder of Harlem’s imposing history. At night, their neon lights illuminate the sky and one’s imagination. In daylight, the cultural landmarks represent the thin line between struggle and progress.

A block or so down the street, another legend adept at migration comes to the forefront – Harriet Tubman, whose memorial sits at a fork in the road. It is a striking piece, replete with distinctive roots that represent slavery. Her skirt is decorated with images of enslaved people she led to freedom. It is worth mentioning that Tubman is one of America’s great generals due to her leadership in the Combahee River Raid in the Lowcountry of South Carolina.

The duality of Harlem – of Black struggle and progress – comes through in Mr. Henderson’s closing words. There is lament and love.

“People in Harlem, they complain about things changing, and rightfully so. But we had Harlem for 100 years. We claimed it and we let it slip through our hands,” he says. “There are many reasons. We couldn’t get loans from banks. Systemic racism.

“It hurts to see Black people down and out,” he adds. “Knowing our potential, knowing how much we accomplished.”

As Mr. Henderson departs, his words resonate. So do the words of Locke: “In the very process of being transplanted, the Negro is being transformed.”