Sounding together at the Spring for Music festival

The now-annual Spring for Music festival is a place for orchestras to showcase their talent and inventiveness and was held at Carnegie Hall.

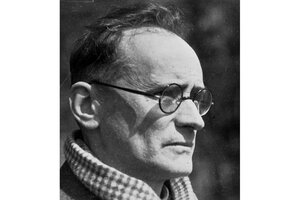

Anton von Webern, c. 1935

Newscom

Sure, I might not have wrinkles yet and my joints are still pretty flexible, but there are definitely disadvantages to being young in the 21st century. For one thing, I don’t really know what it’s like to not be able to Google something. Second, I can’t ever say things like, “Those 80s were pretty crazy.” But another reason why my youth is a drawback is a reason I can probably share with people who I don’t share these other two reasons with. Though I can instantly access the newest modern pieces of music through a few clicks of the keyboard, I will probably never have the experience of wearing a ball gown, getting in a horse-drawn carriage, and riding to the premiere of the symphony of the latest, famous composer like they (most likely) would back in teh 19th century. Symphonies, if one were to look back on a timeline of musical history, are benchmarks of aural progression through the times. Mozart’s 40th , Beethoven’s 5th , Dvorak’s 9th , Shostakovich’s 5th , Mahler’s 2nd … these are all protruding figures in the landscape behind us. However, despite the absence of petticoats in my closet, the premieres I will go to in my lifetime will probably have the same emotions that premieres of symphonies had in previous centuries—and it’s not just because of the change in wardrobe and customs—but the change in the art of the symphony itself.

The now-annual Spring for Music festival was held last week, with concerts held almost every night from May 6th to May 14th . The festival is a place for orchestras to showcase their talent and inventiveness and was held at Carnegie Hall. The S4M’s mission statement is: “Spring for Music provides an idealized laboratory, free of the normal marketing and financial constraints, for an orchestra to be truly creative with programs that are interesting, provocative and stimulating, and that reflect its beliefs, its standards, and vision.” The orchestras that were featured in the 2011 festival were the Albany Symphony, the Dallas Symphony, the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal, the Oregon Symphony, the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, and the Toledo Symphony. The performances ranged from Beethoven to Stucky, from Gabrieli to Vaughan Williams, and from Britten to Adams. While the programs were infested with modern music and inventive choices, almost all of the orchestras played a symphony. In fact, the Orchetre Sympohnique de Montreal played seven symphonies during their program, the one that led the festival to an end.

The entire Spring for Music festival is something that hasn’t been done before on the same scale. It inspired me and made me want to live in New York or have my own private jet really bad. But what really got me thinking was the program of the Montreal orchestra led by Kent Nagano. He themed it to describe the evolution of the symphony—in fact, the title of his program was “Evolution of the Symphony.” Weird. In his program were symphonies, some for orchestra and some for sections, by Gabrieli, Bach, Webern, Stravinsky, and Beethoven. But, contrary to what his title might suggest, he did not perform them in chronological order. Nagano chose to separate the large orchestral works with sinfonias by Bach played by Angela Hewitt on the piano. Gabrieli’s piece was Sacrae Symphoniae for brass and demonstrates the beginnings of the form in the Renaissance. Webern’s Symphony, Op. 21, the raw and almost conversational-between-notes piece, and Stravisnky’s Symphonies of Wind Instruments, the triumphant yet slightly unsettling work, represented the early 20th century influences on the form while Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, one of the most iconic symphonies of all time, closed out the program. It was definitely risky, but it paid off. Tweets from the concert said things like “Fascinating programming tonight from the Montreal Symphony…” (Fred Child of APM Classical) and “the lack of lobby space turns into a seriously interesting health and safety issue when the place is as full as Carnegie is tonight” (kacareton). With this challenging and dense program, Nagano asked the questions (interviewed by WQXR), “Why is a symphony relevant for today? Or is it relevant for today in the 21st century? What exactly would be the role of classical music in the future? Is it simply a group or genre of music only for an elite, selected, educated, sophisticated audience? Or is it something that’s much more meaningful to the general population?” In the same WQXR interview, Nagano said that he chose these specific works because they shy away from our stereotypical idea of a symphony. Though the first question I quoted was meant to inquire about the organization “symphony,” it made me think of why a piece symphony would be relevant today. As new CDs and albums are released, it seems as though intricacies of contemporary music are being focused on instead of the grandness of Romantic or early 20th century music. Instead of composers announcing the premiere of their newest symphony, it seems more common to hear about the release of chamber works, contemporary operas, or one movement orchestral tone poems. Is the art of the symphony as a work dying out? I rarely hear word of a modern symphony about to be premiered by a popular composer. The term is nowhere near dead, but, unlike the towering masterpieces that the members of the pantheon of symphonists composed, the walls of the intangible Modern Music Hall of Fame aren’t covered in symphonies. However, I say no—maybe we’ll just have to change the term.

A symphony is defined as an orchestral work most often written in the sonata principal. Because the word “symphony” (which comes from “syn,” together, and “phone,” sounding) is such a broad term, it was often used in the pre-Baroque ages as a label for many different types of musical composition. But that changed around the 18th century. While the symphony began as a three movement medium, Mozart and Haydn began to add a fourth movement in the middle which quickly became the norm. Beethoven made the symphony the grand mass that it is today, giving the world nine symphonies (he couldn’t beat Mozart by the around 40 point lead he had on Ludwig), and practically every single one is now a classic repertoire member. Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique was groundbreaking, as were Tchaikovsky’s and Dvořák’s. Gustav Mahler brought the art into the 20th century strongly, composing almost 10 symphonies (one even needs around 1000 performers). Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Rachmaninoff, Sibelius, and Nielsen were brought into the mix soon after. The symphony isn’t only a form though—it represents a great achievement in music; one expects to hear impressive and striking sounds when going to a performance of a symphony.

If these great, massive works that now bombard the programs of orchestras everywhere happened only a handful of decades ago, why are the releases that make up most of the hype in the classical world today (in America, at least) not symphonies? While there are most definitely modern symphonies that are called symphonies, such as ones by Christopher Rouse, John Corigliano, or Aaron Jay Kernis, we often don’t hear of symphonic premieres that meet the statures of the ones decades ago. Perhaps this has to do with the downsizing of classical audiences anyway, but operatic premieres often are sold out and modern chamber music/solo piece premieres in big cities draw large crowds, especially premieres of well-known composers. But don’t lose faith—we are nowhere near losing the art form that spawned from the symphony. That’s just the whole point of it; the forms that are being practiced today are kin to the symphony, but can’t be classified as such. Sure, some of it has to do with composer’s brainchild has changed. Sometimes we are going to large scale symphony premieres, but we just don’t know it.

Examples of these symphony-esque art forms are all around us. One of John (Coolige) Adam’s most famous works, Harmonielehre, is quite similar to a symphony. While it is not classified as one, the piece shares many similarities with the form we have come to know. It’s divided into three movements (unnamed, “The Anfortas Wound,” and “Meister Eckhardt and Quackie”) that follow a similar mood progression that symphonies do. Naïve and Sentimental Music is Adam’s real, official, categorized symphonic work (while the classification of Harmonielehre is a bit iffy). However, when I listen to N&S, I don’t think “Oh, just off to listen to that Adam’s symphony.” When I’m listening to that piece, I’m listening to Naïve and Sentimental Music and nothing else. Another orchestral form that parallels symphonies is the tone poem. Famous tone poems from centuries past include Debussy’s Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, Liszt’s (who created the term) Totentanz, and Schoenberg’s Pelleas und Melisande. The tone poem is a wide concept—it’s usually in one movement (sometimes close to or longer than symphonies themselves) and is inspired by another work of art or life. There are countless modern tone poems and similar art forms, such as Georg Friedrich Haas’s In Vain, the 75 minute piece for 24 musicians that is chilling, watercolor infested, and hypnotizing (it’s not exactly a tone poem, but it’s pretty much the same thing). Other works of similar style include Milton Babbitt’s Relata I&2, Iannis Xenakis’s Metastasis, and John Luther Adam’s In the White Silence.

Now, when I think about it, I listen to a lot more symphonies than I realize. No, maybe Haydn and Mozart wouldn’t open up their silk-covered arms to the pieces that have spawned form their creations, but hopefully they would be able to see the timeline. Perhaps modern composers have strayed away from the traditional symphony form just to break away from the mold set in stone. Maybe composers feel bored by the limits of a four movement symphony and can feel freer inside a one movement landscape. But, looking back on Kent Nagano’s questions he posed in the WQXR interview, perhaps composers today are just keeping things relevant. To an audience member not familiar with classical music, a one movement canvas is a lot more approachable than a daunting, Beethoven-esque symphony. Though they may be similar in length, tone poems are easier to become familiar with. Also, the beginnings of centuries are always transition periods, and we are definitely transitioning. To what, I don’t know, but it’s like gardening in one large bed versus four smaller ones—a composer has more space and chances to find where they are trying to go inside a musical form that isn’t restricted by men who lived centuries ago. Tone poems and modified symphonic forms are more cultivating environments for musical modes and ideas still in the works. The composers today are taking care of the grandchildren that will grow up to change the world tomorrow. Should their daycare be the most nurturing place we can find?

I don’t own ball gowns that women wore in the 19th century, and I probably never will own any (apart from the costume-end of my closet). But I can still go to premieres, and they might be symphonic ones to. The program might not give that away, but I know that somewhere those other three movements are looking down, proud. Maybe.

Elena blogs at Neo Antennae.

------------------------------------------------------------

The Christian Science Monitor has assembled a diverse group of music, film, and television bloggers. Our guest bloggers are not employed or directed by The Monitor and the views expressed are the bloggers' own and they are responsible for the content of their blogs. To contact us about a blogger, click here.