Kids turning to cellphone for Internet; it's tough on parent oversight

The number of teens and tweens accessing the Internet via cellphone is growing, a new survey says, posing bigger problems for parents who like to keep tabs on their kid's Internet activities.

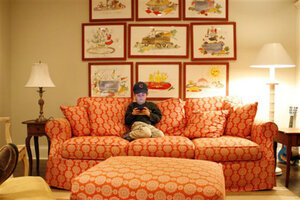

Peter Conkey, 6, plays on his iPod Touch in his Illinois home March 11. A new Pew report indicates that Peter's generation will be even more likely to use mobile devices, including smartphones, as their main means of accessing the Internet.

Associated Press

Chicago

Keep computers in a common area so you can monitor what your kids are doing. It's a longstanding directive for online safety – but one that's quickly becoming moot as more young people have mobile devices, often with Internet access.

A new report from the Pew Internet & American Life Project finds that 78 percent of young people, ages 12 to 17, now have cellphones. Nearly half of those are smartphones, a share that's increasing steadily – and that's having a big effect on how, and where, many young people are accessing the Web.

The survey, released Wednesday, finds that one in four young people say they are "cell-mostly" Internet users, a percentage that increases to about half when the phone is a smartphone.

In comparison, just 15 percent of adults said they access the Internet mostly by cellphone.

"It's just part of life now," says Donald Conkey, a high school sophomore in Wilmette, Ill., just north of Chicago, who is among the many teens who have smartphones. "Everyone's about the same now when it comes to their phones — they're on them a lot."

He and other teens say that if you add up all the time they spend using apps and searching for info, texting and downloading music and videos, they're on their phones for at least a couple hours each day — and that time is only increasing, they say.

"The occasional day where my phone isn't charged or I leave it behind, it feels almost as though I'm naked in public," says Michael Weller, a senior at New Trier High School, where Conkey also attends. "I really need to have that connection and that attachment to my phone all the time."

According to the survey, older teen girls, ages 14 to 17, were among the most likely to say their phones were the primary way they access the Web. And while young people in low-income households were still somewhat less likely to use the Internet, those who had phones were just as likely — and in some cases, more likely — to use their cellphones as the main way they access the Web.

It means that, as this young generation of "mobile surfers" grows and comes of age, the way corporations do business and marketers advertise will only continue to evolve, as will the way mobile devices are monitored.

Already, many smartphones have restriction menus that allow parents to block certain phone functions, or mature content. Cellphone providers have services that allow parents to see a log of their children's texts. And there are a growing number of smartphone applications that at least claim to give parents some level of control on a phone's Web browser, though many tech experts agree that these applications can be hit-or-miss.

Despite the ability to monitor some phone activity, some tech and communication experts question whether surveillance, alone, is the best response to the trend.

Some parents take a hard line on limits. Others, not so much, says Mary Madden, a senior researcher at Pew who co-authored the report.

"It seems like there are two extremes. The parents who are really locking down and monitoring everything — or the ones who are throwing up their hands and saying, 'I'm so overwhelmed,'" Madden says.

She says past research also has found that many parents hesitate to confiscate phones as punishment because they want their kids to stay in contact with them.

"Adults are still trying to work out the appropriate rules for themselves, let alone their children," Madden says. "It's a difficult time to be a parent."

And a seemingly difficult time for them to say "no" to a phone, even for kids in elementary school, where the high-tech bling has become a status symbol.

Sherry Budziak, a mom in Vernon Hills, Ill., says her 6-year-old daughter has friends her age who are texting by using applications on the iPod Touch, a media player that has no phone but that has Internet access.

She draws the line there. But she did get her 11-year-old daughter an older model iPhone last fall, so she can stay in touch with her. Budziak, who works in the tech field and understands the ins and outs of the phone, set it so that the sixth-grader can text, make and receive phone calls and play games that her parents download for her.

"So we're on the conservative side, by far," she says.

Budziak also tells her daughter and her daughter's friends that it's Mom's phone, not her daughter's. It means that she and her husband monitor texts on the phone any time they like.

Does their daughter protest about all the restrictions? Occasionally.

"But she wants a phone so badly that it doesn't matter right now," Budziak says. "Having a phone was better than having no phone at all."

Mark Tremayne, an assistant professor of communication at the University of Texas at Arlington, says he and his wife put off getting their son a smartphone longer than most— until his 13th birthday, which is quickly approaching. They plan to monitor it, having already discovered a few "surprises" when checking the Web surfing history on his iPod Touch.

On one hand, Tremayne says it's the sort of stuff he used to look up in books and magazines when he was 13.

"It's pretty clear that kids will do what kids will do," he says. But he acknowledges that having a mobile device can make it that much easier to access.

The key, he says, is to talk to his son about it, and that's what many other tech and communication experts also advise.

"I don't think the technology itself is bad. The benefits vastly outweigh the risks. But parents do need to be aware," says Daniel Castro, a senior analyst with the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a research and education think tank based in Washington, D.C.

"Part of it is simply asking, 'What are you doing, and why?'"

Too often, he and others say, adults don't fully understand how the smartphones work — or how their kids might use them differently than they do.

So guidance from parents, teachers and other adults can be lacking, says Danah Boyd, a senior researcher at Microsoft Research who specializes in teens and their tech-driven communication.

"For the last decade, too much of the online safety conversation has focused on surveillance. Surveillance will not help in a world of handhelds, but conversation will," says Boyd, who's also a research assistant professor of media, culture, and communication at New York University.

She points to research by Henry Jenkins, the director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has long encouraged parents, schools, and after-school programs to focus on how to navigate the online world — from developing judgment about credible online sources to using high-tech skills to help build community and pool collective knowledge.

At the Conkey household in suburban Chicago, brothers Donald and Harry know their parents track the music they buy and might look at their Web surfing history when borrowing their sons' laptops. Mom Brooke Conkey acknowledges that she also may glance at the occasional text.

"Oh yeah, she'll look over our shoulders and she'll want to know who we're talking to — and that's to be expected," says Harry Conkey, a high school senior. "It's a parent. It's natural to want to know who your kids are talking to."

His parents don't use filters of any kind because, while there's been the occasional "mistake" when downloading or surfing on their phones or laptops, Mom and Dad think that's just part of learning and growing up. That may change, however, with their 6-year-old son Peter.

"I think that things will get trickier as time goes on," Brooke Conkey says. "And I think things will be easier to get to — the naughty things. So I think I probably would be more proactive than I was with the older boys."

It's a balance, she says, because she and other parents also realize that smartphones and other mobile devices are only likely to become an even more integral part of life and learning. At least at the college level, some schools are seeing the benefit of mobile surfing, and encouraging it, too.

Last fall, Stephen Groening, a film and media studies professor at George Mason University in Virginia, taught a class that examined "cell phone cultures." Students did much of the class work using phones — creating video essays, taking pictures, texting, and tweeting.

"I've had students tell me that they bring their cell phones in the shower with them. They sleep with them," Groening says, noting that he never knew a student attached to a laptop in that way

In New Jersey, Seton Hall University gives incoming freshman a free smartphone for the first semester. Among other things, they use them to help them navigate campus, connect with other students and follow campus news that streams on the SHUmobile app.

Kyle Packnick, a freshman at Seton Hall, liked having one of the phones and said they're particularly helpful for students who don't come to school with a smartphone.

But he also thinks people his age could do a better job setting their own limits with technology — and is grateful that his parents didn't even allow him to text on his cell phone when he was in high school. He was only allowed to make phone calls.

"At the time, I definitely wasn't happy about it," the 19-year-old says. But now he feels he's less dependent on his phone than his peers.

Pew's findings are based on a nationally representative phone survey of 802 young people, ages 12 to 17, and their parents. The report, a joint project with the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, was conducted between July and September last year. The margin of error was plus-or-minus 4.5 percentage points.