Wayne Miller dies, leaves legacy of photos and forests

Wayne Miller dies: His photography documented moments of World War II, black Americans living on Chicago's south side in the late 1940s, his family and redwood forests. Some of Wayne Miller's images are now held in collections at museums around the country.

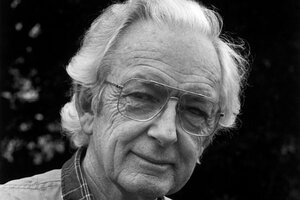

Wayne Miller dies: This undated photo provided by his family shows renowned American photographer Wayne F. Miller. Miller, who produced some of the most indelible combat images of World War II and created a ground-breaking series of portraits chronicling the lives of black Americans in Chicago, died Wednesday, May 22, 2013.

Joan B. Miller/AP

ORINDA, Calif.

Photographer Wayne F. Miller, who created a ground-breaking series of portraits chronicling the lives of black Americans in Chicago after serving with an elite Navy unit that produced some of the most indelible combat images of World War II, died Wednesday.

Miller was also known for his work as a curator on an international photojournalism exhibition called "The Family of Man" and for contributing the photos to Dr. Benjamin Spock's "A Baby's First Year." He had lived in Orinda for six decades and become ill only in the last weeks of his life, his granddaughter Inga Miller said.

Born in Chicago, Miller trained for a career in banking but became a photographer when famed fashion photographer Edward Steichen picked him to be part of the military unit assigned to document the war. While assigned to the Pacific theatre, he took some of the first pictures of the atomic bomb-devastated Hiroshima.

His best-known wartime photograph shows a wounded pilot being pulled from a downed fighter plane. Miller had been scheduled to be aboard the plane before it was shot down, and the photographer who took his place was killed, according to Inga Miller.

After returning home to Chicago, Miller spent two years in the late 1940s on the city's south side capturing the experiences of black residents, many of whom had moved north during the war in search of jobs and the promise of civil rights. The originals from his "The Way of the Northern Negro" series are now held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim Museum and the Smithsonian Institution.

"He was tired of what a good job photography was doing of showing the way we were destroying each other and he decided to come back and have the medium connect people in a more meaningful fashion," said Paul Berlanga, director of Chicago's Stephen Daitler Gallery. "He wanted to bring the white and black races together, and thought to make a photo documentary to introduce black Chicago to white Chicago and to white America."

While he mostly turned his lens on ordinary Americans, his subjects for the series included emerging stars such as Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington and Eartha Kitt.

During the early 1950s, Miller reunited with Steichen in putting together "The Family of Man," a Museum of Modern Art exhibit featuring hundreds of portraits by photographers from all over the world. A book of the same name based on the exhibit sold more than four million copies. An iconic photograph of Miller's that was part of the exhibit showed his son David being delivered as a baby by his grandfather. It was included in a phonographic time capsule Carl Sagan put together that was launched with the Voyager spacecraft in the late 1970s.

Miller also produced an intimate book of his photography called "The World is Young."

He spent the next several decades as a photojournalist for Life, Ebony, the Saturday Evening Post and other magazines. For six years, he was president of Magnum Photos, a photographer's cooperative. Magnum's current president, Alex Majoli, praised Miller as a pioneer who "paved the ground for the rest of us who tried to depict the streets, the real life."

"It might have seemed like golden years for photographers now, but he had to invent himself in many ways, a character trait I highly appreciate in people," Majoli said.

Miller stopped working as a professional photographer in the mid-1970s, but he found a new passion crusading for the preservation of California's redwood forests. He and his wife, Joan, restored a clear-cut patch of forest and helped lobby for the passage of laws that provided incentives for landowners to protect rather than log trees. According to his family, the forest was Miller's main photographic subject after his retirement.