'Like Father, Like Son' cuts to the heart of what it means to be a parent

'Like Father, Like Son' follows two families whose sons were switched at birth.

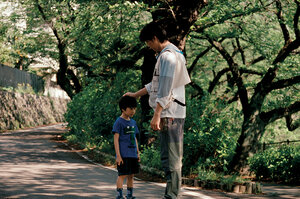

Ryota (Masaharu Fukuyama) is a Tokyo architect with little time for son Keita (Keita Ninomiya). A surprise is in store.

IFC Films

“Like Father, Like Son,” the new movie from the Japanese writer-director Hirokazu Kore-Eda, is about two couples who discover that their 6-year-old sons were switched at birth. In lesser hands we’d be watching a soap opera.

Ryota and Midori Nonomiya (played by Masaharu Fukuyama and Machiko Ono) live in an expensive, modern Tokyo high-rise with their only child, Keita. Yudai and Yukari Saiki (played by Lily Franky and Yoko Maki), by contrast, live in a small apartment above the family’s appliance shop with their three children, including 6-year-old Ryusei.

When the rural hospital where the boys were born contacts the parents to inform them of the mistake, both parties are poleaxed by the news. Talk of accountability and lawsuits (mostly from Yudai) shade into deeper discussions about what exactly should be done. At first there are get-togethers in malls and in each other’s homes; then the boys, innocent of the mix-up, are swapped on weekends in preparation for the switch.

The evolving decision about what to do cuts to the heart of what it means to be a parent – specifically a father, since much of the movie focuses on Ryota’s transformation from distant dad to caring father. Baldly put, it’s a movie about nature versus nurture.

It is also – and this is the film’s central weakness – a class-based fable. In Kore-Eda’s view, the Nonomiyas’ wealth makes them, or at least Ryota, who is a successful workaholic architect, less warm and fuzzy than the Saikis, who take splashy family baths together and go kite flying.

This point is driven home in the film’s very first scene, in which we see Keita being interviewed for his entrance into a posh private school. He has been schooled by a “cram coach” in how best to respond to the examiner’s questions. (For example, the boy tells the committee, falsely, that he bonded with his father while flying kites.)

Ryota, not a bad man, indulges his son, but he doesn’t set aside much time for him. He leaves most of the caring to Midori, who at first comes across as a dutiful homemaker. (He reminds her to make the dinner noodles al dente as if he were issuing a company directive.) When he hears the news that Keita is not his birth son, his response is, “Now it all makes sense.” He means that the boy’s lack of competitive instinct to him has always seemed vaguely suspect. These are the words that come back to indict him when Midori, who grows in strength as the enormity of her quandary sinks in, throws them back in his face. (That face is a bit impassive. Fukuyama, a pop singer/actor, is not particularly expressive.)

By contrast, the Saikis have a ramshackle, communal lifestyle with lots of fun and games. Their reaction to Ryota’s suggestion that he buy Ryusei and raise the two boys together is so deeply offensive to them that the two men almost come to blows. (The issue is never raised again.) Keita goes kite flying with his “new” father; he bonds with the family. Ryusei, in his outings with the Nonomiyas, is less indulged.

Kore-Eda directs in a spare, unforced style that leaches much of the potential slobberiness from this story; and yet the film’s rich/cold versus the not-so-rich/warm dichotomy is inherently sentimental. I’m not sure why he chose to do it this way. Surely the film’s power would not have been diminished if he had simply presented the two families as equals on the success ladder. (It might have been more interesting if the wealthy family had been the warmer one – the parenting and custody issues would have been more complex if the wealthier couple was also the more loving one.)

Previously Kore-Eda has made movies about rived families that have centered on children, such as “Nobody Knows,” in which a mother abandons her kids, and “I Wish,” about parental divorce. Here he shifts the focus to the adults, and this often means the two boys get short shrift. Kore-Eda perhaps believes that children have an innate resiliency in these matters, and that, in the end, this is a movie about how a child makes a father out of a man. Well and good, I suppose, except that this, too, is a sentimentalism. Six years is certainly old enough for a child to register seismically such a wrenching family displacement. To pretend otherwise is blinkered.

Despite the film’s emphasis on Ryota’s transformation, the most piercing moment for me came in the scene in which his wife anguishes over her guilt in not realizing right away, as a mother, that Keita was not her birth son. At times like this, “Like Father, Like Son” ascends to dizzying emotional heights. Grade: B (Unrated.)