‘Loving Vincent’ prompts respect for the effort that went into hand-painted film, if not the result

In the movie about Vincent Van Gogh, the reproductions of the artist's paintings can’t possibly match the originals’ emotional fervor.

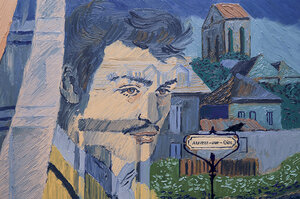

Some 65,000 frames were hand-painted for the Van Gogh biopic 'Loving Vincent.'

Good Deed Entertainment

“Loving Vincent” is billed as “the world’s first fully painted feature film,” and I have no reason to doubt the claim. The Vincent in the title of this very strange movie is the great Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh, and you would think he already had more than his share of biopics.

The most famous, of course, is Vincente Minnelli’s very fine “Lust for Life,” starring Kirk Douglas in one of his best seething performances. Maurice Pialat’s “Van Gogh” has its adherents, as does Paul Cox’s “Vincent,” which makes great use of the painter’s canvases and letters to his brother and benefactor Theo. There’s also Akira Kurosawa’s “Dreams,” featuring a segment with Martin Scorsese as Van Gogh – still my favorite piece of miscasting in all of cinema.

Best, perhaps, is Robert Altman’s rarely seen “Vincent & Theo,” starring Tim Roth as Van Gogh, one of the very few movies that demonstrates, without any romanticizing, the ferment that can underlie great artistry. It has some of the same tumultuous emotionality as Van Gogh’s paintings.

“Loving Vincent,” co-directed by Hugh Welchman and Polish animator Dorota Kobiela and co-scripted by Jacek Dehnel, is framed as a kind of “Citizen Kane”-style detective story focusing on Van Gogh’s frenzied final months in Auvers-sur-Oise, France, where, in 1890, he fatally shot himself. (The film’s title is derived from Van Gogh’s signoffs to his beloved brother in his letters – “Your loving Vincent.”)

Before we get into the substance of the film, attention must be paid to how its imagery came to be. (In a sense, style and substance in this movie are synonymous.) I always feel a little guilty about criticizing animated features because the painstaking work that goes into creating even a bad animated movie is so often staggering. “Loving Vincent” took seven years to complete and involved 125 artists hand-painting some 65,000 frames of film. About 130 of Van Gogh’s paintings are dynamically reproduced in the flow of images using this method, in which everything is first filmed as live-action and then rotoscoped with animation.

The scenario, if not the imagery, is fairly straightforward. Upon hearing the news of Vincent’s death, Armand Roulin (voiced by Douglas Booth), at the request of his postmaster father, Joseph (Chris O’Dowd), is tasked with delivering the last letter from Vincent (the Polish theater actor Robert Gulaczyk) to Theo. Armand reluctantly complies, only to discover that Theo, too, has died. He decides to stay in Auvers-sur-Oise and uncover what really happened to Van Gogh in the end. (Armand also acts as the film’s narrator.) In the course of his detective work, he encounters various villagers who all seem to have their own theories about the artist’s demise. Some even believe he was murdered. (This theory was actually put forth, without any definitive proof, in a celebrated recent biography by Gregory White Smith and Steven Naifeh.) As the townspeople take turns offering up their version of events, we recognize some of their faces from Van Gogh’s famous portraits, including Marguerite Gachet (Saoirse Ronan) and her father, Dr. Paul Gachet (Jerome Flynn), who treated Van Gogh in his last days.

The filmmakers resort to multiple flashbacks of Van Gogh’s life, which, unlike the present-day imagery, are exclusively in black and white – a mistake, I think, because the grayed-out effect drags down the look of the entire film, which is otherwise almost riotous with color.

But what exactly are we getting with this vast swirl of colorations, these 65,000 frames of rotoscoped reproductions? It’s kind of kicky to pick out all the paintings as the story ensues: “The Night Café,” “Wheatfield with Crows,” “Starry Night,” and many others. But in the end, we are viewing, at best, deft – and at worst, kitschy – renderings of great paintings. The reproductions can’t possibly match the originals’ emotional fervor. How could they?

There’s another problem here, which is especially typical of movies about great, tortured artists. The filmmakers want us to understand Van Gogh’s mind through his work, and while this approach certainly has its pop psych fascinations, it’s ultimately too glib. The correlation between how an artist lives his life, and the work he produces in that life, is too complicated, perhaps too unknowable, for such one-to-one connections.

Still, the fact that this movie, with its 65,000 painted frames, was even attempted, is daunting. It’s the kind of folly that demands a measure of respect, for the effort, if not altogether for the result. Grade: B- (Rated PG-13 (for mature thematic elements, some violence, sexual material, and smoking).