Indigenous children were abused in Canada. A film seeks answers.

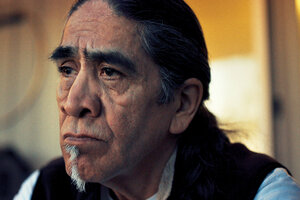

Ed Archie NoiseCat, father of “Sugarcane” co-director Julian Brave NoiseCat, grapples in the film with events from his past.

Emily Kassie/Sugarcane Film LLC

In 2021, in British Columbia, hundreds of unmarked graves were discovered on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. Established in 1893 as part of a government policy of forced assimilation of Indigenous children, and later run primarily by the Catholic Church, Kamloops was once the largest such school in Canada. Enrollment topped 500 in the 1950s.

The outrage fueled by this discovery sparked church burnings throughout the region. It also informs the documentary “Sugarcane,” which casts a woeful, compassionate eye on the sordid history of compulsory education of Indigenous Canadian children.

Directed by Emily Kassie and Julian Brave NoiseCat, the film is an indictment of a cultural tragedy; a testament to the steadfastness, against all odds, of the Indigenous community; and a plea for healing. Kassie is a veteran investigative journalist. NoiseCat is a celebrated writer whose estranged father, Ed Archie NoiseCat, an accomplished sculptor who struggled with alcoholism, figures prominently in the footage. The documentary’s furious emotional center is the disclosure of Ed’s secretive birth at the St. Joseph’s Mission residential school, where he was subsequently abused, to a mother who was raped by a priest. Only the chance discovery of the newborn by a milkman saved him from the infanticide that befell other such unwanted babies.

Why We Wrote This

“Sugarcane” casts a woeful, compassionate eye on the sordid history of compulsory education of Indigenous Canadian children, the Monitor’s film critic writes. In this powerful documentary, the survivors of atrocities want to move beyond their rage.

The stories disclosed by the survivors of these institutions are a litany of intergenerational sorrow. The schools, such as St. Joseph’s, with its connection to the Sugarcane Reserve, were often located far from Indigenous communities in order to enforce a sense of cultural and familial isolation. Tribal languages and dances were forbidden, family names were erased. Children were identified by number.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada asserted the nation’s system of segregated church-run residential schools, the last of which closed in 1997, constituted “cultural genocide.” It estimated that at least 4,100 students died while attending the schools, many from abuse and disease.

We see footage of Indigenous people from Canada as they convene in the Vatican to receive an apology from Pope Francis in 2022. Such dutiful acts can’t compare in emotional power to the many individual testimonies we witness. Willie Sellars – chief of the Williams Lake First Nation, who spearheaded the post-Kamloops investigation – is an absolute marvel of tenacity. So is Charlene Belleau, who in one scene ritually invokes the ancestors and spirits of the departed schoolchildren.

Perhaps the most complex figure in the film is Williams Lake First Nation former Chief Rick Gilbert, an outwardly genial man of dizzying contradictions (who died in 2023). He was sexually abused as a student at Kamloops, where his mother had been raped as a girl. After some prodding by his wife, Anna, he takes a DNA test, which establishes that his lineage includes heritage bearing the surname of one of the school’s priests. He can’t quite accept the results and wants more proof.

And yet, he and Anna are devout Catholics. Upon learning of the church burnings in the area, they preemptively stow away relics from their local chapel. Rick is among those who travel to the Vatican. Speaking of the atrocities, Anna says, “Don’t blame the church. We don’t hold Jesus accountable for that. People are people.”

I wish the filmmakers had delved more deeply into the ways in which the Gilberts, and others, were able to reconcile their faith with their life stories. I also wish there had been more clips from a 1962 black-and-white Canadian documentary “The Eyes of Children,” offering rare candid glimpses inside the schools’ classrooms.

But it’s clear from what we see and hear that the survivors of these abominations want to move beyond their rage. They struggle valiantly with the truth of their pasts because they seek solace. When Ed says beseechingly to his estranged son, “Tell me what you want,” he is hoping, in his own halting way, to make amends. He tells Julian, “I didn’t leave you, son.” What he is really saying is clear: I am sorry. Know that you have always been with me.

The longed-for communion of father and son, which is also a legacy of this film, happens right before our eyes.

“Sugarcane” is rated R for some language.