China: Ethnic minority music finds an advocate

Laurent Jeanneau roams the ethnic minority villages of China recording the 'unofficial' music.

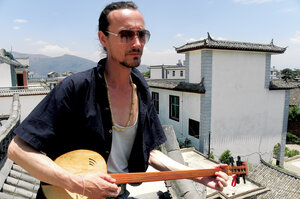

Laurent Jeanneau plays a dong pipa, a traditional Chinese instrument, on the roof of his home in Dali, China. Mr. Jeanneau travels across Southeast Asia to record ethnic minority singers and musicians.

Mike Ives

Dali, China

For the past decade, Laurent Jeanneau has roamed the villages of Southwest China and Southeast Asia, microphones in hand, waiting for chances to record the songs of ethnic minority singers and musicians.

If you visit the French expatriate in Dali, the touristy city in China's Yunnan Province where he lives, he will sell you one of the 80-odd albums he has recorded in ethnic minority villages and self-produced on Kink Gong, his home-grown record label.

Government officials in China and Southeast Asia have "bastardized" traditional folk arts under the banner of promoting ethnic diversity, Mr. Jeanneau charges, and the albums he sells to tourists are "acts of resistance" to state-directed cultural paradigms.

"When I look for music, my rule is, 'Look for the less obvious,' " Jeanneau said in English on a recent afternoon in Dali. "The cliché is the tip of the iceberg. I want to go underwater."

Jeanneau's grass-roots recording project, though unknown to most music fans in China and beyond, illustrates some of the nuances that accompany and impede attempts to document folk arts in a region where millions of ethnic minority vil-lagers still sing and play ancient – or at least ancient-sounding – melodies.

The project is a race against time, Jeanneau says, because it is increasingly difficult to find older singers and musicians who know and perform the traditional songs they learned as children.

In China, scholars say, the ruling Communist Party promotes hyperstylized – you might say kitschy – versions of the folk arts traditionally practiced by the country's 55 designated ethnic minority groups, or "nationalities," as they are called in Chinese.

The groups, which account for more than 8 percent of China's 1.3 billion people, include Tibetans and Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking Muslim group. Both Tibetans and Uighurs have staged recent protests in China, challenging the central government's authority.

China's Communist Party – which turned 90 on July 1 – cultivates ethnic performing arts as a way to "spread state propaganda" and make amends for "damage" inflicted on minority cultures during Mao Zedong's infamous Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and '70s, writes Helen Rees, an ethnomusicologist.

Dr. Rees, a professor at the University of California at Los Angeles who conducted fieldwork in Yunnan Province for her 2000 book, "Echoes of History: Naxi Music in Modern China," writes that state-sanctioned folk music in China smacks of what a foreign observer might call "domestic orientalism." China, she says, promotes ethnic minority artists as an "exotic alternative" to the Han, the ethnic group accounting for more than 90 percent of China's population.

Jeanneau says he is wary of government influences on traditional music in China and Southeast Asia. When he travels to villages in China, Vietnam, and Cambodia, he asks people to sing and play the tunes they would perform for each other, rather than for tourists.

Jeanneau "records real folk music," attests Stevan Harrell, an anthropologist at the University of Washington.

Since the 1950s, China's Communist Party has promoted music that, while technically "ethnic," emerges from ethnic minority musicians' perception of what the party thinks folk music "ought to be like," says Dr. Harrell, who has conducted fieldwork in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces and corresponded with Jeanneau by e-mail.

But Jeanneau's recordings, Harrell says, feature singers and musicians who, refreshingly, are not as influenced by party propaganda. Contemporary Chinese ethnomusicologists are attempting to record more authentically folksy music, Harrell says, but they "are not recording with as much breadth and dedication as Laurent."

Zhang Xing Rong, an ethnomusicology professor at the Yunnan Art Institute in Kunming, says that Jeanneau's recordings of ethnic minority musicians in southwest China are "superior" to the recordings that Mr. Zhang and his colleagues produce.

Jeanneau invests time living among ethnic minority villagers, Zhang says in an interview at his Kunming apartment. As a result, the Frenchman – who speaks fluent Chinese and Khmer – is present to record impromptu performances.

Chinese ethnomusicologists don't have as much time for fieldwork, "so we usually approach local officials and say, 'Hey, can you ask some of the better singers from around this area to come over and perform?' " recalls Zhang, who has documented ethnic minority music in Yunnan Province since 1984.

"What ends up happening is that we hear the local 'greatest hits,' " he says. "We're supposed to observe things objectively, but a lot of the music we record is removed from its context."

Jeanneau's recordings may challenge government-approved notions of folk music in China and Southeast Asia. But is the act of recording that music in its natural setting really, as Jeanneau contends, an "act of resistance" to the status quo?

Not exactly, says anthropologist Harrell. China's Soviet-influenced campaign to identify ethnic minorities, Harrell wrote in his 2001 book, "Ways of Being Ethnic in Southwest China," "is not a one-way thing, imposed top-down on passive local peoples," but rather a "two-way process of co-optation."

Many of the government officials who promote ethnic minority music in China are themselves members of ethnic minority communities, Harrell explains, and they celebrate their ethnic identity partly as a way of promoting "ethnic tourism."

Culturally diverse Yunnan, one of the provinces where Jeanneau has recorded performers, is an epicenter of China's ethnic-tourism industry.

Jeanneau acknowledges that his "resistance" to government-sanctioned performing arts is fraught with cultural nuances. He is not an "authority" on ethnic minority culture, he says, but rather a guy who likes to record talented musicians who naturally express their emotions in song.

"Singers who are trying to impress you too much are missing the point," he says. Jeanneau, whose scraggly ponytail conveys a bohemian vibe, is quick to distance himself from the Western scholars who also conduct fieldwork here.

"I'm not part of the university world," he insists, a little combatively. "I'm a totally independent person."

Western scholars are typically concerned with the ethical implications of their fieldwork. Asked whether he is similarly concerned, Jeanneau demurs: Being a foreigner in ethnic minority villages presents challenges and misunderstandings, he says, but his recordings benefit the communities he visits.

If he made more money selling his self-produced albums, Jeanneau says, he could afford to pay the performers more than five to 10 euros per session – a rate he says is comparable to that paid by university-funded scholars. Jeanneau himself lives modestly with his wife and son in a no-frills concrete home. He edits his recordings on a battered laptop computer.

Although he lives a hand-to-mouth existence, he vows he will never compromise the integrity of his albums by altering them to suit popular tastes.

"You might have a few crying children, and chickens, and bugs from the jungle in there," he says. "But that's the way I capture sounds."