How basketry preserved a people

Zulu basketry began to die out because of tin and plastic containers, but now the craft is flourishing.

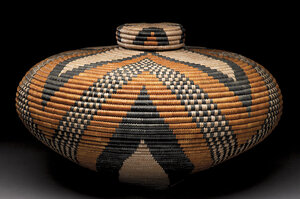

‘Lidded Basket’ by Beauty Ngxongo (10 by 18 inches, fibers, 2005). Decades ago, a neighbor taught Ms. Ngxongo how to make these traditional Zulu watertight containers. Now her work is shown in museums worldwide.

Courtesy of the Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art

Beauty Ngxongo's basket is a domestic object shaped to hold liquids, but it also holds a community's traditions. Ms. Ngxongo is the most renowned Zulu basket weaver alive. Her work is in New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, major South African museums, and Washington's Smithsonian Institution.

The story of Zulu basketry is one of revival. The craft was dying because of the introduction of tin and plastic containers. A Swedish minister, Kjell Lofroth, and his wife, Bertha, witnessed the decline in local crafts. When drought struck in the late 1960s and people in the rural KwaZulu-Natal Province faced starvation, Mr. Lofroth began the Vukani ("Wake up and get going") Arts Association to help single women support their families. Only three elderly women knew how to make baskets, but they taught others. A market, and the craft, flourished.

As a child, Ngxongo wove doormats and table mats. About 30 years ago a neighbor taught her how to make elaborate, geometrically patterned baskets from grasses and palm leaves dyed with berries, roots, and bark. Hand-stitched with 180 to 300 stitches per square inch, the watertight baskets can take months to make.

Ngxongo now employs 13 women to make the grass calabashes. Sadly, her village north of Durban is the epicenter of HIV/AIDS. She has lost many friends and family members.

"It's a sad story, but it's also a story of empowerment and triumph," says Susan Cooksey, curator of African art at the Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida in Gainesville. "Beauty is a survivor and a champion," she adds. "That makes [what she creates] more than just a beautiful work of art. There's a lot of love in there, and spiritual strength."